A Playbook for Playful Publishing, Part III

The Playbook

Hi there! I’m Maxime, and you’re reading Recreations, a newsletter about the intersection of media, technology, and culture.

You’re receiving this either because you subscribed or because someone forwarded it to you. If you’re in the latter camp, you can subscribe here or via the button below.

Welcome back to another installment of A Playbook for Playful Publishing.

In Part I: The Promises and Trappings of BookTok, I unpacked BookTok’s workings, why the platform might have looked so appealing to publishers when it emerged, and why its ever-growing influence actually threatens the industry’s long-term prospects.

In Part II: On Judging Books (and Publishers) by Their Covers, we explored exactly why we care about a book’s cover so much, what messages it sends and to what purpose, and why its pull has never been stronger.

This is Part III: The Playbook, where I lay out five interconnected strategies that publishers can explore to generate engagement and revenue and to grow awareness beyond individual IPs and toward their own brands.

Up next is Part IV: Monsieur Toussaint Louverture: Publishing as Craft, where I’ll dive deep into Monsieur Toussaint Louverture, a French publisher whose opinionated curation and attention to detail represent the best of what indie publishing can be.

If you haven’t already, make sure to subscribe so you get this last installment straight into your inbox.

Thinking Past BookTok

In the first part of this series, I made the case that the publishing industry's reliance on BookTok is a ticking bomb. Let's recap the argument.

In the four years since the community started to take off, publishers have come to lean on BookTok for everything from market research to content acquisition, discovery, promotion, and sales. Despite their best efforts, they have submitted themselves to continued commoditization. BookTok's wariness of corporate messaging prevents publishers from marketing their titles themselves and pushes them instead to go through "bookfluencers" who have no real incentive in the success of any particular book.

Meanwhile, the platform's feed-first experience means publishers have no stable digital home that they can build to their image in order to embark readers onto a fuller experience. Last but not least, under the pretense of supporting authors and publishers, TikTok has been encroaching on more and more of the industry's value chain. The company is now not just a major influence on discovery (especially among young readers), but also a retailer (through TikTok Shop) and a publisher in its own right (through 8th Note).

Individually, none of these points should be cause for too much concern. But they do add up. All in all, publishers have put themselves in a precarious position.

On the one hand, it's clear by now that they are not thriving on the platform — even though their books, and the influencers who promote and live off them, might be. On the other hand, BookTok is now so central to their business that they can't afford to disengage overnight. Years ago, in a very different industry, cosmetics company Lush became "anti-social" and deleted its accounts across all the major social platforms. At the time, Lush had a beloved consumer brand, dozens of stores of its own and, I presume, what must have been a solid CRM. Book publishers, meanwhile, have none of that, and therefore, no clear plan B.

But pointing out the problem is the easy part; what publishers need are solutions.

For that, we need to go back to what pushed them to so naively embrace TikTok’s disruption in the first place. Namely: structural reliance on intermediaries and, as a result, weak brands that have hindered their ability to engage and monetize readers in novel ways. Only by overcoming these issues can publishers stand on its own.

Here, I'd like to explore five interconnected avenues that I believe can help them regain control of their destinies. Crucially, I want to focus on strategies that can succeed with or without BookTok — strategies that would certainly benefit from building off it for amplification, but can bring value regardless. After all, if platform dependency is the problem, the solution can't possibly be to double down; publishers need to play to their own strengths.

This is the Playbook:

Going deluxe

Doubling down on merch

Experiential storytelling

Mastering eventization

Bringing back the serial

Now let’s get to it.

