A Playbook for Playful Publishing, Part I

The Promises and Trappings of BookTok

Hi there! I’m Maxime, and you’re reading Recreations, a newsletter about the intersection of media, technology, and culture.

You’re receiving this either because you subscribed or because someone forwarded it to you. If you’re in the latter camp, you can subscribe here or via the button below.

If you know anything about me, you might know I love reading. I read fiction and non-fiction, big books and small books, and authors living and dead. A few months ago, I set out to better understand the industry behind the books. Today, I’m excited to share my findings.

Let’s get it out of the way: book publishing is in a weird state right now.

In the past few years, publishers have directed all their efforts toward courting TikTok, its community, and its algorithm. On the surface, they have been rewarded handsomely for it. Sales are booming and younger generations are reading again after decades of attrition.

But there is a flip side. In the process, the industry has given away any semblance of control over the customer journey and exposed itself to a single point of failure — a risky position to be in. In this series, I want to explore how and why publishers found themselves in this predicament, and what they can do to regain control of their destinies.

This here is Part I: The Promises and Trappings of BookTok, where I unpack BookTok’s workings, why the platform might have looked so appealing to publishers when it emerged, and why its ever-growing influence actually threatens the industry’s long-term prospects.

Here’s what’s in store for the coming weeks:

Part II: On Judging Books (and Publishers) by Their Covers will explore exactly why we care about a book’s cover so much, what messages it sends and to what purpose, and why its pull has never been stronger.

Part III: The Playbook will lay out five strategies that publishers can explore to generate engagement and revenue, and to grow awareness beyond individual IP and toward their own brands. And finally,

Part IV: Monsieur Toussaint Louverture: Publishing as Craft will be a deep dive into Monsieur Toussaint Louverture, a French publisher whose opinionated curation and attention to detail represent the best of what indie publishing can be.

If you haven’t already, make sure to subscribe so you get every installment straight into your inbox.

I hope you’ll enjoy the journey.

Taking Stock of BookTok

If you don’t know already, “BookTok” is the portmanteau used to describe a corner of TikTok dedicated to everything books and reading. There, millions of fans — predominantly teenagers and young women — share book-related opinions, rankings, recommendations, and rants under the hashtag #BookTok, with a variety of complementary hashtags providing ever more granularity for those browsing the platform with specific cravings.

