Fever: Fun Factory

Building the operating system of live entertainment

Hi there! I’m Maxime, and you’re reading Recreations, a newsletter about the intersection of media, technology, and culture.

You’re receiving this either because you subscribed or because someone forwarded it to you. If you’re in the latter camp, you can subscribe here or via the button below.

Fever’s Rise

On a beautiful evening in Madrid, hundreds of faux candles flicker to life inside a centuries-old concert hall. A string quartet begins to play Coldplay’s Yellow. The crowd — young, connected, affluent — leans in. In that moment, the experience feels unique; it isn’t. That same week, thousands more will enjoy the same performance in a church or a museum, somewhere in New York, Paris, Sao Paulo — or any one of the 150 cities where Candlelight now operates. The same format, the same aesthetic, the same programming, the same quiet magic. What began as a one-off experiment is now a global franchise.

This is Fever’s genius.

Fever was founded in 2010 by Josep “Pep” Gómez, an 18-year-old from Castellón, Spain who launched the company from the dining room of his shared San Francisco apartment. His idea was simple but early: a mobile-first ticketing app at a time when events still lived on desktop. To set it further apart, Gómez added a social layer that turned users’ ticket purchases and attendance announcements into recommendations for others. It was a clever hack, but not yet a revolution.

The real breakthrough came with Fever Originals, a roster of immersive experiences available exclusively through the Fever marketplace. Designed and named after Netflix’s own original content initiative, the label was originally meant only to entice users into adopting the app. What began as a handful of eccentric pop-ups — a “Mad Hatter’s (Gin &) Tea Party” here, a TOTAL RECALL-themed immersive cinema there — has evolved into a disciplined and global catalogue of Insta-friendly experiences spanning intimate music shows, multisensory escape games, immersive exhibitions, dining experiences, and large-scale festivals. Today, Fever Originals is the company’s most defining product and primary growth driver.

Gómez is long gone, but Fever is still run by the same team he hired in 2015 — Ignacio Bachiller, Francisco Hein, and Alexandre Perez. (Interestingly, Gomez’s LinkedIn insists that he was the company’s sole founder, whereas the trio is listed as co-founders both in Fever’s marketing and in the media.) Building off its ticketing core, the company has gone on to cover the entire event lifecycle — from production to discovery and promotion (Secret Media Network), to on-site access & inventory management (Fever Cashless), to live operations and analytics. The result is an end-to-end, data-driven operating system for live entertainment: a platform that doesn’t just sell tickets but helps organizers predict, design, optimize, and scale what audiences want to buy.

And momentum is building. On June 4th, Fever announced it had raised over $100 million in a Series E round led by L Catterton and Point72 Private Investments, bringing total funding to $527 million. The round followed what Fever called a “remarkable” 2024, marked by 20x revenue growth from pre-pandemic levels and full-year profitability. The announcement emphasized that the new capital “[would] fuel Fever’s continued growth in music and sports, two verticals where the company has gained significant traction over the past year.” A day later, Fever revealed the acquisition of DICE — a music- and nightlife-focused ticketing platform — to build what it called “a live entertainment tech powerhouse.”

With these moves, Fever is entering a new phase — one that makes it impossible to dismiss as just another event platform. This makes now the perfect moment to unpack its playbook. Where traditional players like Live Nation are doubling down on blockbuster, hit-or-miss entertainment, Fever is A/B testing its way to success and building franchises from scratch to maximize upside.

This is a look inside the company’s strategy and singular vision for the future of live entertainment. Here’s what’s in store:

A Primer on Fever

Fever’s Formula

Strategic Arenas: Sports and Music

What’s Next: Opportunities and Risks

Parting Thoughts

A Primer on Fever

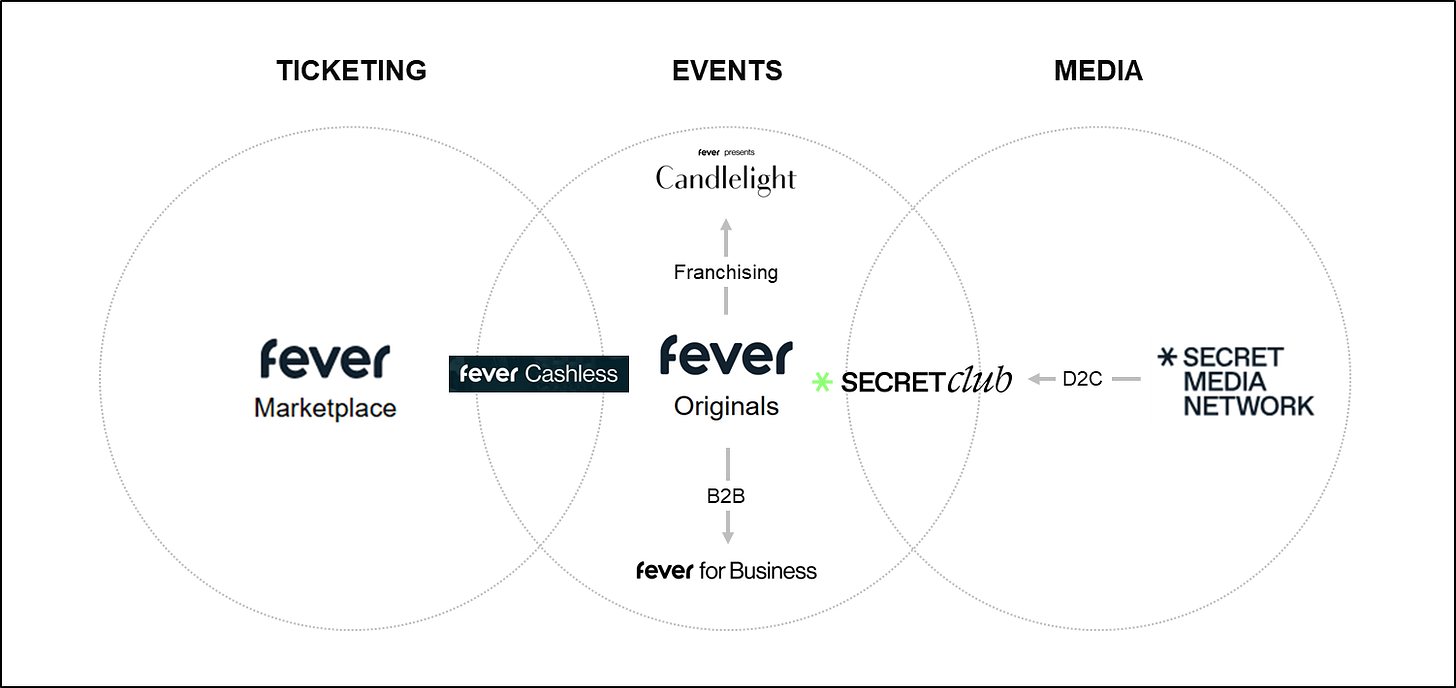

From its humble beginnings as a ticketing app, Fever’s business has vastly expanded over the years. Today, its activities consist of three segments.

Online marketplace & event solutions

Fever operates a global event discovery and ticketing platform that lets users browse and book a wide range of local cultural experiences across sports, music, food, wellness, and immersive entertainment. The company is the exclusive ticketing provider to prominent sports organizations (e.g., FC Barcelona, Real Madrid), event organizers and promoters (e.g., Primavera Sound, Cercle, and Pitchfork Music Festival), and venues (e.g., Clapham Grand and Brooklyn Storehouse).

In June 2025, Fever acquired DICE, an independent music ticketing platform, to bolster its scale and capabilities in music specifically. Since its inception in 2014, DICE has positioned itself as a user-friendly service focused on price transparency, and personalized recommendations. The app notably includes a Wait List feature that lets fans buy tickets returned by other fans, bypassing resellers and allowing artists and promoters to assess demand for additional events.

In addition to its online marketplace, Fever also offers organizers and operators a wide range of on-location services under the Fever Cashless brand. Spanning the entire event lifecycle, these solutions include mobile access control, capacity control, cashless payments, inventory and staff management, self-service kiosks, and more. Clients on this side of the business include MotoGP, Bigsound Festival, and X Games California.

Events production and operations

Fever is directly involved in the production and operations of experiences, with a focus on immersive entertainment. It does so in two ways. Historically, the company has worked with IP owners to co-produce live entertainment formats, including Stranger Things: The Experience with Netflix, Harry Potter: A Forbidden Forest Experience with Warner Bros., JURASSIC WORLD: THE EXHIBITION with Universal Pictures, and, most recently, Dexter: The Experience with Paramount+.

In addition, Fever has also been developing its own range of original experiences, Fever Originals. Despite what the name might imply, not all Fever Originals are owned by Fever alone — many of them are, in fact, co-productions. Today, the category spans a wide spectrum of entertainment experiences, with a focus on multi-sensory and often technology-enabled concepts. This includes Candlelight Concerts, a series of intimistic, (battery-powered) “candle”-lit acoustic concerts; Neon Brush, “a retro-futuristic pop-up painting workshop”; The Jury Experience, an interactive theater experience; and many more.

