Ready-made aesthetics

On scaling creative work, from the atelier to the internet

Hi there! I’m Maxime, and you’re reading Recreations, a newsletter about the intersection of media, technology, and culture.

If you’re new to this newsletter, you can subscribe here.

How creativity became scalable

Painted in broad strokes, the history of art has seen a continuous move towards more replicable, more scalable, and more shareable forms of creativity.

At the technical level, a combination of scientific innovation and creative drive gave birth to techniques like printmaking and photography that allowed artists to accurately reproduce their work from a single point of reference. The mold and the lithographic stone, the engraved metal plate and the negative each became vessels in which artists could imprint their vision. With new tools and processes, art became replicable.

There were complaints along the way — art has its Luddites, too. Charles Baudelaire in his Salons feared the impact of photography, calling the new medium "the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies." In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin similarly lamented over the irremediable loss of the aura — the unique aesthetic authority of an artwork. Critics would systematically pit replicability against originality, painting it as an attribute of lazyness and decadence.

But culture did catch up with technology eventually. Time, and the combined efforts of the artists who dared to experiment with these techniques in spite of intimidation, slowly but surely legitimized these media, granting them a place of their own inside the artistic canon. Though age-old cultural hierarchies have inevitably persisted between art forms, the sheer time and sweat that go into creative production no longer determine the value of an artpiece.

How we define and reward creative work acknowledges this shift. Authorship today extends far beyond an artist's personal efforts; in fact, many of the most revered artists were sometimes barely involved at all after the ideation phase. Rodin's work stopped with clay, with all later stages being handled by trusted craftspeople. Warhol's "piss paintings" — canvases prepared with copper paint that was then oxidized with urine — were sometimes made by "ghost pissers." In more recent times, most of Damien Hirst's "spot paintings" have actually been produced by his assistants — technically speaking, only the instructions are his.

For artists, this technical, cultural, and legal decoupling of their time and work was a blessing, enabling them to produce more and reap the benefits (both financial and reputational) far and wide. Their work was able to reach more viewers and collectors, in more places, and to do so more quickly. Technical replicability at the service of artistic singularity.

Productized worldviews

Fast forward to today, and to the ever-growing Creator Economy.

Low to zero marginal costs in the creation and distribution of digital goods have enabled millions of people to find an audience and monetize their work. From ebooks to songs to digital art, every form of creative production can, in theory, reach consumers globally.

But the change is even more profound. The internet enables creators to distribute not just their work, but their vision, too. To share with others the way they see and hear, at scale - to productize their worldview. The resulting product then is no longer a finished good, but rather a toolkit that consumers can play with and integrate into their own workflows.

A great example of this can be found in the surprising realm of photography presets.

Presets are software adjustments that alter a picture or video's appearance by fine-tuning metrics like lighting, color, and contrast. Think of them as ready-made aesthetics, a convenient way to give your creations a desired look and feel. Whether for action shots, still lives, or portraits, there's bound to be a preset out there that can help you bring the best out of your visual work.

Presets therefore have substantial value — especially to beginners, who haven't yet mastered the intricacies of editing and may be willing to shell out a few bucks to speed up the process. More than a creative shortcut, though, they're a learning tool: because all the minute adjustements are exposed in the software, you can see exactly how a given look was achieved and learn how to recreate it on your own. Every slider and button gives away part of a larger secret.

Accordingly, an increasing number of creators have started packaging them into standalone digital products, leveraging platforms like Gumroad or Sellfy for distribution. Here's an extract from the product page for "HIPSTER AF," a preset collection from photographer Sorelle Amore:

If you’ve ever looked at my photos and wondered how I edit them, wanted to copy my editing style, or just needed some sweet Lightroom presets to give all your photos that extra moody vibe, I’m very happy to present to you all 17 super sexy presets that I use on almost all of the photos you see on my own Instagram.

In this inconspicuous blurb, Amore aptly unpacks the different reasons why someone might want to buy the product as the following:

learning ("wondered how I edit them");

imitation ("wanted to copy my editing style");

convenience ("just needed some sweet Lightroom presets")

In that view, her primary work on Instagram can be seen as a showcase of her skills, a glimpse of something more: it's what sparks interest and, ultimately, buying intent. The presets, however, are the aesthetic enabler. Through them, Amore's creativity becomes available for others not just to consume, but to aspire to. Achievable - for a price.

Artist-driven products

Amore's case is just one of many, as creators big and small can now productize their aesthetics and turn them into hard cash, at scale.