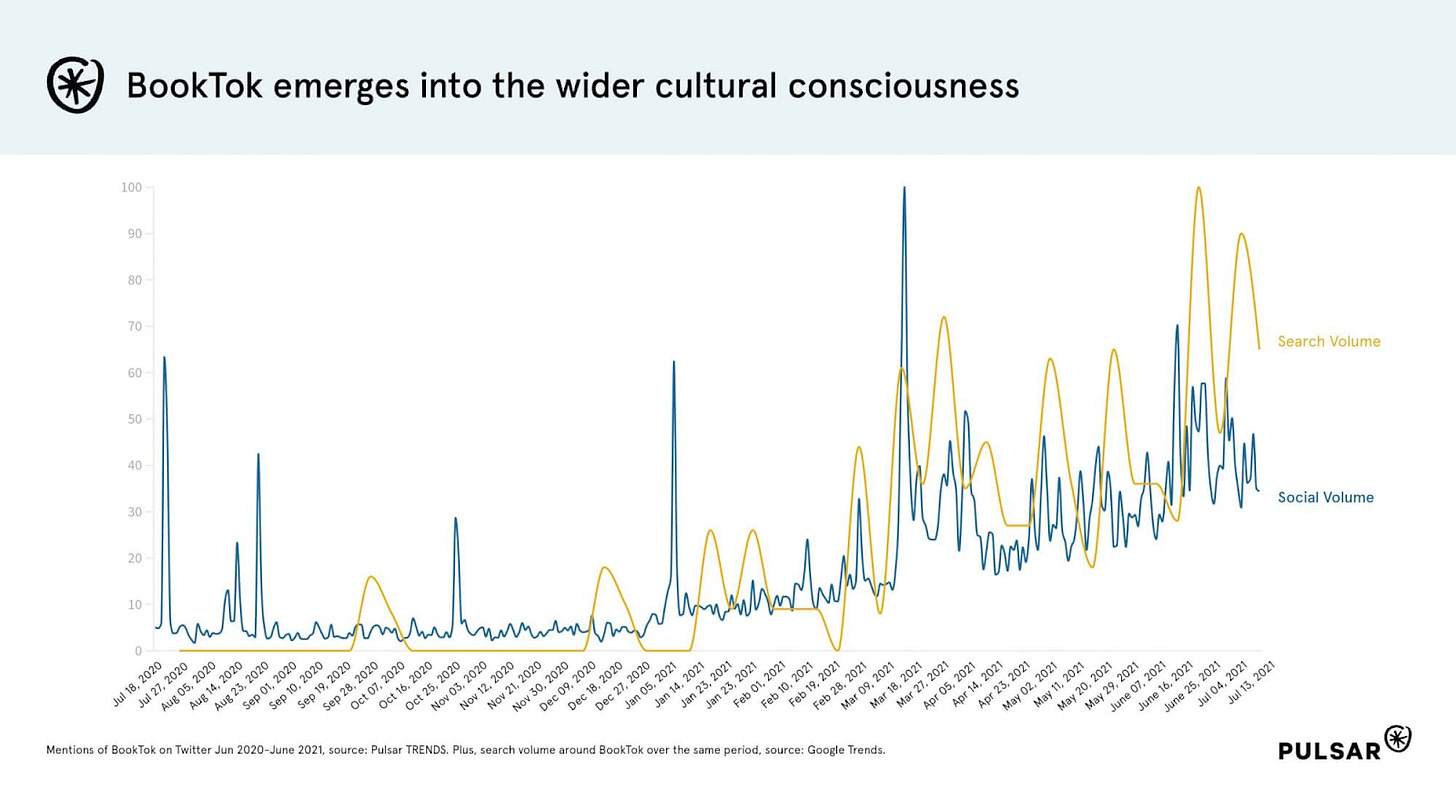

The size and reach of this community are hard to overstate. BookTok emerged seemingly out of nowhere around the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when millions of people stuck at home turned to reading (and reading-related content) for entertainment. Since then, it has seen continued growth. In July 2023, videos with the #BookTok hashtag had been viewed more than 91 billion times, up from nearly 60 billion views the year before, and only half that in 2020. At the time of writing this, the hashtag has reached well over 200 billion views. BookTok videos have grown by nearly 15% in the first nine months of this year compared to 2023.

TikTok is not the first social platform to attract readers; both BookTube and Bookstagram have been lively communities for years. Last year, an account that goes by Bigolas Dickolas on X (still Twitter at the time) made the rounds for enthusiastically promoting a sci-fi novella from 2019, turning it into an Amazon bestseller overnight. But together, TikTok's scale, social features such as Duets and Challenges, and inescapably perceptive algorithm have given BookTok the kind of visibility that none of its predecessors ever had.

Its impact has spilled over from inside the app and into the physical world. More than 100 authors with large BookTok followings drove $760 million in sales in 2022, a 60% increase from 2021. Sales of romance, thrillers, and young adult novels, all three BookTok favorites, have largely outperformed the overall market. Groups of teenagers who met on BookTok now have bookshop days out, after which they'll go back to the app to tell others about their hauls — a perfect loop from digital to physical to digital again.

Professionals across the industry have rushed to adapt their practices to this new, social-driven reality.

It starts at the very top of the value chain, with rights acquisition. Traditionally, readers learned about new authors from booksellers in a top-down fashion. Now, it’s the publishers who are learning about viral authors from retailers, who come to them with requests from readers, or from lurking on the platform themselves to see which names are trending. Titles whose sales had been flat for years are routinely propelled to bestseller lists after being rediscovered on the platform. With online chatter and virality serving as proxies for reader demand, even backlist titles are up for grabs. In October 2022, Orion Fiction acquired the rights to Jessa Hasting’s romance series Magnolia Parks, whose first three books had already been self-published, in a six figures deal.

Promotion has been similarly disrupted. Because having a social presence can significantly boost sales, many publishers now prioritize authors with a platform they’ll be able to use to kickstart a book's marketing. Meanwhile, self-published authors are being courted by a growing number of BookTok-focused creative agencies and, of course, AI-enabled tools that claim to make them video-ready.

Finally, there's distribution. Brick-and-mortar booksellers now curate dedicated displays featuring books that are popular on the app. At large chains, inventory management, always a hazardous task, now needs to align not just with seasonal peaks but with BookTok-induced surges in demand. Booksellers including Barnes & Nobles, Books-A-Million, and Canada's Indigo Books & Music have all added BookTok categories on their websites to guide online shoppers. Wherever you look, BookTok — what the community wants, and how to deliver it — is now the single biggest motivation behind the industry’s every move.