Despite their thematic variety, all these formats share Fever’s hallmarks. First, they are deliberately social-first. From Neon Brush’s glow-in-the-dark canvases to Bubble Planet’s Insta-friendly backdrops, every detail is engineered for shareability and user-generated content, the lifeblood of modern cultural marketing. Fever doesn’t just rely on this organically: it systematically builds influencer programs into each experience, ensuring built-in distribution among digital-native audiences.

Second, these events are scalable by nature: by focusing on simple, high-appeal concepts, it creates experiences that can seed locally and then blossom into full-fledged franchises globally. Prison Island, for instance, now operates in over a dozen European cities, while Bubble Planet has already landed in 13 cities across Europe, the US, and APAC — with more in the pipeline. Combined with first-party data harvested from its marketplace, this modular approach allows Fever to identify high-potential markets and rapidly replicate its hits with precision.

These two guiding principles laid the foundations for Fever for Business, a dedicated corporate division that serves enterprise clients with custom-built private events and tailored experiential perks. This initiative transformed Fever from a pure ticketing and entertainment brand into a B2B partner capable of orchestrating turnkey branded gatherings and activations.

Secret Media Network

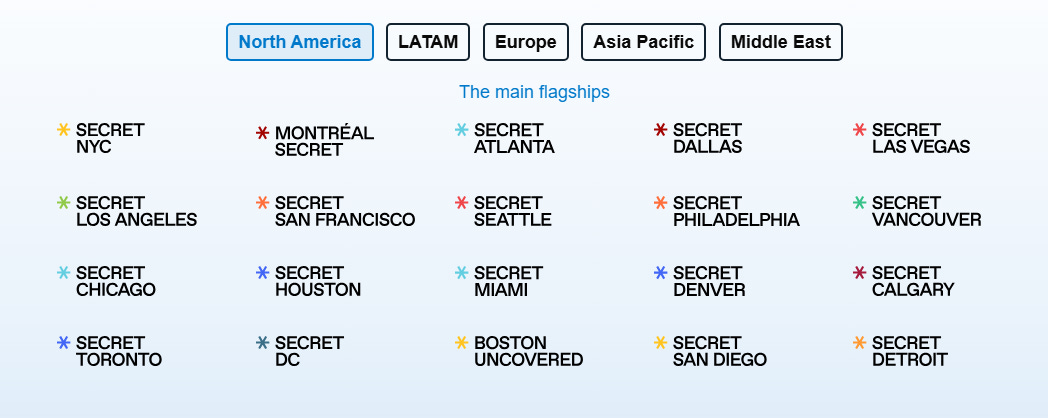

Secret Media Network is Fever’s sprawling ecosystem of over 200 hyper-local digital channels collectively attracting 300M+ monthly interactions.

These channels serve a dual purpose. On the one hand, they generate revenue through a mix of branded content, giveaways, and email campaigns for third-party clients. On the other hand, they act as a powerful in-house marketing engine to drive discovery and ticket sales — particularly for Fever Originals, where the company captures margin not just as the ticketing provider but also as the event operator.

As of recently, Secret Media Network also launched Secret Club, a subscription-based community that gives consumers access to exclusive content, discounts, and perks in their city of choice — only New York and London for now.

Fever’s Formula

Each of these segments could make for an interesting company in its own right, but the real magic is in how they interlock. From its inception, Fever has been building towards a cohesive ecosystem in which data and value are continuously flowing from one business line to the next to uncover new growth opportunities. Audience insights gathered in one corner of the business feed product innovation in another. Mastery over distribution reinforces operational profitability. Brand partnerships make room for proprietary ventures. It’s worth diving deeper into each initiative’s contribution to the whole.

Fever’s “marketing fee”: A value-add take on ticketing

Ticketing, in its basic form, is a low-margin business. On its own, a ticket is essentially just a permission slip, a standardized product with little room for price differentiation from one platform to the next. Try to charge even a few percentage points more, and consumers will defect to another platform, unless the event is locked in by exclusivity. Regulators are paying close attention too. In the US, the FTC recently cracked down on bait-and-switch tactics and hidden fees, forcing companies to disclose the total cost upfront. In such an environment, competing on the ticket alone is a dead end. The real battle lies in the surrounding services: discovery, user experience, data, and everything that can turn a simple transaction into a broader relationship.

Fever opted to turn these constraints into a business opportunity early on. Instead of a traditional, single-digit booking fee, it charges a “marketing fee” “based upon [its] ability to drive additional ticket sales and attendance to [an] event or experience.” Information is scarce and the exact amount is unclear, but in 2018, the company estimated this commission to be “around 3-5 times” that of a “ticketing fee.”

I reached out to Fever to confirm that the model was still current. Here’s what Santiago Soler, the company’s VP Global Communications, Public and Institutional Relations, had to say:

Our philosophy has not changed: organizers pay a commission that reflects the services Fever provides — from marketing and distribution to customer support and technology. The specific structure can vary depending on the type of partnership, the needs of each event, and the preferences of each organiser.

Compared to a normal ticketing fee, this model unlocks several advantages. Chief among them is, of course, the take rate: by serving organizers across more of their needs, Fever can capture a much larger share of value. Just as important, it shifts the narrative. Instead of just “ticketing,” organizers are paying for incremental demand and operational support — services that are both more strategic and harder to commoditize. This framing not only justifies the premium but also deepens the partnership, making Fever less of a vendor and more of a growth engine for its clients. This ensures greater alignment, tying Fever’s upside to its partners’ success.

Still, the model works only if Fever can credibly prove its impact. Unlike a ticketing fee, which is justified simply by processing a transaction, a marketing fee demands evidence: where did the buyer come from, which campaign or channel nudged them to convert, and how much of that revenue can be traced back to Fever’s efforts? Attribution is notoriously difficult in live entertainment, where the customer journey is rarely linear. Someone may hear about an experience through a TikTok clip, see a reminder on Instagram days later, and finally buy after a friend shares a link in the group chat. Untangling this web of influence requires a sophisticated system to track, measure, and attribute sales with precision.

Fever has made these capabilities central to its pitch. Today, it combines user-level tracking — via UTM parameters, pixels, and affiliate links — with higher-level techniques like marketing mix modeling (MMM), which uses aggregated data and regression analysis to assess the impact of both online and offline channels. Because the media rails are Fever-owned, the company can trace the path from a Secret Media post or paid unit to an organizer’s checkout with unusual clarity. In that regard, recent job postings point to a sophisticated internal stack, with real-time data collection from platforms like Meta, Google, and Tiktok; AI-driven pipelines for creative and budget optimization; and the use of causal inference to “determine the true impact of specific marketing interventions.” The result is a system designed not just to monitor performance, but to continuously improve it on behalf of its partners.

In this configuration, filling seats becomes an optimization game — a calculated and ever-evolving equation balancing customer acquisition cost against expected profit per attendee. The better Fever gets at targeting, tracking, and tweaking each lever, the more confidently it can justify its premium and the more value it can capture.

Fever Originals: An all-weather, high-margin roster of experiential concepts

Fever Originals weren’t always what they are today. While one article from 2014 suggested Fever would leverage exclusive events to entice users into using its app, it wasn’t clear then that those exclusives would also be original creations. Fever Originals as an entity was officially mentioned only years later, with early experiments spanning artisanal pop-ups — a “Mad Hatter’s G&T Party” in a derelict double-decker bus in Brooklyn — and hybrid formats — Total Challenge, a TOTAL RECALL-themed immersive cinema experience.

Much has changed since then. Today, the label covers everything from intimate music shows to multisensory escape games, to immersive exhibitions, dining experiences, and large-scale festivals. Some of these concepts are still barely emerging; others have already scaled and can be found across the globe. More than Fever’s flagship, Originals are now also its main economic engine.

What exactly makes something a Fever Original, however, remains hard to pin down. The company’s FAQ describes them as in-house creations, but executives are clear that partnerships are the norm.

Fever Originals [...] is in the business of producing experiences. The strategy is to partner with best-in-class content creators, and to empower them, helping them throughout the production process with data from the decision on the concept until the very end of the journey.

In practice, Fever appears to be highly opportunistic: it may originate a format (Candlelight), co-develop one alongside a creative studio (Astra Lumina with Moment Factory), or take an existing show and put it on a global tour (Titanic: The Exhibition with Musealia). Making a project happen will sometimes require some financial engineering: in some cases, even city governments now sign on as co-producers to secure a local run of a particular attraction.

The throughline is less about ownership than about control. Originals allow Fever to step out of the role of vendor or middleman and occupy the center of the value chain — shaping the product, steering its economics, and, crucially, owning the relationship with audiences. They are Fever’s bet on building a repeatable and highly profitable cultural machine.

Data discipline

The Fever Originals name didn’t come from a vacuum. From the start, the team was “inspired by Netflix’s use of extensive data collection and analysis to make informed decisions about content creation and strategy”, and intent on taking the same approach to live entertainment. Said Global VP of Original Experiences Isabel Solano:

When Netflix started, one of the ingredients that they found would maximize the probability of success when shaping content was the background narrator voice where one of the characters is telling firsthand how they feel, what’s happening, what’s next, et cetera. [...] We wanted to be able to do the same; to identify those ingredients that maximize the probability of success when we’re shaping experiences so that we combine that information coming from the data with creativity to give the result the best chance of success. [...] You need to know whether you should invest $200,000 on a carpet, say, or if there is a better element of the experience that you should invest the money in that will give you a better return on investment.