A Playbook for Playful Publishing

Going deluxe

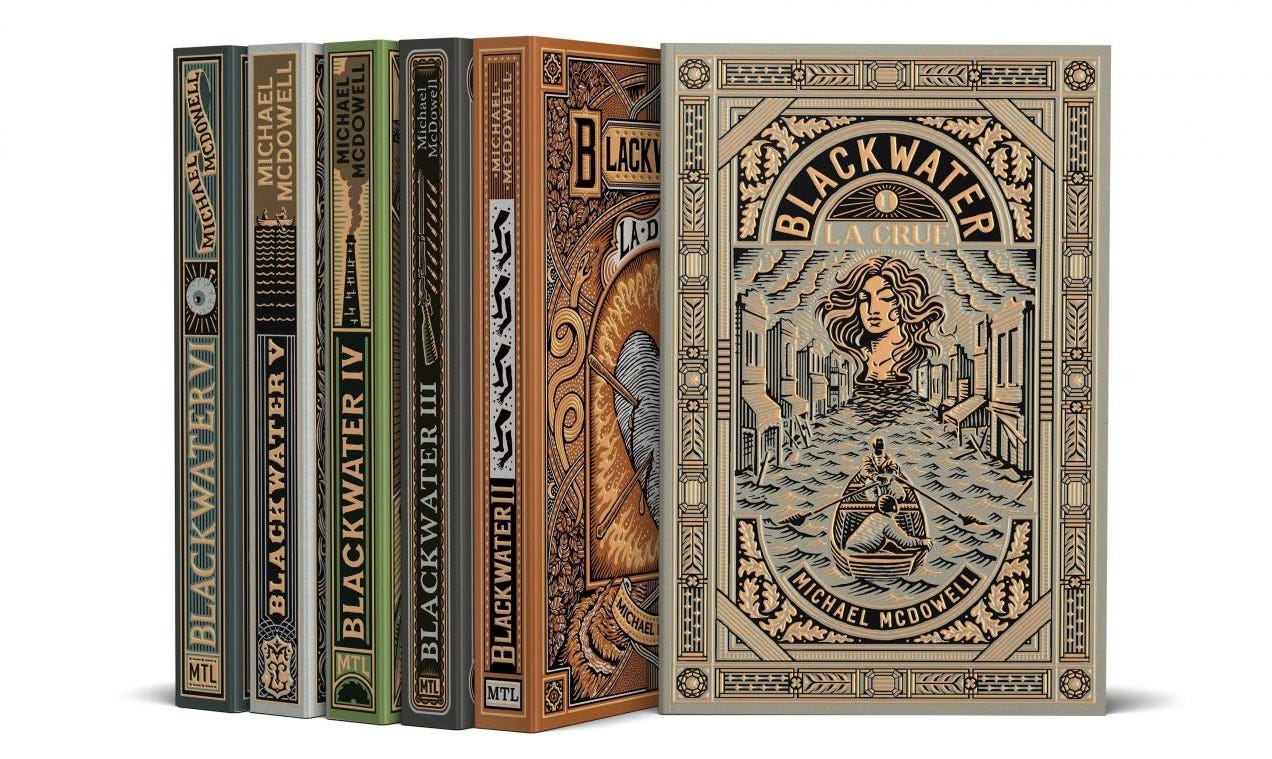

It may be hard to fathom in the ebook era, but books weren't always so fungible. Centuries ago, back when publication depended on royal or religious approval (read, censorship), it was the custom for publishers to thank their patrons with luxury versions of their books. These copies were produced in larger formats — hence their nickname of "grand papiers," French for "great papers" — with wider margins and higher-quality paper types that allowed for finer prints and more comfortable reading. Censorship and the need for patronage eventually ended; "grand papiers" stayed. Now reserved for the publishers themselves, authors, and select individuals, they were meant to stay out of circulation. However, there's nothing people want to buy more than something they're told is not for sale, and it didn't take long before bibliophiles started seeking these copies specifically.

