A Playbook for Playful Publishing, Part II

On Judging Books (and Publishers) by Their Covers

Hi there! I’m Maxime, and you’re reading Recreations, a newsletter about the intersection of media, technology, and culture.

You’re receiving this either because you subscribed or because someone forwarded it to you. If you’re in the latter camp, you can subscribe here or via the button below.

Welcome back to another installment of A Playbook for Playful Publishing.

In Part I: The Promises and Trappings of BookTok last week, I unpacked BookTok’s workings, why the platform might have looked so appealing to publishers when it emerged, and why its ever-growing influence actually threatens the industry’s long-term prospects.

This week in Part II: On Judging Books (and Publishers) by Their Covers, we explore exactly why we care about a book’s cover so much, what messages it sends and to what purpose, and why its pull has never been stronger.

Here’s what’s in store for the coming weeks:

Part III: The Playbook will lay out five strategies that publishers can explore to generate engagement and revenue, and to grow awareness beyond individual IP and toward their own brands. And finally,

Part IV: Monsieur Toussaint Louverture: Publishing as Craft will be a deep dive into Monsieur Toussaint Louverture, a French publisher whose opinionated curation and attention to detail represent the best of what indie publishing can be.

If you haven’t already, make sure to subscribe so you get every installment straight into your inbox.

If BookTok Is a Stage, Books Are The Props

Last week, I described the many ways in which BookTok’s rise has upended book publishing. As I wrote then: “From rights acquisition to promotion to distribution, professionals across the industry have rushed to adapt their practices in order to better cater to the community’s demands. […] Wherever you look, BookTok — what the community wants, and how to deliver it — is now the single biggest motivation behind the industry’s every move.”

Equally significant is the platform’s impact on reading itself. I’m not talking about numbers here — if you’ve read Part I of this series, you already know about those. BookTok has, undeniably, boosted sales and grown the reader base. But it has also transformed reading as a cultural practice, making it more expansive and more performative. Many in the community not only share reviews of the books they’ve read, but actually film themselves reading them. Crying Reading, sometimes performed live, has grown into its own category, with sobbing close-ups raking in millions of views.

If BookTok is a stage, then books are unequivocally the props. In fact, the community appears to value them, as objects, at least as much as the stories they contain. From leather spines to sprayed edges and from book swag reviews to shelf staging tips, the overlap between reading and home decor has grown so strong that creators on the platform are striking paid partnerships with… paint companies. Some have seen this interest as a sign of the community’s blatant shallowness. Last year, GQ wrote that “the TikTok books community is more about a lifestyle aesthetic than actual reading” and denounced “a showy nothingness that only approximates bibliophilia.”

Still, we should be careful not to overgeneralize, especially since this criticism happens to be directed at a largely female, younger base. Gatekeepers have a long history of dismissing any cultural practice that they deem unserious, and therefore, illegitimate. From novel reading to Beetlemania to the “Swifties”, young women’s excitement for culture has always faced ridicule. And with its millions of romance-reading, special edition-loving enthusiasts, BookTok leaves itself wide open to sneer.

But what if, instead, we took the matter seriously? With its “book hauls” and aspirational bookshelves, TikTok’s flavor of reading is proof that culture is embedded in a larger system of consumerism. So what? If we abstain from value judgments on what type of literature people ought to be consuming, or what their bookshelves ought to look like, there is a lot we can learn from the way reading is actually practiced on the platform.

However materialistic — or rather, because it’s so materialistic —, BookTok offers the best vantage to analyze what readers expect from books and the companies behind them.

Unpacking the Book Cover Trifecta

Why is the book cover so important? I think it comes down to three things: legibility, recognizability, and desirability. Each of these components aims to convey information in a different way: legibility at the genre level, recognizability at the publisher level, and desirability at the book level. Let's cover them in turn.

Legibility

Take a quick glance at the stands of any bookshop, or your own bookshelf, and you'll find that publishers seem highly predisposed to imitation. From the headless woman to flat design, from the Blob to the Portal, visual styles and themes regularly pop up, grow, and end up taking over the industry's imagination as well as its design budget. Trends may come and go, they may not all be equally fashionable or last equally long, but take any point in time and it's rare that there isn't at least one of these making the rounds from one book cover to the next.