Data informs every stage of the process, starting with ideation. As TechCrunch once put it, “[Fever is] using anonymised behavioral data-mining to algorithmically predict untapped demand for events that don’t yet exist — and then serving them up as an own brand event.” The “Mad Hatter’s G&T Party” in New York, for instance, was deemed “‘a clear winner’ during [Fever’s] analysis, when it tried out alternative theme options (such as Aladdin and the Lion King), as well as alternative city locations (in other parts of New York), and venues (rooftop, double-decker bus, indoors).” If an experience proves successful, the same kind of analysis can then be used to help determine the optimal route and duration of a tour.

On that note, Fever makes good use of one particular tool: waitlists. On its marketplace, each instance of a particular concept receives its own unique webpage. In some cases, consumers can’t yet buy tickets but are given the option to join a waitlist to “get exclusive access to pre-sale tickets before they are released to the public.” This enables Fever to assess demand locally and make sure an experience settles only where it has the best chances of success. When the time comes, it can use the contact info it collected to retarget those who previously showed interest, lowering customer acquisition costs and decreasing time-to-profitability at the city level.

Engineered scalability

While Fever follows demand closely, its productions also need to satisfy its own business goals. Each and every one of the company’s concepts is designed from the get-go to scale quickly and globally.

No experience exemplifies this fact better than Candlelight. Since its 2019 debut in Madrid, the concept has grown into a blockbuster business that’s now active in over 150 cities and 2,000 venues worldwide. As I wrote in my previous piece, this rollout was made possible by a number of factors:

Broad, evolving repertoire: Originally conceived as a purely classical series (Vivaldi, Mozart, Chopin), Candlelight has since expanded into tributes to pop legends (Queen, ABBA, Coldplay, Ed Sheeran), genre-focused nights (R&B, K-pop, film scores), and seasonal specials (Christmas, Halloween, Valentine’s). Local variations — like a Charles Aznavour homage in France — exist, but the overall editorial stance remains safely culture-agnostic.

Instrumental focus: Performances are instrumental-only, enabling seamless localization without linguistic barriers.

Short, repeatable format: A one-hour runtime lowers audience commitment while enabling two shows per night, maximizing venue yield.

Asset-light model: Candlelight avoids the costs of owning venues or employing permanent performers. Instead, it partners with local musicians and rents existing spaces, reaching scale with minimal overhead.

Operational streamlining: Fever actively recruits new venues and artists through inbound forms on its official site, allowing it to rapidly prioritize high-potential cities and reduce market entry friction.

Integrated promotional machine: As with other Originals, Candlelight rides Fever’s full-stack marketing infrastructure — from affiliate and influencer programs to its Secret Media Network, which subtly plugs shows via seemingly neutral listicles and branded highlights.

Admittedly, not all Fever Originals are music-related, the way Candlelight is. Still, whether that’s duration or operational streamlining, many of the above drivers can be observed across the entire portfolio — proof that the playbook is well established by now.

Importantly, these traits aren’t just design principles for Fever’s own roster; they also serve as a checklist for identifying the third-party experiences most worth courting and bringing onto the Fever marketplace. While some operators may be content pursuing only local success, the most ambitious teams now take a global approach from day 1. To achieve their goals, companies like SENSAS and Paradox Museum standardize set design and deployment, structure clear franchising programs, and share best practices across locations. This emphasis on operational efficiency constitutes the best possible proxy as to a partner’s prospects, and how much business Fever might be able to generate off it.

Asset-light deployment

Among the many factors driving scalability, Fever’s asset-light model deserves emphasis. It stands in stark contrast to Live Nation’s strategy of owning and controlling a significant share of the live music infrastructure. As of December 2024, Live Nation fully owned 32 venues. In Q1 2025, the company announced plans to open “at least 20 large venues (stadiums, arenas, amphitheaters, and large theaters) globally through 2026.” In June, it committed $1 billion to 18 new and renovated venues across the U.S. over an 18-month period.

Ownership benefits Live Nation in several ways. It allows the company to capture a greater share of each fan’s “total concert spend,” especially through ancillary revenue streams — which, at its U.S. amphitheater shows in 2024, averaged more than $44 per head. It also gives Live Nation freedom to act on opportunities at its own pace. At Estadio GNP, for example, per-fan ancillary spend rose more than 30% following refurbishment, proof of the upside that comes with direct control over an asset’s condition and monetization potential.

Fever, by contrast, thrives on flexibility. Concepts like Candlelight or We Call It rely on a global patchwork of small and medium-sized partner venues that are rented rather than owned. Meanwhile, larger ventures, including music festivals or hybrid formats like DroneArt Show, remain too infrequent to justify tying up capital in land or buildings. For these, Fever is better served working opportunistically with cities and venue owners and trading long-term control for agility. This minimizes capital intensity, reduces fixed risk, and makes it possible to scale quickly into new markets.

The trade-offs are real, however. For starters, renting means ceding a portion of the value chain in the form of ancillary revenue — though the focus on short formats would arguably leave little dwell time and few opportunities to consume anyway. Fever also faces recurring exposure to landlord negotiations, local regulation, and availability constraints. Tellingly, a job posting for a Regional Real Estate Expansion Manager position emphasized the need to operate “within demanding time frames.” Securing suitable venues for high-demand events can become a bottleneck, especially when formats rely on distinctive aesthetics or large capacities. For projects with proven staying power, Fever may well seek long-term leases or multi-year agreements with host cities — if it hasn’t already.

Brand extension

If scalability maximizes reach, brand extension maximizes depth. Once an Original has proven it can travel, Fever works to stretch its commercial surface area. Once again, Candlelight serves as the prototype. Originally a stripped-down recital format, it has since evolved into a flexible stage for third parties, from Warner Bros.’ centennial and Netflix’s Bridgerton tie-ins to bespoke artist showcases. Each partnership layers new meaning onto the brand, ensuring its appeal outlives any single repertoire.

The same logic underpins Fever’s move into B2B. With Fever for Business in 2024, then the dedicated Candlelight for Business in 2025, the company began repackaging its hits as corporate, fully-customizable solutions. Candlelight’s modularity makes it especially attractive here, enabling it to be turned into a client dinner, a team-building perk, or a branded activation without losing its core identity.

In both consumer and corporate channels, the strategy is clear: extend the lifespan of winning formats by reframing them as platforms. This extracts more value per format — increasing the ROI of creativity — and reinforces the Originals brands as a system of reusable, adaptable experiential IP rather than one-off shows.

Endless ideation

As the Originals portfolio grows bigger, coming up with new formats gets more difficult. To make sure it never runs out of concepts, Fever has largely systematized the ideation process. Today, a new experience will usually come from any one of the following tactics:

Derivation: Once a concept has proven itself, Fever will often just… create more of it. For example, We call it Jazz, itself part of the We call it franchise, now includes a “Tribute to Soul” variant. This improves repeatability, extending both a concept’s cultural lifespan and its commercial runway.

Mix-and-match: Fever will sometimes mix and match two distinct concepts to come up with a new, third one. DroneArt Show, a “unique fusion of drones and live classical music,” is essentially a drone-enhanced Candlelight.

Commonality: Despite very different concepts, multiple experiences often share the same trait. For example, We call it Ballet, Glow Circus, or The Colorbeat Drums all draw much of their appeal from their LED-enhanced costumes and set designs. This likely enables Fever to pool equipment, resources, and possibly even talent across multiple cultural offerings, thus dramatically streamlining operations. For example, all three experiences (and several others) are currently live from the same venue in Paris.

Imitation: Inspiration can come from observing culture at large — or just competitors. The First Round, “an exclusive social dining experience”, draws from the exact same promise as a company like Timeleft.

Replication: If a concept proves commercially successful but its first run comes to an end, Fever will gladly support new iterations, often with new partners. Since Titanic: The Exhibition (with Musealia), Fever has been involved with The Legend of the Titanic (by Madrid Artes Digitales and FKP Scorpio Entertainment), Titanic: An Immersive Voyage (a coproduction with Exhibition Hub), a second Titanic: The Exhibition (this time alongside Imagine Exhibitions), and even its own Original, Titanic: A Voyage Through Time — which is also made available to operators on a licensing basis.

Together, these various methods ensure that Fever can continue to grow its catalog while also doubling down on its successes. At any given time, the company is sure to have a steady flow of formats that can be tested, scaled, and monetized with minimal downtime.

Strategic resilience

Last but not least, Originals insulate Fever from most of the volatility of the wider live entertainment industry. Live Nation’s own risk disclosures admit how dependent it is on a handful of artists willing and able to fill stadiums. Per its annual report:

Since we rely on unrelated parties to create and perform at live music events, any unwillingness to tour or lack of availability of popular artists could limit our ability to generate revenue. [...] In particular, there are a limited number of artists that can headline a major North American or global tour or who can sell out larger venues, including many of our amphitheaters. If those artists do not choose to tour, or if we are unable to secure the rights to their future tours, then our concerts business would be adversely affected.