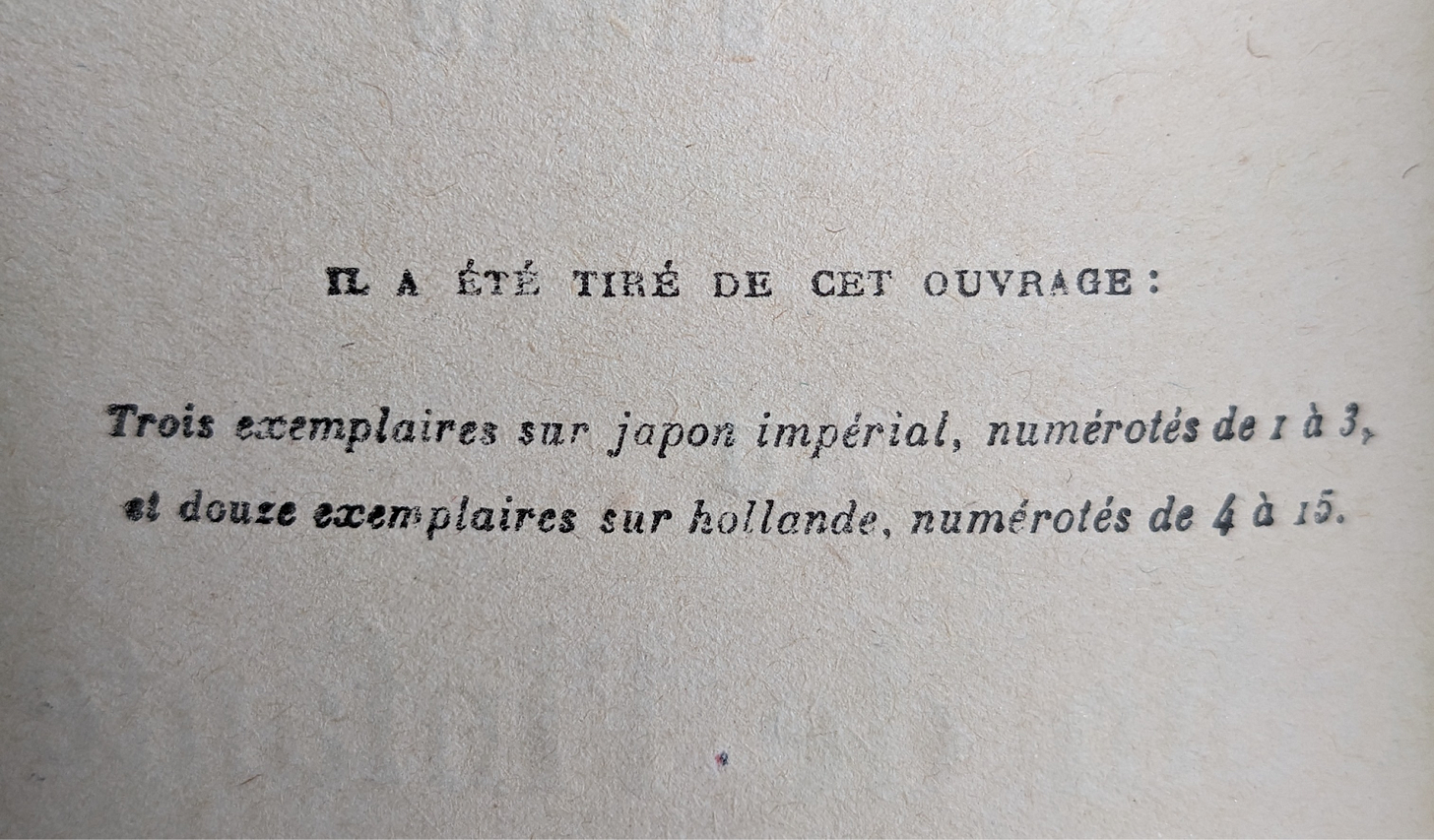

At the end of the 19th century, technical advancements dramatically improved the output of the printing press. Mass production lowered costs, then prices; books became a commodity. To differentiate from mass market prints, publishers started using luxury editions in a more systematic and strategic fashion. "Grand papier" turned into a small but lucrative business — the smaller the batches and the finer the paper, the higher the price of a book. In interwar France, it wasn't uncommon to see a novel debut on a dozen types of paper, in batches ranging from a few thousand to as few as three copies.

Very little of this tradition remains today. As the industry continued toward mass production, production time and material costs — in 2005, a single sheet of Japan paper cost 15 euros — made these editions increasingly unviable. The manual adjustments required to produce them slowed production and represented an opportunity cost for printers. Whereas "grand papier" prints used to be printed first, they were now printed last, if at all. The vicious circle was in full swing. The fewer deluxe editions came out and the less publishers promoted them, the smaller the market. With the advent of film, reading slowly but surely lost its seating in the cultural hierarchy, and the book as an object lost its luster. Today, only a handful of publishers are keeping "grand papier" alive — partly as a nod to the old days, and partly to attract those few authors who still care, or even know, about the practice.