Smiling In the Face of Disruption

Why were publishers so eager to onboard BookTok? I think the rationale can be boiled down to two reasons. First, the platform represented an opportunity to directly — or so they thought— engage with readers, a major shift from the state of affairs. Second, BookTok's community happened to consist mainly of younger, notoriously elusive, demographics. Let’s see why these promises may have sounded so compelling.

Direct Connection

The notion that publishers should be talking to their readers will sound familiar to most of you. In tech, collecting user feedback has long been a core operating principle when it comes to testing hypotheses, identifying unmet needs, and more generally improving products and services. The tighter the feedback loop, the better.

Meanwhile, the publishing industry still operates under very different rules. The reasons for this are as much structural as creative.

On the structural side, it's important to note that publishing is really a B2B business: publishers sell not to readers, but to bookstores, retailers, libraries, academia, and more. To do so, they rely on intermediaries — namely, wholesalers and distributors — who acquire books from them and sell them to the rest of the industry. Wholesalers and distributors differ in several aspects. For example, the former work with publishers on a non-exclusive basis, the latter on an exclusive basis. One buys books from publishers at a discount off of the list price, sells them to physical and online retailers at a smaller discount, and pockets the difference. The other charges a percentage of net sales and provides publishers with additional services including sales, marketing, and data cataloging. Despite these nuances, however, both play the same key role in the value chain, enabling customer-facing businesses to buy, and, crucially, return books in large quantities instead of transacting with thousands of different publishing houses. Commercially, this makes publishers not just once but twice removed from actual readers.

This intermediation has serious consequences.

The first one is on brand awareness. On the one hand, publishers tend to focus only on "direct response" marketing as a way to drive sales for individual titles, as opposed to brand marketing, which aims to increase overall brand awareness. This is sensible, considering that they are indeed in the business of selling books; with competition high and margins low, chasing brand equity for its own sake may seem like a frivolous endeavor. But this negligence also means that readers remain largely indifferent to whichever publisher might be behind their next picks. Their focus is on the book; their loyalty, to the author. Safe for a select few names, most of us would be hard-pressed to say what it is that a particular publisher stands for.

The second consequence is on engagement and monetization. To borrow from tech parlance, publishers have no control over consumers' discovery and purchase experience; that stage of the journey is in the hands of the retailers. With no direct view of readers' contact info and preferences, no entry point into their wallets, publishers have no way to re-engage even their most avid readers or to complement their legacy B2B models. For example, it's telling that most experiments around subscription boxes have come from startups — in other words, outsiders — rather than from publishers. Likewise, merchandising today is the prerogative of only a handful of publishers fortunate enough to have a strong brand (e.g. Penguin), strong IP (e.g. Bloomsbury, of Harry Potter fame), or some combination of both.

On the creative side too, the relationship with readers is tenuous at best. Due to the medium's nature — a self-contained, definitive product —, communication is, by default, awfully sparse. It can be years before an author publishes their next novel, or even in between two installments of an ongoing series, and any progress is usually kept secret until completion. While the most digital-savvy authors today might share more regular updates or spontaneously comment on a fan's video, the connections they forge doing so are theirs and theirs alone. Publishers, again, remain largely invisible, and benefit only indirectly and further down the line, through book sales.

For the industry, BookTok appeared to be a credible solution to these problems. A chance to bridge the gap: to finally engage readers unmediated, grow brand equity, and set foundations for more direct monetization.

Fountain of Youth

The lure wasn't just any readers, though. Crucially, TikTok's user and creator base skewed young, and BookTok reflected, and continues to reflect, that fact. Here was an opportunity, publishers hoped, to engage, educate, and influence the next generation of readers.

It was not a trivial matter. Reading has seen a marked decline among younger demographics in recent years. In Australia, the portion of children aged five to 14 who read in their spare time fell by more than 6% between 2018 and 2022. In the UK, only 26% of under-18s spent some time reading each day in 2019, the lowest level since the charity's first survey in 2005. In France, the share of people who identified as readers among those aged 15-24 decreased by 12 percentage points between 2019 and 2022. Attrition is rarely good for business, but it's especially alarming when it's affecting those you thought you'd be selling to next.

The irony, of course, is that TikTok was very much part of the problem. An inconvenient truth about why people don't read is that, quite simply, they'd rather be doing something else. These days, that “something” usually takes place in front of a screen. Social media and gaming have been noticeably eating up kids' and teenagers' leisure time and good ol' reading has been getting the shorter end of the stick. This encroachment isn't just metaphorical. A study conducted in France in 2022 found that 47% of young readers often do other things while reading, with 37% stopping to text friends, 27% scrolling social media, and 25% watching videos. Screens are, literally, displacing books in people's hands.