There's a simple reason for this phenomenon: the quest for legibility. For publishers, tapping into a particular aesthetic is an easy way to signal which genre or tropes their books abide by. A blurry silhouette in blue hues? That's a Nordic noir. Vibrant colors and a Tumblr-esque curvy font? That's a quirky summertime romance. With book covers as with movie posters, visual conventions act as heuristics, encoding consumers' expectations as to the actual content by appealing to prior and collective cultural knowledge. The longer a trend lasts, the more the clichés solidify, the clearer the signal. Some of them have been around for so long that it's almost impossible to point to their beginnings, that one cover from which all the others followed. But consider a shorter time frame, and it becomes clear exactly how much a Twilight or a Fifty Shades of Grey can set a genre’s visual standard for years to come.

There are, of course, decreasing returns to imitation. Just like publishers, frequent readers are very much aware of the book cover meta; after a while, they start to get suspicious of yet another lookalike trying to lure them on looks alone. But however formulaic this may seem, the fact that publishers keep following this tactic proves that there is still upside to doing so.

Recognizability

Where legibility is about adhering to industry-wide codes, recognizability is about asserting a unique visual identity. With the former, the logic is extrinsic, imposed by cultural standards solidified over years and sometimes decades. With the latter, the logic is intrinsic, motivated by your company's own guidelines and business objectives.

A visual identity can include many things, from a cover's layout and materials to a color palette or a proprietary font. Together, these components help readers associate a book with a certain publisher, improving the odds that they will turn to the same name again if they're ever looking for similar reads. This explains why specialized imprints and collections tend to be the most aesthetically opinionated: by standing out visually, they can better convey their editorial singularity and stay top-of-mind in a niche branch of knowledge or literary genre. In France, Editions Divergences, Editions Wildproject, Editions Zones, and my personal favorite Monsieur Toussaint Louverture have been pushing the envelope in this regard.

As with legibility, there are limits to this strategy.

First, recognizability takes time and prolonged exposition before readers are able to pattern-match. For this reason, it needs to be considered and standardized as early as possible. Logistically, there is nothing worse for a publisher than to have to redesign its earlier releases after a brand overhaul. The sooner a visual identity is established in the marketplace and the longer it can compound from one book to the next, the stronger and more valuable it becomes.

Second, a unique identity really only makes sense for books that are similar in one way or another — think fiction vs. non-fiction, novel vs. poetry, or fantasy vs. sci-fi. The conglomerates that dominate the industry with a yearly output in the tens of thousands and all-encompassing catalogs can't afford to operate as only one brand ; in publishing, economic consolidation needs brand fragmentation. Once a certain category grows large enough in a portfolio, a new, distinct imprint should be spun off with its own branding to ensure more granular brand recognizability for readers and brand management for the publisher. Hachette Group, for example, has dozens of divisions and imprints, from Balance ("a practical nonfiction imprint built with the whole person in mind") to Redhook ("commercial fiction with speculative elements"). The more specific the editorial stance, the easier it should be to come up with a unique aesthetic that reflects it.

Desirability

We arrive at the third and last component of the conundrum: desirability. On that note, anyone who's ever bought a book at random knows how much first impressions matter. The first job of a cover is to arrest you, to call to your taste and curiosity enough to make a book desirable before you know anything about it.

It doesn't need to reveal much. As I've mentioned, the industry has grown to embrace increasingly abstract or even obscure motifs, to the point where a book's contents and design might feel almost unrelated. The greater the disconnect between the two, the more blatant the cover's role as a decorative or even seductive device, rather than an informative one.

Not all buyers feel this pull with the same intensity. When asked what might prompt them to buy a book, 72% of French 25-34-year-olds and a whopping 78% of 15-24-year-olds mentioned the importance of a book's cover, compared to just 56% among the general population and 35% of readers 65 and more.

This varying sensitivity can be partly explained by age: arguably, the older you get and the more you've read, the more you understand that what matters is a book's content, not its looks. But there's a generational, technology-induced shift at play, too. The 15-34 year-olds who took part in this survey grew up with something their predecessors didn't have: the internet and, more specifically, social media. For younger generations shaped by digital culture, books have transformed into more than just a literary experience; they are at once aesthetic artifacts and status symbols. The cover is, itself, Content material, waiting to be shared and broadcast.

“Pick two of three”

Genre / legibility, publisher / recognizability, book / desirability: these are the three layers of information that a cover should ideally convey in order to make a book's value proposition clear to potential readers.