By contrast, the concept-centric Candlelight or We Call It build loyalty around the experience rather than the headliner. This gives Fever a hedge against the vagaries of touring schedules and the superstar economy. The stronger the concept’s own brand equity, the less reliant the company is on any one performer or intellectual property, and the more bargaining power it retains in negotiations with partners, sponsors, and rightsholders.

Of course, Fever is not quite self-sufficient. By leaning harder into big-ticket partnerships in music and sports, the company arguably re-exposes itself to the very dependencies it has so far managed to escape. Even within immersive entertainment, a few key partners still account for disproportionate ticketing volume, meaning Fever must devote white-glove resources to them. Nonetheless, Originals give Fever optionality — the ability to keep experimenting and monetizing even when external supply wobbles.

Secret Media Network: Multi-channel demand generation

Secret Media Network is Fever’s universal demand engine for its own formats and for third-party organizers on the marketplace.

Today, the company creates content in more than 20 languages across more than 200 city-specific channels spanning dedicated websites and social accounts on all the major platforms. Together, these channels bring the network’s reach to 31M+ monthly page views and 100M+ videos watched per week.

Naturally, these numbers are unevenly distributed, with major cultural hubs like New York, Paris, and London getting the bulk of the engagement. However, Fever is careful not to overlook any of its markets, and creates channels even for seemingly secondary cities. Whether it operates original experiences of its own locally is irrelevant; as a ticketing provider, it benefits from serving local businesses and institutions nonetheless. The content of each city-specific guide is made available in multiple languages — Bordeaux has two, whereas Paris and New York have seven — to make sure it’s able to tap not just local but time-sensitive, international demand as well.

As mentioned, the network’s model is twofold. On the one hand, it works with third parties big and small that are interested in tapping its audience to generate local awareness in their products and services. To that end, these companies can pick and choose from a wide range of options including branded posts, email campaigns, and more. On the other hand, Secret Media Network’s various touch points are used to direct traffic to Fever’s event marketplace. Crucially, Fever’s editorial control allows it to subtly (and, sometimes, not so subtly) prioritize its own experiences in supposedly neutral city guides.

This tactic is all the more impactful that few consumers even realize that media and marketplace share the same parent company. Pick any one of Fever’s concepts and you’ll find the city-specific instance of the network featured as one its “Media partners” — global franchises like Candlelight Concerts and We Call It, which operate across dozens of territories, list the more generic Secret Media Network. But nowhere is it mentioned that Secret Media Network itself is run by Fever. That information is displayed only on Fever’s and Secret Media Network’s corporate-facing websites, far from (most) consumers’ eyes, helping preserve the air of objectivity that’s key to Fever’s covert cultural curation.

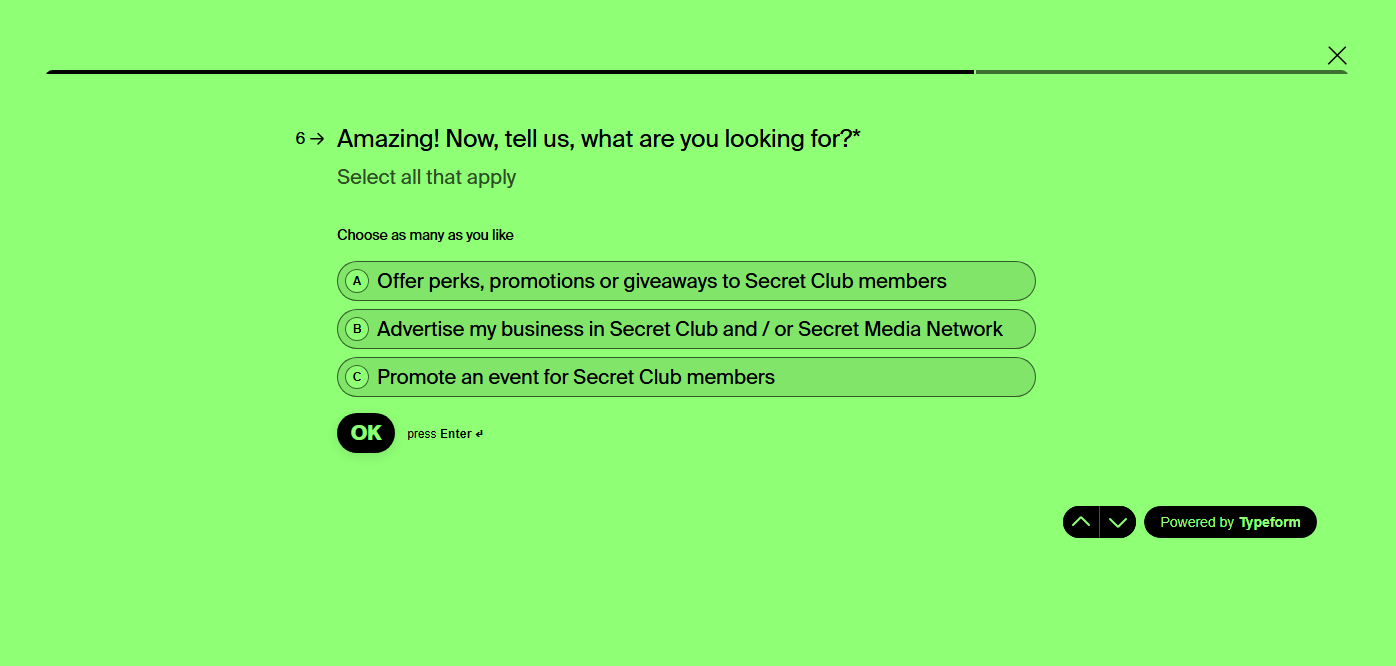

The recently launched Secret Club complements Secret Media Network perfectly. Beside the subscription revenue — the community is currently priced at a reasonable $3.99 a month, or £3.99 in London —, it offers yet another touchpoint for brands and businesses to tap into Fever’s audience. In line with Fever’s habit of streamlining every aspect of business development, an open form on Secret Club’s website already lets prospective partners reach out to propose their preferred form of collaboration.

Like the rest of Social Media Network, Secret Club will drive traffic back to Fever’s marketplace, where the company can take its fee and further refine its understanding of consumers’ tastes and purchasing behaviors. Importantly, Fever benefits on both the demand and the supply sides of the equation. The more perks and discounts it offers, the more attractive the Club becomes, thus driving subscription revenue; in turn, the more consumers there are in the Club, the more attractive it becomes for brands as a marketing channel, driving advertising revenue. In the process, Fever gets to be the interface and kingmaker through which consumers engage with everything their city has to offer in terms of culture and entertainment.

Fever Cashless: From operational excellence to insights generation

Planning and running events is a logistically challenging endeavor, with vendors to source and orchestrate, staff to recruit and train, software to pick and often debug, and countless unforeseen emergencies to resolve. The bigger the venue and the more numerous the crowd, the higher the stakes and the more potential failure points organizers need to consider. This makes operational support all but necessary for most.

Fever has turned these pain points into a business opportunity with Fever Cashless, its proprietary suite of cashless payment and access control solutions for the entertainment industry. Covering the entire event lifecycle, Fever Cashless lets event organizers and venues “reduce queues, reduce staff, enhance security, manage prices and stock in real time, track staff performance, and understand user habits.”

The go-to-market is straightforward. By starting as the ticketing provider, Fever already sees which events are growing fast and which organizers may be hitting operational limits. It can then upsell Cashless services into the same accounts, turning ticketing into a wedge for deeper integration. As of August 2025, Fever claims to have served 8M+ guests and processed $250M in transactions across 1,000+ events.

This isn’t a white-space idea. Live Nation has run Nexus, its own partner network, for over a decade, connecting clients with vetted third-party solutions for everything from entry systems to analytics and loyalty. The initiative has proven successful: 90% of Live Nation’s clients have an integration with one or more of its partners. But Nexus is essentially a directory, whereas Fever offers an integrated, unified stack under its own brand. In practice, it means that ticketing, access, concessions, and vendor management all flow through a single system rather than a patchwork of providers. This makes the product easier for partners to implement, and for Fever to sell.

Operational benefits are clear: frictionless events drive revenue. Festivals that go cashless see faster queues, more transactions, and higher spend per head. One operator found cashless systems boosted the number of transactions by 20% and spend per transaction by 24%, overall amounting to a 16% boost in revenue per head. It’s no surprise that many of Fever’s own Originals now run “cashless only,” both to maximize margin and to showcase the technology to prospective partners.

Yet the deeper advantage lies in the data exhaust. Organizers typically have little insight into how individual participants spend their time and money once they’ve passed the gates. Meanwhile, their sponsors often rely on clumsy surveys or social mentions to prove engagement. With RFID wristbands and digital wallets, Fever can map a participant’s journey across time and space — what they buy, where they linger, which activations they interact with. Every additional touchpoint enriches organizers’ understanding of their guests, enabling them to fine-tune pricing and programming and strengthening sponsorship packages.

For Fever, those insights have even broader value. Embedded into dozens — and soon hundreds — of events big and small, Fever Cashless paints a comprehensive picture of the industry’s inner workings. Which concessions perform best? How much staff is needed? What can be optimized or, better, fully automated? These learnings can then be passed down to future Cashless clients on an advisory basis or implemented across Fever’s own portfolio. In anonymized form, they could also form the basis for future content marketing, much like Live Nation’s regular industry reports.