It's time to revive it. As I wrote last week, the Venn diagram between BookTok and book collectors is almost a perfect circle — there is a reason why the community’s flavor of reading is often derided as performative. The way books look and feel, what materials they’re made of, how well they pair together on a shelf, all these things are central to how reading is practiced and, more importantly, staged on the platform. Whatever you may think of these consumeristic impulses, they signal real shifts in reading culture. Together, shelf aesthetics and what I’ve called readers’ longing for analog are the perfect excuses for bringing luxury to the book world.

For publishers, a luxury strategy brings two potential benefits: monetization on the one hand, and engagement on the other hand.

Let's start with monetization. Produced in deliberately low volume, with paper types of varying quality and price, "grand papier" prints are publishers' best shot at customer segmentation through price discrimination. In contrast with the paperback vs. hardcover dichotomy, these editions aren't about practicality or solidity but about prestige and aesthetics: they're an opportunity to draw out and engage the collector that, if BookTok is to be trusted, secretly lives inside every reader. Other parts of the creative industries — music with vinyl, film with the revered Criterion collection — can attest to the merits of this strategy.

Still, it's crucial to meet expectations. Indeed, readers are growing wary of publishers overusing the same aesthetic lures to squeeze a quick buck from them. (“Every book has sprayed edges now”, someone complained on Reddit.) Like the “grands papiers” of old, modern luxury editions will need to ensure both quality and scarcity. This will necessarily impact the strategy’s revenue potential: whatever price these prints go for won't change the fact that sales volume remains insignificant.

Which brings us to engagement. Ultimately, revenue can't be the only metric. Every fandom counts in its ranks people who make up in excitement what they lack in purchasing power. Despite not directly contributing to an artist's or company's bottom line, these fans play a crucial role inside their communities, for example by circulating important information or creating fan content. Assessing readers' involvement solely based on their willingness to pay would not only be misguided, it would be, quite literally, exclusive — the exact opposite of what we're trying to achieve here. Whether that's sending deluxe copies for free to top readers or exhibiting them for all to see, publishers should aim to draw more people in, to excite, and to inspire.

But going deluxe is not a cure-all. If they want these releases to feel exceptional, publishers should be intentional about which of their books truly call for a premium edition. Is an author's anniversary coming up? Has a book been receiving new (and, hopefully, sustained) interest online? Can publishers align their calendar with an adaptation?

A great example of the latter is France's Robert Laffont, which in 2020 published a new collector's edition of Frank Herbert's Dune ahead of Denis Villeneuve's movie release. (Villeneuve also prefaced the book, adding to the excitement.) After the first volume was released, the company continued to work on the rest of the cycle at a time when reader interest was the strongest in decades. While few books offer such opportunities, this is precisely the level of exceptionality that publishers should be striving for.

Doubling down on merch

Both culturally and commercially, the beautification of books finds its natural companion in another phenomenon: the rise of book merch. In our aesthetics-obsessed world, books and their tie-ins complement each other. Bought and unpacked together, placed on the same shelf, they have come to form a cohesive experience in the modern reader's mind.

To make the most of this convergence, astute publishers are now distributing increasingly elaborate Advanced Reader Copies (ARCs) to book influencers. For Emma Cline's novel The Guest, Random House Books sent packages that contained "a tube of Supergoop sunscreen, a box of Tate’s Bake Shop cookies, a pair of sunglasses color-coordinated to the book’s cover, and a handful of other goodies, all aptly themed around the novel, which takes place at the end of summer on the East End of Long Island." This strategy isn't limited to deep-pocketed conglomerates — with merch as with book covers, smaller publishers can make up in cultural awareness what they lack in resources. Zando, for example, has made a reputation for its cheeky publicity campaigns. Half book reviews, half unboxing videos, the content that comes out of these partnerships performs exceedingly well on social media.

While these efforts so far have been limited to promotional purposes, there is potential for more. Done well, merch directly contributes to a book's desirability — one of the key ingredients in what I’ve called the Book Cover Trifecta. By embodying characters, plots, and themes, it prolongs the reader's exposition to a narrative universe and strengthens their emotional connection with it. (Amelia Olsen, a former marketing coordinator at Zando, said "a good book box is a world-building experience that starts as soon as the package arrives at our readers’ doorsteps.”) This is especially beneficial for book series. Not only does merch serve as a token of fandom in between installments, every new book is also a chance for publishers to imagine, and readers to collect, more merch.