Balancing all three isn't easy. Lean too heavily on industry-wide visual codes, and your book will lack individuality — and therefore, desirability. Focus too much on making a particular cover stand out, and readers may fail to recognize the brand behind it.

In practice, different categories of publishers will generally favor one goal over the others based on their unique strengths and constraints. Large publishers, for example, enjoy inherently greater recognizability due to their longevity and the sheer size of their catalogs. Meanwhile, what indie upstarts lack in scale, they often make up for in astuteness. More culturally aware, more digitally savvy, they are better able to tap into short-term graphic trends for legibility. Conversely, they might invest more heavily on developing a unique aesthetic to better stand out in the marketplace. Finally, there are the growing numbers of self-published authors who, because they lack both the ability to design a stand-out cover for their work and the resources to delegate that task, may be forced to turn to freelancers and to default to a genre's visual tropes.

At the end of the day, we as readers unashamedly judge books, and the companies behind them, by their covers. Whichever aspects of the Book Cover Trifecta they choose to prioritize, publishers would be wise to remember that fact.

Why The Book Cover Matters More Than Ever

Putting in the effort has never been so crucial. Several catalysts — part technological, part cultural — have reinforced the cover's importance, making it more central a choice criterion and granting it cultural weight in and of itself. Together, they help explain the materialistic impulses that have grown so prevalent among today’s readers.

Ecommerce

The emergence of ecommerce didn't just change how books were bought; it also changed what they looked like. Online, books were visually and symbolically flattened, their physicality compressed into thumb-sized vignettes and drowned in hyperlinks and metadata (ISBN here! Dimensions there!) that crowded every page.

Competition was also orders of magnitude greater overnight. Jeff Bezos famously picked books as the first best product to sell online because "there are more items in the book category than there are items in any other category, by far." For Amazon, this meant an endless supply of titles to sell; for authors and publishers, more competition than they'd ever encountered in any bookstore. Unless yours was the type of book that people know and search for by name, your work was now crowded out. Available everywhere, yet invisible.

The combination of the two — the flatness of the interface on the one hand, the overcrowding on the other — meant the need to catch buyers' eyes was stronger than ever. As Vulture wrote in 2019: "At a time when half of all book purchases in the U.S. are made on Amazon — and many of those on mobile — the first job of a book cover, after gesturing at the content inside, is to look great in miniature." Publishers upended their design practices to adapt to the new environment; graphic fonts replaced hand lettering, which translated poorly in a digital setting.

By now, most in the industry have learned to play by these rules. But there is always room for improvement — especially among the self-publishing crowd. Years ago, design marketplace 99designs ran A/B tests to see which version of a book’s cover performed best in Facebook ads. It found that the new, redesigned book covers generated on average 51% more clicks than the originals, with improvements in click-through rate ranging from 6% on the low end to 122% on the high end.

Of course, people still buy books offline. But even then, someone's first encounter with a particular book is likely to have been in pixel form, in a staged photo or a fast-paced video review. The cover-as-vignette, then, serves a double purpose. If it's not enough to instantly elicit a purchase, it can still successfully imprint on the consumer's mind until they come across that same book somewhere else. Here's Vulture again:

In a marriage of irony and logic, a book that pops in a filtered miniature Instagram still life can declare its presence just as loudly from across the room, particularly in the boutique environment of the modern independent bookstore. [...] So we find ourselves in the recursive modern world of bookselling, tumbling through an endless loop from the physical to digital and back again.

BookTok epitomizes this recursivity better than any platform before. Focusing on video from day 1 made the platform inherently conducive to formats like product reviews and hauls, which fed into real-world businesses. This, in turn, made retailers inclined to cater to the platform’s audience in ways that they hadn’t for either BookTube or BookStagram. Finally, with content and commerce now fully integrated via TikTok Shop, virtually every review on the app can lead to dozens more copies making it into dozens more hands — with those same hands creating content, ad infinitum.

Shelf Aesthetics

For as long as there have been books, people have had opinions on how to organize them. Today still, team alphabetical and team color continue to go at it, seizing every opportunity to claim the superiority of their preferred method over the other. Do you prioritize aesthetics, or practicality? Do you go by discipline, or free association? We may fill our shelves with books, but we imbue them with meaning.

A few years ago, COVID-19 pushed these concerns to the max. As work communications defaulted to video and everyone suddenly became privy to their colleagues' interiors, many at home felt the need to upgrade their video backgrounds. Offices turned into Zoom rooms. The credibility bookcase became the quarantine's hottest accessory, equally a token of authority and a puzzle for outsiders to decipher.