Fever learns just as much about event-goers as it does about events. On that note, its view of consumer behavior isn’t just individual but indeed nominative. By encouraging guests to credit their wristbands ahead of time, it’s able to connect their on-location behavior to their prior purchases, potentially even their online interests if they happen to have connected their socials. This enables it to form a detailed profile for every participant, including everything from their dwell time to their spending habits. In turn, these insights can be used to prioritize the highest-value consumers when promoting events. The more granular the data, the more Fever can charge others to access its audiences, whether that’s for online campaigns (i.e., Secret Media Network) or experiential activations.

Strategic Arenas

With its ecosystem firing on all cylinders, Fever has turned its attention to the most fertile testing grounds for its model. Two in particular have become central to its growth story: sports and music. Here, I’ll cover its efforts in each, why these two industries were the best possible match for the company’s offering, and what I believe is the greater opportunity at play.

Sports

Fever is an exclusive ticketing partner to a growing list of prominent sports organizations. These include FC Barcelona, LIV Golf, and IFEMA MADRID, the operator of Madring, where the Formula One Spanish Grand Prix is set to take place starting in 2026.

However, these deals expand beyond just ticketing and into areas like demand generation and on-location fan engagement. For example, while the main goal of the FC Barcelona partnership is “to facilitate buying match tickets, tickets for events and all types of experiences related to the Club”, the two entities also aim “to improve the spectator experience [...] through a wide offering of events, activities, and other exclusive content.” On a similar note, Fever’s recent fundraising announcement stated that Fever is now exploring opportunities to work with the New York Mets (owned by one of its newly added investors) “to further enhance fan engagement through experiences.”

Not content with remaining in the background as just a service provider, in recent years, Fever has also started aiming for a more visible type of partnerships. As part of its short-lived deal with Chelsea, its branding was meant to appear on the kits of the club’s men’s, women’s, and academy teams. In March this year, it became the official front-of-shirt partner to Bristol City. In July, a sponsor to French rugby club ASM Clermont Auvergne. The list goes on.

These two types of deals serve very different purposes. In the first case, Fever acts as a vendor — a prominent and comprehensive kind of vendor, but a vendor nonetheless. As such, the company is being paid for the services it provides to a club; the more of those services are included in the deal, the greater the revenue. In the second case, Fever is a sponsor. As such, it’s the one paying for the right to be featured on a club’s various brand assets — the Chelsea placement, for instance, was valued at between €6M-€8M. The goal here is to convert a club’s fans into consumers of its own products and experiences, awareness into adoption.

Some deals may opportunistically blur the lines between these two formats. Beside its role as a sleeve sponsor, Fever was reportedly meant to “offer access to Chelsea benefits and experiences through an exclusive page on its events platform.” Similarly, Fever is not only Bristol’s front-of-shirt sponsor but also its official “ticketing and experience partner.” As the company doubles down on sports, it’s likely that it will continue to experiment with different roles and levels of involvement to optimize for varying business goals.

Music

While Fever has been making strides in sports, its track record is mostly in music, where it has partnered with prominent music promoters and venue operators. In addition to the aforementioned Primavera Sound, Cercle, and Pitchfork Music Festival, the recent acquisition of DICE significantly boosted Fever’s roster, with clients now including Spotify, Redbull, and Amazon Music Live. In July, Fever also announced a multi-year strategic partnership with promoter TCE Presents and premium venue operator Broadwick Group to “power” the NYC-based Brooklyn Storehouse. The agreement “designate[d] Fever as the primary ticketing and audience growth partner for all events at Brooklyn Storehouse” as well as all of TCE’s events in New York.

Up to this point, this playbook doesn’t look too different from the one pursued in sports. Fever appears to be focused on landing large accounts that can ensure substantial business thanks to either the frequency (e.g., Cercle) or the sheer size of their events (e.g., Pitchfork Music Festival). As in sports, it also seems to be seeking increasingly comprehensive partnerships that will enable it to deploy more and more of its solutions. For example, its role as an “audience growth partner” to TCE and Broadwick Group will likely leverage Secret Media Network.

Where Fever’s approach to music differs from its strategy in sports is through Fever Originals. Rather than solely serving clients, as it does in sports, Fever also produces and operates a growing slate of its own music-related experiences. Today, these include:

We call it, a series of live music shows celebrating specific dance styles (e.g., tango, flamenco) and music genres (e.g., jazz, cabaret)

Ballet of Lights, a glow-in-the-dark ballet show that’s itself a spin-off of the “We call it” series

Eonarium, a travelling, immersive music and light show co-produced alongside Zurich-based artist collective PROJEKTIL

Monitoring this portfolio can be tricky. What is known as Ballet of Lights in Paris and Stockholm is We call it Ballet in Lisbon. Meanwhile, We call it Jazz only exists as the New Orleans-inspired The Jazz Room on the Fever marketplace. Temporary partnerships may also overlap with more evergreen offerings: for example, Authentic Flamenco — a co-production with Teatro Real and SO-LA-NA — is not to be confused with the fully Fever-owned We call it Flamenco. Overall, Fever’s portfolio appears to be in a state of constant experimentation, with concepts alternatively expanding or spinning off to match demand while maximizing brand recognition.

Among all these experiences, a few stand out. As I explained in “The new spectrum of music shows”, Candlelight has become a poster child for Fever’s editorial vision, business strategy, and operational savvy. Already a thriving consumer business, the format took another dimension with the launch of the enterprise-focused Candlelight for Business. With fairly similar requirements in terms of venues and talent, We call it now appears the most likely to follow the Candlelight playbook.

Fever has also ventured into much larger-scale events. Spain’s Polar Sound festival has been running since 2019. In France, the company now runs both Initial, an electronic music festival whose fourth issue took place in Bordeaux in late August, and the freshly launched hip hop festival Hypnotize. Elsewhere, the startup has experimented not only with the aforementioned Eonarium but also the transparently named DroneArt Show — “a unique fusion of drones and live classical music.”

As with sports, these two categories contribute to Fever’s goals in different ways. Smaller, more intimate formats like Candlelight and We call it are highly scalable and, when successful — which these two specific series certainly are —, serve as cash cows to fund the rest of the business. By contrast, large-scale events like Initial and DroneArt Show stand out as these high-stake, high-impact experiments in which Fever gets to push the envelope of what live entertainment can look like.

Perfect playgrounds

Despite tactical differences in how Fever has approached them, sports and music share a few traits that make them both a perfect match for the company’s vision and offering.

Scale

In “The new spectrum of music shows”, I pointed out how the blockbuster concert era is starting to show cracks, as ticket inflation and market saturation push more and more consumers to choose more selectively who to shell out for. That being said, large-scale events continue to make bank. According to Pollstar, arenas accounted for 49% of tickets sold and 52% of gross worldwide live music revenue in 2024. Smaller venues including theaters, amphitheaters, and clubs collectively accounted for the remaining 34% of tickets and 25% of revenue. The largest music festivals like Coachella, Las Vegas’s EDC, or Montreal Jazz Fest are well over the 500,000 mark.

Meanwhile, sports essentially runs on scale. In the US, average match attendance during the 2024-25 season was 18,147 for the NBA, 40,421 for the English Premier League, and 69,555 for the NFL. And that’s before even mentioning so-called mega-events such as world cups, Grand Prix races, or the Olympics, which routinely draw crowds of millions.

Simply put, celebrations such as these represent tremendous business. For Fever, being the exclusive partner to a top festival or a sports team and its home stadium ensures not just considerable but also recurring volume. Instead of having to heavily promote a myriad of smaller third-party events, the company can confidently lean on its partners’ unique pull. And that’s only existing demand — as recent deals show, Fever is increasingly involved in helping its partners grow their reach. Finally, landing large, prestigious clients also has tremendous benefits in terms of brand recognition and legitimacy, streamlining future business development efforts across every industry.

Stadium experience

Stadiums and arenas are no longer satisfied with serving as mere containers for a single show or match. Owners now treat the main event as the centerpiece of a longer narrative designed to keep visitors on-site, engaged, and spending as early and as late as possible. In sports, the Savannah Bananas offer a textbook example. Each game — the team calls them “shows” — is preceded by Pre-Game Plaza featuring live performances and player and “cast” appearances, and followed by a DJ-led after-party that encourages fans to linger. Beside entertainment, each segment adds fresh monetization touchpoints without inflating the ticket count.

That temporal stretch is matched by an aggressive re-imagining of the venues themselves. Owners are turning both their interiors and surroundings into multi-use experiential and commercial zones designed for year-round activation. Sports organizations everywhere are entering public-private partnerships that anchor their stadiums into entirely new districts and expand their commercial and cultural footprints in-between match days. In North America, 37 projects of at least $1 billion, each linked to teams in the five major sports leagues, are in various stages of planning. These districts capitalize on a full calendar year of events, reach a net-new and more diverse audience, and create new inventory for advertising and sponsorships, flattening sports’ usual seasonality and stabilizing cash flow.