For publishers, this is an opportunity to think of merch not discretely, but continuously, or better: narratively. The implications are as creative as they are operational. In the same way that a series's graphic identity needs to be established from the start so it can be enforced throughout, merch should be planned with a long-term view. Going beyond tees and bookmarks, what products can publishers offer that would make up a coherent whole? How do they encourage collecting, while ensuring that readers can still join in at any time without feeling left out because they missed out on earlier items? If books and merch are two sides of a larger reader experience, it's on publishers to make it a compelling one through and through.

This is easier said than done. Merch is a hard business, and publishers already have a lot on their plates with books; taking on another logistics-intensive line of business hardly seems like a good idea. It's also difficult to ascertain this strategy's commercial potential. As both creators and brands well know, having an audience for a product does not guarantee sales. In the BookTok era, where an author's name can rack up billions of views and hashtags in a matter of months, it's easy for a publisher's marketing team to overestimate the demand for their IP. Finally, it's worth remembering that merch does not make a property's commercial success; it feeds off it. It takes strong brand affinity for a consumer product strategy to bear fruit. Save for runaway books or established series, in most cases, merch may bring only meager results.

Still, this is nothing insurmountable. Manufacturing and logistics, for example, don't have to be handled in-house. Even Disney, a company famous for its consumer product prowess, licenses its IP to third parties rather than owning and operating toy manufacturers. There is no reason why publishers couldn't take the same approach.

Assessing demand is (partly) solvable, too. Beside royalties, a licensing deal will typically include what's called a Minimum Guarantee (MG), a flat fee paid upfront by the licensee to the licensor based on forecasted sales. If a product sells better than expected (thus breaking through the MG), the licensee makes additional royalty payments to the licensor; if it sells worse, the licensee still pays the full MG. In that way, licensors minimize the downside while also maximizing the upside. With that structure in place, publishers would be financially preserved if any of their products were to bomb.

However, profitability shouldn't be the main goal here — this goes back to the monetization vs. engagement issue. As with deluxe sets, publishers should treat merch more like a wedge into readers' lives than a cash-generating business. It's about small batches, not mass production; superfans, not unknown buyers. Monetization is possible, and welcome, but obsessing over it at the expense of deeper engagement is likely to lead only to disappointment.

Further down the line, the greater opportunity lies in fostering attachment not just to the IP, but to the companies bringing them to life. A good precedent can be found outside the publishing world in A24, the disruptive film distributor turned cultural conglomerate. A24 was founded on the premise that digital-first marketing could be used to promote movies and create engagement in novel ways and at a lower cost than the industry's standards. Merch would soon turn central to this strategy, with limited-edition drops and hip collabs consistently sparking cultural commentary around the company's releases. Over time, A24's logo became "a seal of quality for smart, challenging, fresh US cinema"; its name, "synonymous with aspirational indie cool." Today, to buy any piece of A24 merch is to buy into, and put on display, a certain idea of cinema. It's the same kind of halo effect that publishers should aim for.

Experiential storytelling

If there is one thing every rightsholder dreams of for their IP, it's this: a home. While merch represents a valuable entry point into fans' lives, immersion remains the Holy Grail of worldbuilding. As Matthew Ball observed a few years ago about Disney's theme park advantage:

There is nothing that can compare to the impact of a child being hugged by her heroes. The ability to enjoy your favorite IP as “you” is unique and lasts a lifetime. [... ] Fans simply cannot enjoy DC or Lord of the Rings or Dragon Ball the way they do Disney’s Princesses, Pixar, most recently, Star Wars, and soon, the Avengers franchises. This fundamentally limits a franchise’s ability to grow love — the lifeblood (and profit driver) of all IP-based companies.

The entertainment world has woken up to that fact in recent years. In 2023, Nintendo opened not one but two Super Mario World parks in partnership with Universal Studios. This year, Netflix announced "Netflix House," "a year-round home for fans to live the stories they love," and Japan's Toei Animation partnered with Saudi Arabia's Qiddiya Investment Company to build the world's first Dragon Ball theme park in Riyadh. Even freaking Peppa Pig now has several parks to its name.