It wasn't just about how many books you had, either; it also mattered which books you had. Books can signal not just a person's tastes but their beliefs and allegiances, too. In 2020, Robert Caros's 1974, four-pound, 1,246-page biography, The Power Broker became "a must-have, must-be-seen accessory for several reporters." Tellingly, in Washington, requests for shelf staging tend to shift left and right across the political spectrum depending on which party sits in the White House. You're only one book away from a cultural faux-pas.

It may be tempting to dismiss this trend — many in the industry have. Arguably, the more we consider books for their aesthetic or social value, the less we care about their actual contents. But that phenomenon would be neither new nor specific to the written word. As shared by former Spotify chief economist Will Page:

"60-ish % of the vinyl buyers don't own a record player. So that 40%, how many have bothered to open the record? Maybe half. So that takes us to the point where 80% of what's being sold isn't being consumed. Which, by the way, is how the book industry works. The book industry works off a rule of thumb that 80% of books that are sold are not being consumed by the reader. They are gifts, they sit on a glass table [...] There’s a long history of selling content that’s not there for its consumption."

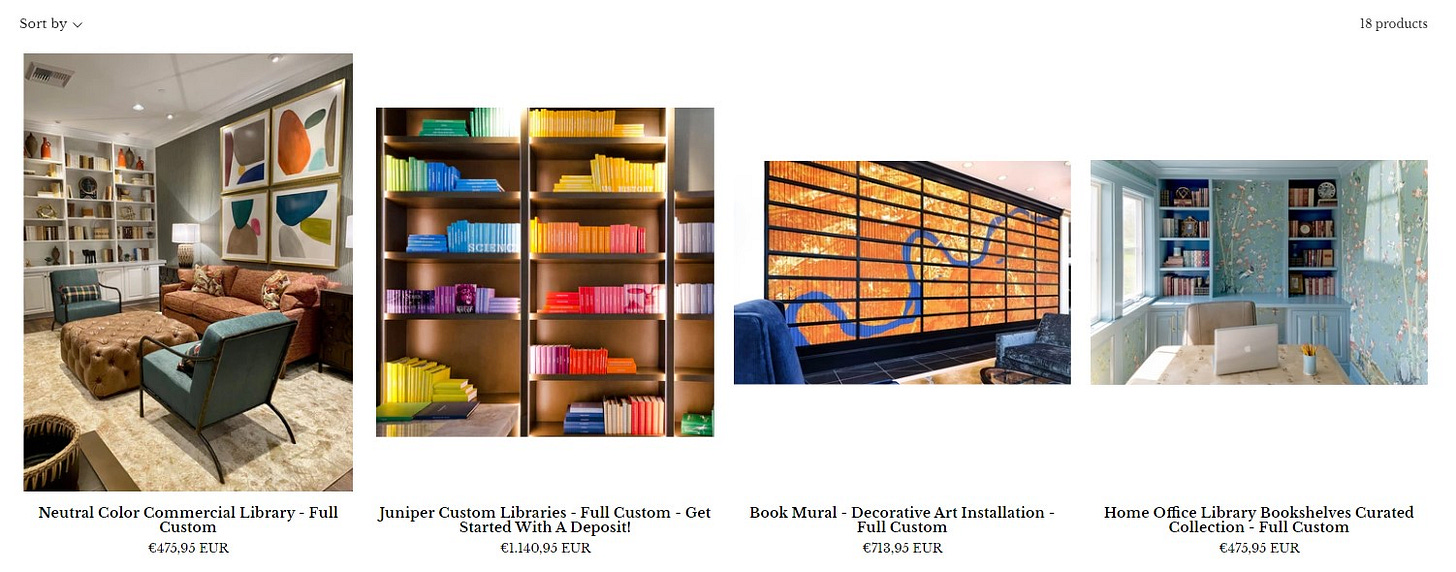

For some, this disconnect has been nothing but a business opportunity. Dozens of companies now provide ”books-by-the-foot" services, which, as their name entails, sell books wholesale to the surprisingly large number of individuals and institutions that want their shelves promptly yet aesthetically filled. Based on a brief or more in-depth analysis — anything from a client's interests to a hotel's guest profile —, books are first picked by color, size, theme, period, or a combination of those, then curated and shipped as sets, ready to be displayed. In some cases, installation and regular replacements, or "updates," are also possible.