This has become a valuable trend to tap into for innovative companies out there. What if you could somehow aggregate supply to draw the respective audiences of individual creators to artist-driven products? Strategically work with artists on tools that reflect their creative process and vision, and make it all accessible to the people that most want to learn from them?

As it happens, the music space already offers two such examples.

Leading the way is Spitfire Audio, a British music technology company producing high quality virtual instruments and sample libraries for the world's most demanding composers. As I wrote in my primer about the company:

Spitfire releases not just artist-focused content but artist-driven products, too, working with the best composers to release libraries of their sounds - it has six of Hans Zimmer alone. The producers who get these packs aren't buying a bunch of sounds, really: they're buying into an artist's vision. They're using these sounds as a way to instil a little bit of that artist's talent and unique touch into their own work. With these packs, inspiration becomes aspiration.

For example, the Hans Zimmer Percussion pack captures "the highest quality recordings, featuring the same players in The Hall at AIR Studios where Hans records his biggest scores, all mixed and produced by the man himself." In other words, you have access to the exact same material the master would use — it's as if he were peeking over your shoulder as you're creating.

Following a similar strategy is Splice, an online marketplace for sound packs and music production plugins and software. In December 2018, the company debuted Splice Originals, "Splice-produced recording sessions and sample collections from acclaimed musicians with unique perspectives."

Like the rest of the Splice library, Splice Originals include vocals, instrumentals, and live sounds. What's different about them, however, is that their content draws its value as much from the names behind it as from its strictly sonic qualities. Each sound pack explicitly names its influences and revels in metaphors that promise a world of possibilities.

Both Spitfire Audio and Splice point to the same trend, one where fans have access to the same creative capabilities as the artists they admire.

Today, any producer with internet access can choose from hundreds or thousands of sound packs, many of them available for free. To opt for a paid, artist-driven pack instead is a very deliberate act: it means you're hoping that it encapsulates a little bit of that artist's flair. You're collecting the digital bits of brilliance that will let you use "that sound" too. Doing so takes you that much closer to the creative process, compared to merely consuming that artist's work in its final form.

The Diminishing Marginal Value of Aesthetics

From a consumer's perspective, ready-made aesthetics make perfect sense — as Amore suggests, these products allow for learning, imitation, and convenience. As more people try their luck as creators and they, too, need to blow their followers away, we'll see many of them take from the work of more established artists.

From an artist's perspective, however, it takes confidence — audacity, even — to give others the technical ability to copy your best work. After all, if earning consumers' attention is a zero-sum game, creators would have every reason to protect their secrets from current and potential competitors. With a scarcity-driven mindset, your ideas and vision might be the most precious thing you have. So why are artists giving away what makes them unique, and what does that tell us about the state of creation?

In his essay titled "The Diminishing Marginal Value of Aesthetics," Toby Shorin argued that creatives can no longer realistically rely on the uniqueness of their aesthetics to thrive in a crowded marketplace.

The "falling cost of aesthetic production" (thanks to "cheap and efficient tooling") and distribution (thanks to dense social networks and financial incentives) has made it easy - and worthwhile - for anyone to copy a creator's aesthetic. Shorin writes:

Cheap to produce, free to distribute, yet still impossible to meaningfully automate, aesthetic production is an increasingly precarious vocation. The status associated with aesthetic novelty is eroding, and novelty itself has become difficult to eke out of a system in which everything is visible, accessible, and relativized. The graphic design profession is being strangled in a race to the bottom of the market, and the distributed network topology of the internet is largely responsible; aesthetics has, simply put, been disrupted.

This discrepancy between how much time and effort it takes to come up with a novel aesthetic and how little time and effort it takes for someone else to copy it thus makes aesthetic innovation decreasingly appealing. Seeing a somewhat undervalued aesthetic, aesthetic grifters can simply claim it as their own and use it to reach their own goals. Imitators are too many to fend off for long, and a creator only has so much time, or willpower, to do it anyway.

In that sense, increasing productization is both a consequence of, and a possible solution to, the diminishing marginal value of aesthetics.

A consequence, because as aesthetics lose their defensibility, creators are forced to either come up with new ones at a faster pace to stay culturally relevant (i.e. industrialize creativity), or drift in the fray as now undifferentiated producers (i.e. become commoditized). As Shorin points out, this has direct economical consequences: only with original work can creatives command a premium in the marketplace. Without it, their competitive margin all but disappears, and they're left executing on somebody else's ideas.

And a solution, because productizing themselves paradoxically allows artists to reclaim part of their cultural influence. As opposed to letting their aesthetics circulate unchecked across platforms, shamelessly picked up and imitated by others, turning their worldview into software tools offers at least a semblance of control. If your style is bound to be copied into ubiquity, you might as well extract some value from it along the way.