For Fever, this evolution is a boon. By expanding beyond ticketing and into fan engagement, the startup profits not just from the main-event ticket purchase but also from all the adjacent monetization opportunities. Accordingly, its partnership with IFEMA MADRID will include “immersive fan zones, live entertainment and city-wide experiences” spanning “concerts, DJ sessions, live shows and other special performances.” The more diversified a partner’s offering, the more reasons fans have to come back and spend time and money, the more transactions Fever gets to take a commission off and the more revenue it can generate. Its cashless wristbands and mobile wallets accelerate checkout speed, push average order value higher, and generate granular transaction data that can be re-routed into its marketplace or Secret Media Network for precise audience targeting. In short, as stadiums grow more experiential, Fever evolves from ticketing gateway to revenue engine for everything that happens before, during, and after the headline act.

Superfans

Both sports and music are notorious for the level of engagement they can spark. Over the years, event organizers across these sectors have learned to better identify and cater to so-called superfans — the highly engaged, high-spending fans hungry for access and exclusivity.

In music, this segmentation is still done somewhat rudimentarily, primarily through pricing. Festivals big and small have for years offered VIP packages, with perks including fast-track entry, premium lounges and viewing spots, better food options, and more. In 2025, a VIP pass at Coachella will set you back roughly $1,200 inclusive of fees, about double the price of a general admission ticket. While these upsells are certainly margin-additive, they ignore the non-monetary forms of engagement that are so essential to artists’ long-term success.

In comparison, segmentation in sports seems light years ahead in terms of both comprehensiveness and granularity. All prominent sports teams and organizations now run extensive loyalty programs that enable them to measure and reward every level of fandom. These programs enable fans to engage beyond just transactions and through a multitude of activities, whether digitally or in-venue. In exchange, members of Club Maverick or NASCAR’s Fan Rewards receive a variety of perks, from discounts and cashbacks to early access to members-only experiences. Revenue is secondary: being free to join, these programs prioritize long-term engagement. Fans are incentivized to complete their profiles in order to access personalized content and offers, further enriching these organizations’ understanding of their communities.

For Fever, the growing focus on superfans is a huge opportunity. As a ticketing provider, the company stands to benefit the most from premium purchases. By plugging into its partners’ increasingly refined view of their audiences, it can dramatically improve its targeting and conversion rates for both its partners’ offerings and its own.

Additionally, there’s a clear white-space opportunity for Fever to build — or enable — loyalty infrastructure across its ecosystem. While the platform has so far focused on one-off purchases, the recent launch of the subscription-based Secret Club marked a first step toward more durable customer relationships. This logic could be extended further, either through Fever-branded loyalty programs or as a white-label feature offered to partners. Precedents already exist: Ticketmaster is an official partner of Audience Rewards, Broadway’s points-based loyalty program, which incentivizes repeat purchases and helps organizers consolidate audience data in an otherwise fragmented landscape. For Fever, a cross-vertical rewards system would unlock new levers for retention and cross-selling.

Sponsorships

Ticket sales may be the primary way event organizers make money, but it’s far from the only one. Today, sponsorships represent a substantial and high-margin revenue stream for both sports and music organizations.

This fact is especially prevalent in sports. From the Golden State Warriors’ pre-sales newsletter (presented by Ticketmaster) to the Lakers’ mobile app (presented by bibigo), there isn’t a single brand asset in professional sports that’s not for sale. The same is true of the venues. Beside venue-level naming rights, high-traffic areas like entryways, parking lots, and concessions are increasingly being turned into brand activation zones by displaying sponsored signage. NBA teams collectively earned a total of $1.62B in sponsorship revenue during the 2024-25 season, up 8% from the previous year and 91% from the $850M earned five years prior. Importantly, this growth was driven not by more deals — deal volume grew just 2.5% year-on-year — but by the number of assets included in each deal, signaling a move toward more comprehensive partnerships.

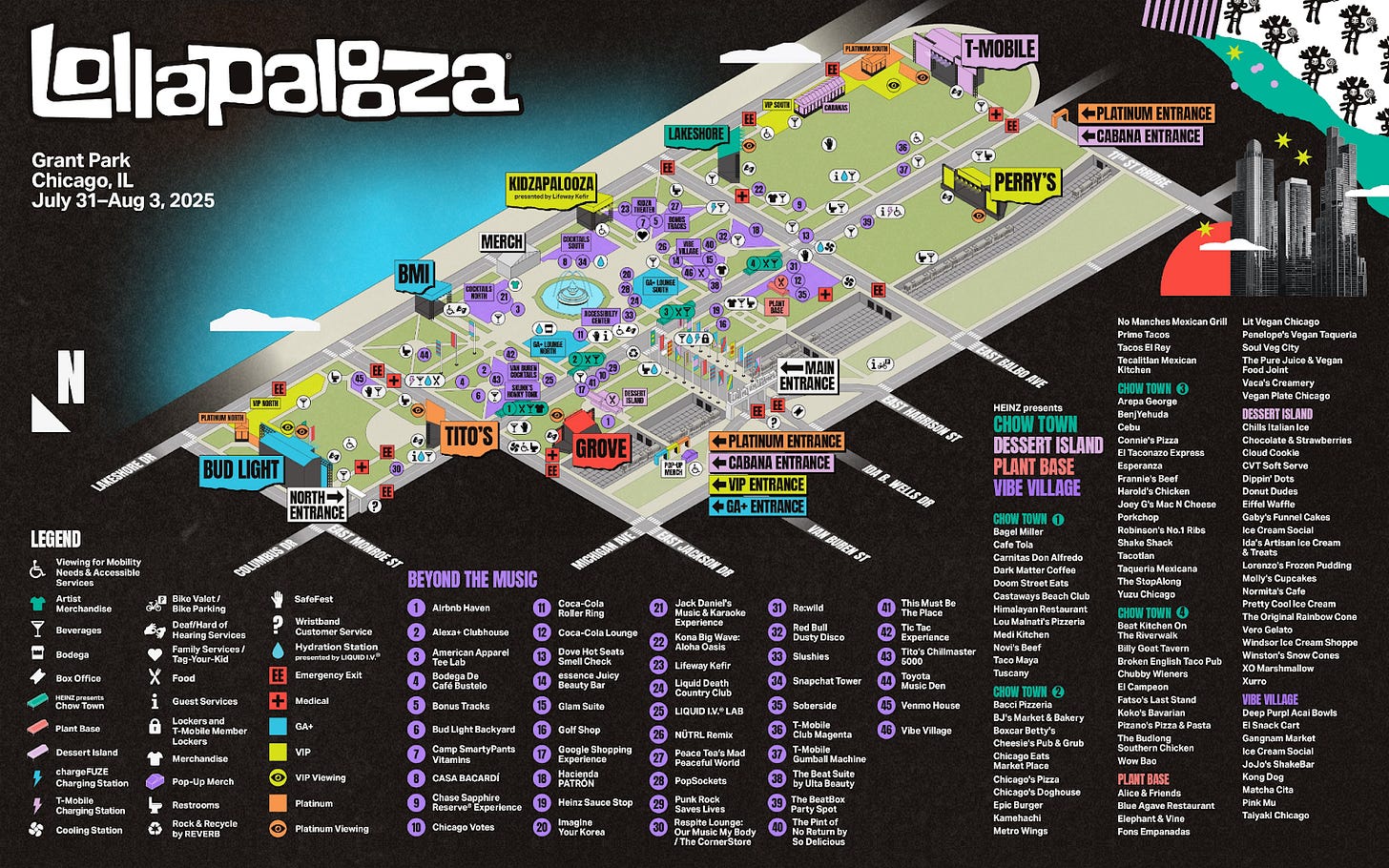

Meanwhile in music, sponsorships have been a lifeline for many festivals. Today, they take many forms, including naming rights (e.g., the mouthful that is “American Express presents BST Hyde Park”, in London), online and in-app advertisements, exclusive partner rights (e.g., Airbnb x Lollapalooza), and on-site signage and brand activations. In 2025, the Berlin edition of Lollapalooza had no fewer than 22 different sponsors across categories.

In this context, Fever’s own established relationships with brands seems like a perfect match. Today, the company already interacts with advertisers through both Secret Media Network (for brand content and digital campaigns) and Fever for Business (for custom events and perks). By partnering with venues and event organizers through either ticketing, Fever Cashless, or both, it now has access to high-value real-estate it can make available to brand partners. Importantly, Fever’s operational prowess and expertise in experiential marketing allows it to go beyond just signage and instead develop the kind of truly engaging and memorable activations that fans crave and premium brands will pay big money for. The IFEMA MADRID announcement, for instance, suggested that Fever “may also produce parallel events across Madrid,” including brand activations.

Sports and music are more than just verticals for Fever: they are laboratories where the company can stress-test its capabilities at scale. From ticketing to payment systems and from event production to brand activations, each piece finds sharper relevance in these industries because the audiences are massive, the fandom visceral, and the willingness to pay virtually limitless.

What’s Next

Fever is delivering on its original vision. Whether it be its portfolio of Originals or Fever Cashless, it continues to find new ways to engage and monetize, all the while generating the data and insights that can inform its strategy, refine its products, and improve profitability. As the company enters its next chapter of growth, it will find no shortage of opportunities, but also new risks that may test the resilience of its model.