Leading the way is Juniper Books, which provides ready-made libraries and designs and prints bookshelf-enhancing editions of popular books and series, with best-sellers including Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, and The Wheel of Time. A "Jackets Only" category also allows collectors to retrofit their hardcover books at a lower cost so they offer a more consistent sight. Thatcher Wine, the company's founder and CEO, boasted how "someone can have the complete works of Jane Austen, but in a certain Pantone chip color that matches the rest of the room or with a custom image."

Though it's hard to say how big the market is, shelf staging is real and only growing. BookTok is certainly contributing — for some reason, the Venn diagram between romance readers and shelf stagers is almost a perfect circle. More generally, though, the books-as-decor trend feels like the logical outcome of centuries of bibliophilia, an unapologetically consumeristic celebration of erudition, or the semblance of it.

The Longing for Analog

Taking a step back, our current obsession with books as objects can be weaved into a larger story: the longing for analog.

Interest in crafts — whether that's practicing them or supporting those that do — has been growing in the West. 2023 marked the 18th consecutive year of growth for vinyl in the U.S. Wired headphones are in again, as are dumb phones. It feels like the more digital stuff we surround ourselves with, the more screens we are forced to use to complete even the most mundane tasks, the more we crave for tangible objects and activities to counterbalance that trend. Discussing the so-called vinyl revival last year, The Observer tellingly called LPs "the antidote to a frenetic digital world" and praised "the heft of things we can hold in our hands."

That craving very much applies to books, too. In the same way that manipulating vinyls in an mp3 world can feel like a ritual of sorts, the sheer materiality of paper books offers a respite from our all-digital day-to-day. The appeal is especially strong on younger readers, with social media fueling the romanticization (or fetishization) of reading and everything that comes with it. (As I wrote last week, this is a striking irony in the fact that we use screens to revel in physical items, and social media to lament the loss of third places. Such is the state of things!)

Memetic nostalgia aside, digital fatigue is real. Due to top-down technology adoption in education and the workplace, textbooks are increasingly being accessed in digital form. According to the World International Property Organization, in 2022, digital and audio accounted for 47.5% of publisher output in the trade and educational sectors in Norway, and over 72% in Brazil. With digital so inescapable, simply collecting physical books on your own time and for your own pleasure is starting to feel not just like an indulgence but like an act of cultural resistance.

Taking a Cue

On the surface, BookTok’s emphasis on books as aesthetic objects, rather than just literary experiences, may seem like a troubling development, a sign that readers are more interested in appearances than substance. But to dismiss it as mere consumerism would be to miss the deeper currents at play.

Whereas the book cover was always used unidirectionnally by publishers to serve their goals, it has taken on new significance as a way for readers to express their identity and find community. With their tactile allure and visual presence, books are tangible things that people can revel in, engage with, and bond over — whether they read them or not. In an increasingly digital world, their pull has never been stronger.

For publishers, this is a valuable lesson that cultural shifts bring tangible business opportunities. Today, readers are seeking out analog experiences that engage their senses and deepen their bond with the texts they love. The book, as an object, is only one of many possible touchpoints. Whatever it takes, publishers should see themselves as in the business of bringing stories to life.

That’s it for Part II! In Part III next week, I’ll lay out five strategies that publishers can explore to generate not just engagement but revenue, and to grow awareness beyond individual IP and toward their own brands.

Thank you for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this essay, please consider giving it a like and take a minute to share it with others. It really helps.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts! You can find me on X, or just reply to this email.

Thanks to Jimmy for reviewing a draft of this piece.

Thanks for the post! Great as usual!

I find it super interesting to read about BookTok (which I discovered through you; I had no idea it existed) and now about book covers, as these are two aspects that don’t exist in what makes me happy while reading.

I transitioned to full Kindle about 7-8 years ago, and since then, I have to admit that I don’t miss the physical experience of reading a book. In fact, I think a Kindle provides a superior reading experience—it's more convenient, easier to transport, allows me to switch between books, take notes, and read in the dark, etc. The cover aspect is completely absent from my decision-making criteria (on Kindle, I don’t even know what the cover looks like).

The only exception for me is cartography books, which I love, and I have a couple of them at home.

I might be wrong, but from what I read through your article (like people recording themselves crying while reading books) it seems that there's a lot of "signaling" there and people do it more to attract views than for the joy of reading. But I might too old to understand this way of consuming books.