Looking ahead

If Amore, Spitfire, and Splice are any indication, every piece of creative software, from Lightroom to Ableton, could soon see artists productize their workflows and worldviews.

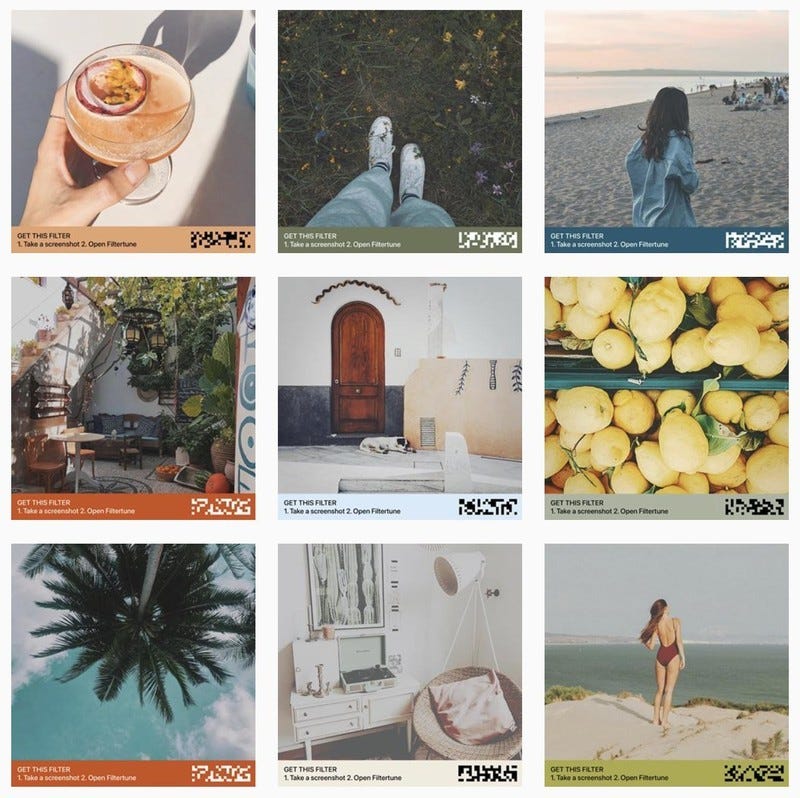

Freelance filmmaker Ezra Klein monetizes such assets as film grain overlays and text animation presets. Design studio BLKMARKET sells wood and chrome texture PNG packs. Filtertune, an app developed by mobile creativity unicorn Lightricks, lets creators design their own personalized preset photos filters and share them across social media as photos with a special QR code attached. In time, every medium will see this sort of productization take off.

From there, opportunities abound. Let's work through a few of them.

DIY educational bundles

To be sure, curiosity wasn't born with the internet. But it was certainly enhanced by it, offered new and faster ways to access knowledge in every field you could ever think of.

On TikTok, educational content repeatedly reaches the top of the platform across categories, from cooking to plant care to beekeeping. Videos with the hashtag #howto have collectively amassed over 9 billion views to date, making the platform a force to be reckoned with in the future of peer-to-peer education.

Growing interest in the creative process offers exciting opportunities for a new kind of educational bundle. Creators could package assets they use in their preferred medium — photos, audio stems, or video clips — together with a handbook or full-fledged course showcasing their thought process and workflow. Selling samples on Splice? How did you achieve that signature sound? Selling photo presets on Gumroad? What slider did you tweak to come up with that particular look and feel?

Providing access not just to the what (the finished product) but to the how (the source material and process), too, would spark a new sense of appreciation for the craft that goes into any kind of creative work, and strengthen the connection between creators and their fans.

Artist-driven software experiences

Handbooks and courses are but a first step. Next, I think we'll see creative tool companies partner with artists to let them take control of the user experience at the software layer — what Tina He last year described as Embedded education:

Embedded education is the practice of educating people through encounters that they already have with systems that exist primarily for non-educational purposes. While the recently popular concept of “embedded finance” distributes financial products at the point of digital transaction, which is the most natural way for consumers to discover options, embedded education delivers learning at the point of getting the job done. From content delivery all the way to community engagement, Embedded Education is an evolution from progressive learning, which follows clear logical steps to intuitive learning, which relies less on the route memory of disparate knowledge nodes, but on the relationship between these nodes.

In the world of enterprise software, WalkMe has done wonders to provide professionals with in-app guidance. By laying contextual calls-to-action and walkthroughs over complex interfaces, the company's solutions increase usability and improve users' onboarding, training, and overall satisfaction with the software they use on a daily basis.