Facing those facts, publishers were stuck between a rock and a hard place. They could either do nothing and watch their readership age out and their prestige and business erode, or enter enemy territory and hope to turn digital to their advantage. As the saying goes, "If you can't beat them..."

Roughly four years after BookTok started its ascent, its sway over young readers appears stronger than ever. In a poll conducted by the U.S. Publishers Association in October 2022, 59% of 16–25-year-olds said that BookTok or book influencers had helped them discover a passion for reading; more than half (55%) said they turn to BookTok for recommendations; and 68% said BookTok had inspired them to read a book that they would have never considered otherwise. It's no small paradox that the same screens that have been hijacking people's attention for years are also what's driving reading's (relative) resurgence. At this point, BookTok looks inescapable.

The Boiling Frog Problem

By and large, the industry has welcomed the change — record-breaking sales tend to make everyone cooperative. But caution is warranted.

To begin with, BookTok-induced growth is not all “up and to the right". After a virtually uninterrupted rise during COVID 19, it was only logical that the platform would start showing some variability. In July last year, sales from the roughly 180 authors Nielsen's BookScan tracker follows on the platform actually fell by 4.5% compared to 2022. Sales for the Young Adult category, normally a significant growth driver, were down 1% after increasing 4% between July 2021 and 2022. Though BookTok is nowhere near done, publishers should prepare themselves for when the momentum ends.

It's also clear not everyone is benefitting equally. For better or worse, success on BookTok is self-reinforcing: the more popular an author appears to be on the platform, the more users are incentivized to post about them to rake in more views and followers. In turn, the algorithm learns to favor the same content over time, pushing the same few names to more and more viewers. In July 2022, videos featuring the hashtags #ColleenHoover, #ColleenHooverBooks, and #CoHo had nearly 2 billion views combined, a level of ubiquity that makes Hoover virtually undethronable. According to Circana BookScan, in 2024 so far, print sales for authors with large audiences on BookTok have seen a 23% (!) increase compared to last year. By comparaison, in the total adult fiction market, print sales are up only 6% over last year. As BookScan analyst Kristen McLean put it, the community "is becoming less efficient or engaged in surfacing new authors overall."

Admittedly, both of these points are manageable. Slower growth is still growth, and publishers still have many levers they can pull to squeeze sales out of the platform. Meanwhile, whatever hierarchy is taking form on BookTok between established authors and newcomers always existed offline; TikTok's digital environment and social features are only amplifying it.

More insidious, and dangerous, is platform risk. As publishers and booksellers continue to lean on BookTok for everything from market research to discovery, promotion, and sales, they are giving away any semblance of control over the customer journey. Even worse, they are exposing themselves — both individually and collectively — to a single point of failure, a risky position to be in no matter the industry.

Commoditization Engine

As it stands, BookTok is a commoditization engine.

Because the community tends to reject any overtly polished marketing, publishers can't directly steer readers toward their catalogs — influence has to be mediated. Today, this is done mainly by tapping influencers that can kickstart traction before organic interest hopefully kicks in. But this practice is problematic for several reasons.

First, this kind of fragmentation can blur a publisher's intended message, as influencers will each be presenting the same book to their respective audiences in their own, unique ways. This comes in stark contrast with the tightly controlled marketing material that publishers would normally be sharing with retailers in a traditional model.

The second reason is fairly unique to books as a category. Some products, like cars or make-up, call for at least some degree of brand loyalty. A beauty influencer, for instance, will usually abstain from jumping from one brand partnership to the next if they want their audience to see these deals as anything else than cash grabs. On the other hand, nobody expects a book influencer to work exclusively with one publisher, no matter how much they enjoy their editorial stance. In fact, when it comes to reading, repeat purchases and eclecticism are not just accepted but praised in ways that they are not in other product categories.

This leniency has been a boon to bookfluencers, some of whom are currently promoting almost one book a week. But since the same influencer could be partnering alternatively (and indifferently) with multiple publishers, the marginal value of each sponsored post tends to only decrease over time. Publishers are therefore left with two options: either work with the same prominent influencers as their competitors and be commoditized as yet another sponsor; or move down the food chain to less courted micro- and nano-influencers, whose impact on sales might not be as great. Not an easy call!