Opportunities

Doubling down on immersive

Fever’s track record in immersive entertainment is undeniable. On the ticketing front, it has partnered with some of the industry’s most prominent players, including Exhibition Hub, Culturespaces, and Moment Factory. As these companies continue to develop new concepts and deploy them around the world, Fever as their ticketing provider, promoter, or both, gets to build off their brands and grow alongside them. Meanwhile, on the events side of the business, virtually all Fever Originals have emerged from the genre.

As it enters its next chapter of growth, Fever should double down on the category that has served it so well. This means not just keeping what’s working, but also identifying and locking in the most promising concepts before someone else does. Companies like Sweden’s Prison Island, Croatia’s Paradox Museum, and France’s Science Experience and SENSAS — all of which Fever has already signed — have made no secret of their ambitions and continue to expand across territories thanks to efficient franchise strategies. Somewhere around the world, small, resourceful teams are already iterating their way toward the industry’s next blockbusters; finding them should be a top priority.

To my knowledge, Fever currently either develops concepts in-house or partners with third-parties to help them scale their businesses. But as immersive entertainment continues to mature as an industry and an asset class, I believe the company may begin to act as more of a financier, opportunistically acquiring promising concepts at the earliest stage to fully capture the upside or, conversely, divesting proven franchises at high multiples once they’ve reached their potential.

One last opportunity lies in finding synergies with more of Fever’s activities. Fever Cashless seems like a primary candidate in that regard. Compared to large-scale manifestations like music festivals and sports events, location-based entertainment franchises are unlikely to need capacity control or inventory management, but they likely have challenges of their own. Can Fever’s software help eliminate workflow bottlenecks and reduce “days-to-dollars” for new openings to improve both location-level and franchise-level profitability? Can its network help operators find local talent, source vendors, or license content? The more invaluable the company can become to immersive entertainment specialists, the greater the opportunity.

Industry diversification

Fever’s focus in terms of business development has been on landing large partners whose business can bring it scale and legitimacy. While sports and music have received most of the attention so far, a little LinkedIn sleuthing and the company’s job board show it has set its sight on a third industry: culture.

A number of factors make this space an attractive target. At a high level, it fits Fever’s ambition to make all of culture available on its platform. But there are more practical arguments, too. Collectively, cultural institutions receive dozens of millions of visitors every year, meaning just as many tickets for Fever to take a cut off. Despite fragmentation — the International Council of Museums estimates there are at least 55,000 museums worldwide —, the top institutions garner the most of the volume and revenue: in 2024, total attendance across the top 10 museums amounted to over 51 million visitors, with Le Louvre alone accounting for 17% of that total. This distribution means that here, too, Fever can focus on a small number of deals to generate appreciable revenue.

Compared to industries like music and sports, much of the museum world also lags behind when it comes to digital readiness. Years (or decades) of technological debt, together with limited budgets, have hindered institutions’ ability to collect and monetize insights about their visitors. This is despite them being increasingly dependent on earned income — as opposed to the public subsidies that have long kept them afloat. In short, Fever is finding in culture a large, global, under-digitized market eager to adopt any solutions that can help it become more efficient and profitable.

It’s worth noting that Fever isn’t starting these conversations from scratch. Original concepts like Candlelight and We call it routinely take place at some of the most prestigious cultural locations. By renting their available spaces for its own use, Fever has already established valuable relationships with many of these institutions. Additionally, it has always presented these formats as a way for them not only to generate revenue but also to engage younger audiences. In short, Fever’s events activities have already enabled it to demonstrate goodwill toward the industry; they can now serve as a wedge to take over more of these partners’ operations, from ticketing to inventory management.

Margin-additive ticketing

Fever’s wide-ranging “marketing fee” has already enabled it to move away from the traditionally low margins of the ticketing business. Still, a few additional monetization levers could help it take this activity to the next level.

The common denominator is event desirability. The more exceptional the event, the more options it unlocks: fans will pay up for perks, tolerate price adjustments, and usually find happy buyers for their seats if they somehow can’t make it.

Fever’s portfolio of Originals has arguably been designed to avoid frenzy. Scalable, evergreen, and available across dozens of cities, formats like Candlelight simply don’t spark the scarcity-driven behaviors that make upselling, dynamic pricing, or reselling truly lucrative. But as the company expands its roster of IP-backed shows and major partnerships, those tools may find new relevance.

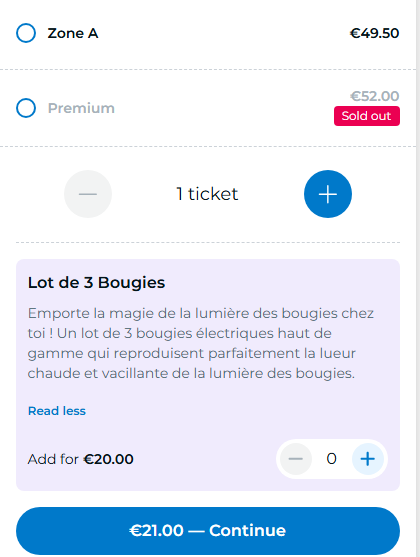

Upselling

The more exceptional the event, the more willing consumers are to splurge in addition to what they see as the base price. For event organizers — and, by extension, Fever as their ticketing provider —, this unlocks new opportunities for monetization.

Upselling comes in many shapes and forms. These days, tickets can be profitably bundled with everything from merch to food & beverage vouchers, parking passes, and more. For example, Ticketmaster offers “upsell opportunities, curated travel packages, digital collectibles, and more.” Combined, these options can contribute to a material uplift: 58% of Ticketmaster users have purchased an add-on of any kind, with the average incremental spend amounting to an impressive $300.

Travel and accommodation appear particularly promising as a category. In the U.S., actual ticket cost accounts for only a fraction — 24% on average — of the total cost of attending a concert, far behind accommodation at roughly 38%. Bank of America found that half of respondents (50%) have traveled out-of-state and/or internationally to attend a concert, sporting event or festival in the past two years; 41% of Gen Z and 44% of Millennials have flown within the U.S. to attend one such event. The trend shows similar numbers in Europe. Dedicated players like Vibee are now catering to the so-called “gig-tripping” crowd with exclusive packages that include hotel stays, complimentary entry at local attractions, themed gift kits, and more. The more destination-worthy events Fever serves, the more relevant these extras will become in the purchasing journey.

Reselling

From a consumer’s perspective, reselling is a valuable feature to have no matter what. Anyone who, for some reason, can no longer go to an event they had every intention to attend — in other words, anyone who’s not a professional reseller — will usually be glad to find an easy and secure way to break even from the same place they made the original purchase.

While they may swear that this is all about convenience, the platforms certainly benefit too. One recurring complaint against ticketing providers is that they essentially “double-dip” by charging fees on top of both the initial and the secondary sale. Big or small, any resale is a positive when you’re getting a cut.

Still, the upside only reaches its full potential with the most in-demand of events. In its 2024 annual report, Live Nation noted that “in states where resale caps aren’t allowed, average resale prices are 2x higher — with some markups reaching 10 to 50 times face value.” Because the fees its charges on each transaction are proportional, Ticketmaster profits most when prices are the highest. For example, the service charge for one standing ticket to see Oasis in Manchester was £53.48, or 15% of the resale price of £357.95. Artists or local legislation may at times impose caps on resale price, but the platform can still make a hefty profit in the aftermarket.

As far as I can tell, Fever doesn’t currently enable reselling — as mentioned, most of its portfolio doesn’t call for it — but as it onboards more partners and their “can’t miss” events, the company will have the perfect excuse to implement it. What remains to be seen is what it will make of this opportunity. DICE, which Fever acquired in June, has been praised by consumers and promoters alike for its Wait List feature, which enables fans to resell their unused tickets only at face value to get a full refund. While this pricing policy is certainly fan-friendly, the prospect of a real markup may be too compelling to pass on for long.

Dynamic pricing

The continued rise and professionalization of reselling is proof enough that event organizers and their providers are still leaving a lot of money on the table. Rather than let scalpers siphon up the upside after the fact, platforms have been working on capturing willingness to pay at the source. Dynamic or “surge” pricing — the practice of having ticket prices adjust to demand in real time — has been a primary tool in this strategy.

Live Nation has long been among the model’s primary proponents and beneficiaries, as its emphasis on the higher tier of venues and events made it an ideal target for scalpers early on. In February 2024, Live Nation CEO Michael Rapino described the practice as the company’s “great growth opportunity,” as the system gets rolled out in more countries, is implemented more systematically, and trickles down to mid-tier venues.

As with reselling, the very nature of Fever’s portfolio has arguably made it ill-suited to dynamic pricing. Nevertheless, the feature is listed among its “event management capabilities”, a sign that it might be an important selling point for its partners. Though I haven’t been able to see it applied in the wild, the marketplace already includes a “Selling fast” category, which is where this kind of feature would make the most sense. As the company takes on more one-off spectacles and event scarcity becomes more crucial to its business, it should be able to monetize demand spikes accordingly.

Sponsorships

I’ve discussed earlier how Fever strategically turns single experiences into fully-fledged entertainment platforms, improving their range, repeatability, and business potential. With Fever for Business, it now makes its portfolio available for every corporate occasion. But there’s another key modality in which third parties can engage with the company’s roster: sponsorships.