Now, there's an opportunity to do the same in the consumer space.

Imagine having access not just to a creator's filters, presets, or sounds, but also to the "how" and "why" of their creative process, right from your creative software suite — think KHSMR showing you how to use his Splice plugin, or Timbaland teaching you his favorite Ableton tricks. A step-by-step audio or video commentary, enriched with overlays, would guide you through the experience, bringing the product's educational potential to a whole new level. Embedding their insights into digital packages could allow artists to scale their vision even further.

Creative LEGOs

We're entering somewhat more experimental territory, but one I'm excited to watch develop over the coming months and years.

By now, you've probably heard of Web3 - the decentralized internet building on open protocols and enabled by technologies like the blockchain. (I won't get too much into the details here. Others have done it before, and better than I ever could). If Web2 is the internet we know and use today, Web3 could be its next iteration.

Of Web3's many attributes, three seem of particular relevance to the matter of creative work: composability, provenance, and smart contracts. To understand why, let's first see what they're about.

Composability is the ability to assemble disparate building blocks to develop one's own custom technology stack, using open source code. The result are highly modular solutions that can take the best of existing protocols to come up with faster, more intuitive, or/and more capital-efficient offerings.

Provenance is the historical record of ownership of a digital asset. Since every transaction on the blockchain is recorded, verifiable, and unfalsifiable, the origin and circulation of a particular asset are public information.

A smart contract is a self-executing contract that has the terms of the agreement between the parties written into its code. When predetermined conditions are met, the contract executes all or parts of the agreement, with the transaction being recorded on the blockchain. Think of them as digital “if-then” statements.

Each of these qualities is valuable in and of itself. Combine them, and you get something quite special.

Imagine being able to pick and choose from other creators' work to come up with you own personal aesthetic, a collage of ideas drawn from across multiple media and genres. What if you could direct a horror film with Wes Anderson's color palette or Wong Kar Wai's slow motion savvy? No fine-tuning needed: you'd simply plug in the right set of parameters and let the associated aesthetic take over.

All the while, every aesthetic layer you'd be using would come with attribution and monetization built-in, sending recognition and revenue upstream, back to their original creators. If a creator wished to keep control over their aesthetic, they could also make it so others would be unable to mimic their style: combining too many of their signature traits could trigger a copyright infringement. In theory, such a world would enable artists to embrace, not fear, the open circulation of their aesthetics.

I'm not saying this is a desirable future, mind you. Artistic movements from the past were possible because artists were free to use a particular set of aesthetic primitives that they felt personally drawn to. There was no entry cost to consider, no gatekeeper to bribe or circumvent in order to begin painting, filming, or playing music in a certain way. A healthy mix of collaboration and competition enabled artists to both build on one another's work and come up with their own takes by accentuating or dropping specific aspects of that style: general adherence to a school still allowed for singularity. In contrast, granular control over a particular aesthetic, especially when enforced at the technical layer through automatic attribution and restrictions, feels like a serious threat to aesthetic innovation at large.

It also raises questions on what an aesthetic even is: that is, how much, or how little, of someone's distinctive style you're allowed to draw from before it can be legitimately considered plagiarism.

Music is a case in point. While a song could technically be decomposed into distinct components such as its tonality, melody, harmony, lyrics, and tempo, no one element is usually enough to signal an intent to copy an existing piece of work. Consider melody: if your music follows the rules of a particular musical scale, which most music does, there are only so many notes you can play with after all, meaning recognizable patterns are bound to reappear in sometimes vastly different tracks, whether intended or not. This makes the issue of "substantial similarity" — whether or not the average listener can tell that one song has been copied from the other — a blurry one.

In a world of instant composability, distinguishing inspiration from infringement, and homage from grift, could be especially tricky, no matter the medium.

A creator's greatest strength is also their greatest weakness: to be recognizable is to be imitable. The very reason why people can compose, paint, or sing "in the manner or [X]" is because we, as consumers or critics, have reached a common understanding of what constitutes an artist's style. These are the creative idiosyncrasies that homage and pastiche live off: both work only to the extent that the source material remains indentifiable.

With software-based experiences, artists now have an opportunity to disseminate their vision while also reaping the cultural and financial benefits that have long escaped them. In this new paradigm, their influence and viability rest as much on their singularity as on their willingness to share it with the world, ready for anyone to use. As it continues to spread, fork, and mutate, an aesthetic will live a thousand lives.

Thanks for reading. If you found this issue valuable, I’d really appreciate it if you could forward it to a friend, or share it with the world.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts! You can find me on Twitter, or just reply to this email.