To make things even more difficult, commoditization also plays out at the interface level. In the good ol' Instagram days, brands and content producers could at least use the grid as a canvas for editorialization. With TikTok's feed-centric UI, designing with a clean, static view in mind no longer makes sense. This makes visually conveying what you're about much harder. Today, a publisher's "identity" on BookTok really only consists of whatever users are saying about its books.

TikTok’s Book Strategy

To make matters worse, TikTok has been slowly but surely encroaching on the publishing value chain, integrating more and more touchpoints under its brand and interface.

In July 2022, the company partnered with Barnes & Noble on "an all-new, interactive summer reading experience" that bridged in-app engagement and in-store shopping through a time-limited Challenge and a dedicated social hub. In November, it onboarded partners including HarperCollins UK, Bloomsbury and Bookshop.org to launch a new Books category on TikTok Shop in the UK, enabling users to buy books without leaving the app. Finally, in May last year, the company held its inaugural Book Awards for the UK and Ireland, which encouraged the community to vote for the winning books, authors and creators — again, in-app.

Across these initiatives, a pattern emerges. Firstly, TikTok has made sure to work hand in hand with established players, from publishers to online marketplaces to festivals, in an attempt to show goodwill and position itself as an enhancer to the industry. Secondly, these actions strategically leverage its community's involvement: the more engagement TikTok generates around books — whether that's in content, votes, or sales — the better it can convince future partners to place their trust in its platform.

Behind the scenes, however, the goal isn't just collaboration: like it has in music, TikTok is trying to capture as much of publishing’s value chain as possible. In March, TikTok's parent company ByteDance filed a trademark with the US Patent and Trademark Office for 8th Note Press, describing it as a company that will provide a range of publishing products and services including print, ebooks, and audiobooks. According to the application, the new venture will also be home to "virtual communities that allow registered users to participate in discussions, consumer reviews, and social networking."

While ByteDance insists that 8th Note is a separate entity from TikTok, the synergies are obvious. Katherine Pelz, who was appointed as 8th Note's first acquisition editor, specializes in romance, BookTok's favorite genre. (Pelz has since moved to a similar position at CooTek.) Along with an advance and royalties, pitches to authors have mentioned social media campaigns, a variety of marketing for which TikTok would be the obvious option. In July last year, the New York Times reported that the new company would expand into physical books once TikTok had launched its much anticipated online retail platform, TikTok Shop — which debuted in September 2023. These plans are now near completion: last month, 8th Note Press announced it is teaming up with Zando on a new joint imprint that will release 10 to 15 books a year, with the first titles arriving in early 2025.

All these moves have, understandably, raised alarm. Some in the industry fear that ByteDance could favor its own books on BookTok, forcing others to pay up in order to reach viewers. What's more, given the black box nature of TikTok's algorithms, traditional publishers and self-published authors would have no way to prove wrongdoing. Another concern is that ByteDance could use TikTok's immense trove of data to pick up early signals about trending genres, tropes, and authors. This much has been all but confirmed, with Jacob Bronstein, the head of editorial and marketing at the company, revealing that 8th Note is “‘building backwards’ by acquiring books that feed into those trends and conversations.’ This would give 8th Note a headstart over its less technologically-savvy competitors to buy up rights, or even develop demand-driven books internally.

The Many Flavors of Platform Risk

While some of these concerns might look overblown for now, platform risk isn't to be taken lightly. The history of media is littered with examples of companies, and even entire industries, too eager to rely on an uncertain third-party, only for their own businesses to crumble when the rug was pulled from under them.