Possibilities abound. On its website, Fever lists options that include on-site branding, product placement and distribution, and, as always, the ability to amplify the partnership digitally through a Secret Media Network campaign. The Bridgerton-themed Queen’s Ball featured Lindt chocolates, while a Candlelight concert was sponsored by Brazilian craft beer brand Baden Baden. On the platform, an ABBA-themed Candlelight concert in Paris was apparently sponsored by the perfume brand Nina Ricci. In total, a dozen Originals are already up for such activations.

The business case is obvious on both sides. For brands, these deals are an opportunity to engage young, urban, and affluent audiences across premium moments — which also happen to generate copious amounts of user-generated content — in order to create lasting positive associations. For Fever, they add another layer of revenue on top of ticket sales. Interestingly, sponsorships are also available for IP-backed experiences like The Magic Box (with Disney) and Harry Potter: A Forbidden Forest Experience (with Warner Bros.), a sign that Fever isn’t afraid to monetize the same event twice. With this strategy, every experience becomes a high-margin stackable asset.

Experiential layer

I’ve highlighted earlier how RFID adoption through Fever Cashless can enhance event operations for consumers and organizers alike, while also surfacing valuable insights into participants’ on-site behavior.

Still, I believe Fever is after more than efficiency gains or data: its own events suggest that it’s trying to create an entirely new experiential layer on top of the physical one. The last edition of Initial, for instance, came with a new identity and marks the beginning of “Mission Saturne”, an “intergalactic journey where music and space come as one” and “an immersive experience that extends beyond the festival.” While details remain scarce and this could be only marketing parlance, such language suggests big plans around worldbuilding and gamification.

There are precedents for this: some of the world’s largest players in live entertainment have for years been trying to enrich the guest experience through a mix of technology and storytelling. Disney has MagicBands, which let visitors enter its parks, pay for items, access fast lanes, and more. Another notable feature, now discontinued, was the bracelets’ integration with the attractions themselves, which would display a guest’s name as they passed by. Nintendo’s Power-Up Bands let guests collect digital coins and stamps and play interactive games. In music specifically, major festivals like Coachella have been using augmented reality for everything from navigation to brand activations.

With its expertise in immersive entertainment, Fever could turn both its own and its partners’ events into interactive experiences, with event-specific side quests and content to unlock. This would not only increase dwell time but also spark conversation both during and after the event, boosting visibility for organizers. Of course, not all events would lend themselves to this vision. Smaller venues lack the space to deploy such activations, and many artists may be wary of these activities competing with them for fans’ attention. Still, if Fever can inject even bits of its know-how into more traditional events, it will have found a unique differentiator.

Risks

The opportunity set is real, but so is the friction. As it continues to scale, Fever will expose itself to several failure points.

Execution risk

Fever has so far been able to scale without major hiccups. Yet the more global it grows, the more experiences it offers on its marketplace, the more it risks spreading itself too thin operationally.

When it comes to third-party experiences, Fever is ultimately dependent on its partners’ execution. Yet as the interface through which consumers first discover and pay for these experiences, it stands on the front line if anything happens. A poor performance, broken equipment, or a mismanaged venue, and Fever will be the first place unhappy consumers turn to to complain. The reputational risk is only heightened by the company’s insistence on having its name featured prominently on its partners’ websites: “Powered by Fever” may sound great when everything is going well, but it comes with unwanted associations if or when things go awry.

Poor integration with a partner’s systems could also cause issues. For instance, a Reddit user who bought movie tickets via Fever was later hit with an extra $6 per ticket by AMC because it happened to be an IMAX screening. This sort of confusion is sure to leave consumers disappointed and could well deter them from using Fever’s app ever again.

Despite promising greater control over the output, the company’s own experiences come with their own share of uncertainty. After all, many Fever Originals rely heavily on local musicians, performers, and small creative partners. This human factor poses significant execution risk as any visible slip-up could erode consumer trust in the overall concept or even the company at large. As mentioned, Fever maximizes replicability thanks to simple formats, repeatable programming, and streamlined processes — Candlelight artists, for instance, are vetted through an online form. Still, when operating at that scale, mistakes are bound to happen.

Ultimately, the damage is somewhat lessened by the way experiences are compartmented at the interface level. Because of Fever’s hyperlocal focus, each version of each concept in each city gets its own profile page on the platform. The Bridgerton-themed Candlelight show has one, whereas the Ed Sheeran one has another. With each variant getting its own reviews, no particular instance of a concept can drag down the others’ perception because of its ranking.

Competition

As a young company and a challenger, Fever is fortunate to be able to learn from the successes of those that came before. At the same time, it itself is not safe from imitation. In fact, because it operates across several, and vastly different, activities, competition is coming from multiple fronts at once.

On the media front, the success of Secret Media Network has already attracted attention. In July 2025, Ticketmaster unveiled City Guides, its own “curated, city-focused pages” meant “to drive event discovery and connect fans with local experiences and events” across live music, sports, theater and entertainment. Currently live for London, Los Angeles, and New York, these guides are meant to make the most of the “more than 2 million monthly Google searches for city-based event queries”, an opportunity Ticketmaster had so far largely ignored by focusing on travel-worthy rather than local entertainment. While it has a long way to go to catch up with Fever’s hyper-local media empire, this initiative shows that the strongest differentiators are also the most worth copying.

The same risk applies to Fever’s Events segment. Despite their operational demands, many of Fever’s concepts are simple enough that they could be replicated fairly easily by others, including in territories where the company does not yet operate. In this scenario, a fast-paced “copycat” strategy could preempt high-prized cities or even entire countries before Fever has had time to settle in. In locations where Fever is already established, any competition would inevitably increase customer acquisition costs, hindering the profitability that today is one of the company’s markers.

As for ticketing, the space is notoriously crowded. Companies like Vivid Seats, SeatGeek, StubHub, and others have been lurking in Ticketmaster’s shadow for years. Another upstart, France’s Shotgun is currently making strides in the US after first focusing on Europe. All these players are hard at work to lock the most valuable event organizers and IP into long-term contracts, leading to a game of musical chairs in which success is achieved not by growing the pie but by displacing a predecessor. And competition keeps growing. As mentioned, companies like Vibee and Quint — a property of Liberty Media, itself a major shareholder in Live Nation — are going after the most affluent fans with exclusive experiential packages.

Simply put, Fever is poised to face increasing challenges across the entirety of its business.

Brand fragmentation

When it comes to branding, Fever’s strategy is subject to two contradictory forces.

On the one hand, the company’s brand building has grown more deliberate over the years. Today, this vision manifests in a number of ways. The first one has to do with how the company enforces brand consistency across its many properties. The websites for its original concepts, as well as many of its partners, all visibly draw from the same template, from their influencer-filled hero videos to their structure, copywriting, and fonts. The company’s name is visible no matter what: Originals are “Presented by Fever” or “An original experience by Fever”, while third-party experiences are “Powered by Fever.” Second, Fever’s recent involvement as a sponsor in sports attests to its ambitions around becoming a true consumer brand rather than a nondescript service provider. The acquisition of DICE, with its recognizable brand identity, was another step in that direction.

On the other hand, the sheer breadth of Fever’s portfolio runs almost counter to those efforts. While Fever’s original experiences can all be loosely described as “immersive”, they still span a wide spectrum of concepts — individual or group activities, quiet or active, technology-enabled or not. This eclecticism is further heightened by these concepts’ respective brands. Candlelight, for example, has by now taken a life of its own; We Call looks well on its way to do the same. The more awareness these individual experiences attract, the less Fever as the umbrella company seems to matter in the consumer’s eyes.

Granted, there are still synergies to be found, for example, by bundling together experiences with somewhat similar concepts or shared traits — the music-centric Candlelight and The Jazz Room or the dance-related Ballet of Lights and We Call it Tango. Going beyond recommendations, it could also offer discounts for specific packages as a way to steer consumers toward experiences they might otherwise not have considered. Such a strategy would be especially valuable for kickstarting demand for newly launched concepts. It could also be used to regularly boost basket size across the entire marketplace. In 2025, July 22 and 23 were declared “Fever Days,” during which consumers could enjoy “48 hours of epic discounts” on the top experiences in their cities — most of which, conveniently, already happen to be Fever Originals.

The biggest risk of brand fragmentation is in how it prevents the company from creating precisely the sort of synergies that make for the strongest and more durable engagement: narrative ones. In immersive entertainment, Meow Wolf is now tying its various installations together into a single creative universe. This encourages its most passionate fans to visit one location after the next in order to compare experiences and gather more of the company’s lore. In comparison, Fever is only able to expand on a concept through discrete variations — e.g., The Jazz Room’s soul version — rather than narratively.

Parting Thoughts

Fever appears to be on the right track. From its humble beginnings as yet another ticketing provider, it has grown into a multifaceted business that now produces and monetizes culture at lightning speed and industrial scale.

Underpinning this success is an ever-growing stream of data flowing from both digital and physical touchpoints, which the company then methodically leverages into new offerings. The result is a highly holistic system in which each new business line works in lockstep with the rest. Data brings out local demand and helps prioritize deployment. Media drives sales. Events make room for brand activations and are streamlined with cashless payments, generating deeper insights into industry workflows and consumer behavior. B2C opens up to B2B. Across all those initiatives, the benefits are compounded by a focus on operational excellence and profitability.