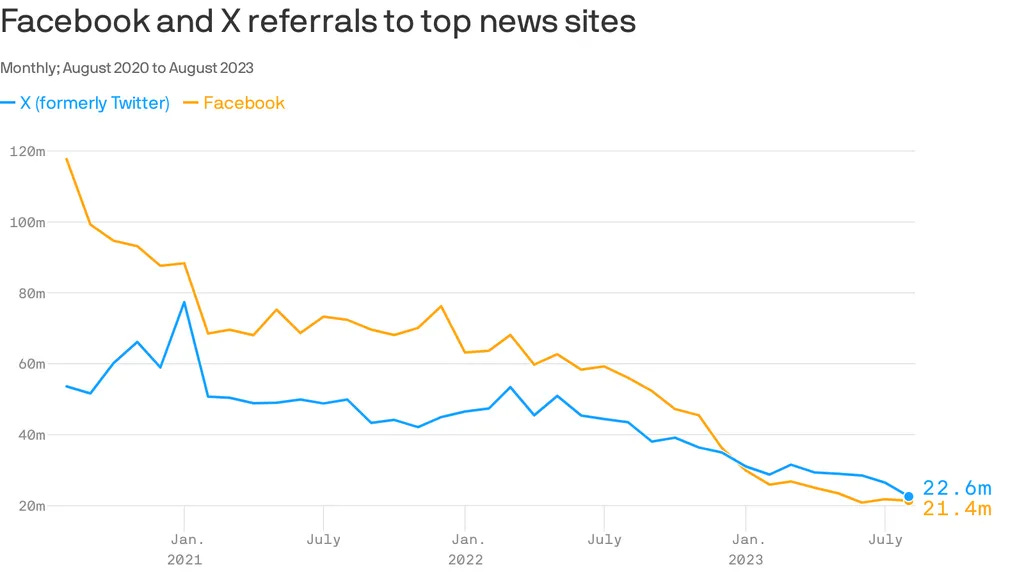

Consider the now infamous "pivot to video," the rushed adoption of video content as the new default by digital publishers in the mid 2010s. After Facebook in 2015 shared data claiming that users overwhelmingly preferred video over text, the then fast-growing army of social-first publications including Buzzfeed, NowThis, and Mashable shifted their focus overnight, laying off writers and editors in droves in favor of "snackable" video content supposed to better attract advertisers' money. When it turned out one year later that Facebook had been seriously (and knowingly) inflating key usage metrics for years and consumer demand for the medium just wasn't there, the damage was done and publishers went into disarray.

Recent history has had its share of trickery too. In February last year, TikTok ran a month-long test in Australia that limited the amount of licensed music some users could encounter on the platform. Understandably, many in the industry blamed the company for trying to downplay the significance of music on its platform. Though TikTok denied it being a negotiation tactic, Billboard noted that "the company [was] gathering data during a year when most, if not all, of [its] agreements with music rights owners [was coming] up for renewal." Though TikTok ultimately walked back this initiative, the experiment had a chilling effect.

What is clear from these examples is that platform risk comes in many shapes and forms. Neither in the "pivot to video" debacle nor in TikTok's sound-off test did the underlying platform need to actually shut down for it to impact the businesses building on top. In the first case, an entire industry wasted millions and affected hundreds of livelihoods chasing engagement based on false promises. In the second, a technology platform was able to single-handedly suppress rights holders for a month just to test a business hypothesis. Small(ish) decisions, big consequences.

Trouble could also come from elsewhere. For example, TikTok's ties with China through its parent company make it especially susceptible to regulatory scrutiny. Though the company has so far managed to avoid a formal ban in the U.S., it's already been blacklisted by dozens of countries and government bodies over privacy and security concerns. Top-down intervention such as these can abruptly and irreversibly disrupt entire ecosystems. With all the business that's at stake, are publishers prepared for such extreme scenarios?

The Writing on the Wall

On paper (pun intended), BookTok’s rise has been a boon for the publishing industry. It has breathed new life into reading, sparking younger generations’ excitement for the written word after years of indifference and boosting sales across both new and dormant IP.

But the platform's influence should raise serious concerns. The “pivot to video” debacle and the news industry’s continued struggles with social platforms offer cautionary tales for those that subject themselves to the whims of a single, opaque intermediary. Books may have TikTok’s attention for now, but what happens when they no longer do? Or when the company really starts gunning for more of the value chain? The more publishers scramble to capitalize on BookTok’s momentum, the more they expose themselves to platform risk, with potentially ruinous consequences.

Ultimately, the industry's naive embrace of BookTok reveals deeper issues. Structurally dependent on intermediaries to reach consumers, almost indistinguishable behind even world-famous IP, and faced with the relentless competition of screen-based entertainment, book publishers have, understandably, been desperate for anything that might rejuvenate their business. Even at the cost of their long-term resilience and independence.

Spray-and-praying on BookTok can’t possibly be the solution to these problems; publishers need to learn how to stand on their own. This means strengthening their brands beyond one-and-off releases, cultivating a diverse array of discovery, engagement, and monetization channels, and overall bringing back a sense of experimentation and playfulness to their age-old trade. Only then can they hope to weather the storms that lie ahead.

That’s it for Part I! In Part II next week, we’ll explore why we care about a book’s cover so much, what messages it sends and to what purpose, and why its pull has never been stronger.

Thank you for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this essay, please consider giving it a like and take a minute to share it with others. It really helps.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts! You can find me on X, or just reply to this email.

Thanks to Jimmy for reviewing a draft of this piece.

Finally a new post! 🎉