Meanwhile, book publishers have no such place to call their own. Today, readers gather in one of two ways: in small groups at local, community-forward bookshops, or in mass at large-scale events. Romance is a case in point. For years, the genre found fertile ground at fan conventions like Comic-Con, known for drawing in primarily comics, TV, and movie enthusiasts. Now, its growing cultural acceptability is attracting large enough crowds, and enough capital, that romance-specific conventions have emerged. There's Kansas City's GenreCon, Anaheim’s Steamy Bitcoin, Salt Lake City's Bookery Con, Atlanta's LOVE Y'ALL, or the mouthful that is the Romance Slam Jam Virtual Romance Book Convention. Like their non-book precursors, these events offer everything from signings and photo-ops to cosplay and memorabilia, providing publishers with numerous opportunities to engage readers. Still, even the most visited booth at a convention is only rented space. Without a stable home to invite fans in, publishers are missing a key piece of the engagement puzzle.

Some have tried to fill that void. Around 2016, a number of indie presses across the U.S. started to open their own stores. This had several benefits. First, it enabled publishers to get closer to readers' tastes and to influence them through curation, a chance to elevate the more niche genres and authors in their catalogs. Second, it was an opportunity to showcase the full extent of the creative journey, rather than just its output. Minneapolis-based Milkweed Editions foresaw "rotating exhibits related to the publishing process, such as cover designs and manuscript pages to offer insights into what they do as a publisher."

Now a few years in, book-and-mortar has maintained its appeal, though new attempts remain few and far between. Penguin opened its own bookshop in May 2022 in the lobby of its head office in Toronto. Drawing heavily from the publisher's graphic identity, the store showcases an abundance of branded merch including mugs, tote bags, and pencil cases, all neatly placed in paperback-shaped display cases. In June this year, Kazakhstan-based Foliant Books announced it is "launching its own bookstores, book fairs, and exhibitions to connect directly with its customers" across the country. I expect we'll see more publishers move in this direction.

This will come with challenges. Because retail lives and dies by foot traffic, not all publishers start out with equal chances. Penguin, for example, is self-sufficient: its size and longevity mean its catalog is substantial and attractive enough to warrant its own physical space. The company is also one of the few to have invested in its brand, with some memorable advertising campaigns and entire departments dedicated to partnerships and licensing. Tellingly, Retail and Experiential are two of the seven domains of expertise featured on the company’s website. All this has made it a household name uniquely equipped to make this kind of initiative work.

Things look very different for the rest of the industry. At the end of the day, a niche publishing house with a track record of only a dozen books and an audience still in the making isn't going to bring enough foot traffic for a standalone, permanent showroom to make sense. Unless they double as other kinds of businesses — think cafés or community spaces — to offset the seasonality of book sales, or join forces with similarly sized and ambitious competitors — something that, in an attention economy, many may feel wary of —, smaller presses will struggle to make the math work for them.

Fortunately, owning and operating an evergreen space isn't the only option. In the film & TV world, IP owners routinely use short bursts of real-world marketing to grow awareness and affinity around their projects. Netflix's activations, for example, have spanned limited-edition products (e.g., the McDonald's x Emily in Paris baguette), pop-up installations (e.g., the life-size Squid Game doll in Sydney Harbor) and full-fledged immersive experiences (e.g. the traveling Stranger Things Experience). By enabling fans to step into the worlds of their favorite shows and movies, activations like these heighten engagement, drive conversation, extend a property's shelf life, and provide valuable opportunities to gather data on fan preferences that can inform future marketing strategies and even content creation decisions. There's a lot here that publishers could learn from as they try to expand on their own IP.

But there's one particular area that I'd like to see them explore: contents tourism.

Whether or not you're familiar with the term, you probably know what it means — in fact, you may even have practiced it yourself. In media studies parlance, contents tourism (a literal translation from the “kontensu tsurizumu” theorized in the “Cool Japan” strategy) is a form of tourism whereby creative works such as film & TV, comics, video games, and novels are the primary motivation for visiting a destination. From writers' homes to set locations to theme parks, contents tourism is a global business.

Today, the concept is associated mostly with photography or film. Think, for example, of how many people visit Abbey Road to, literally, follow in the Beatles' footsteps, or walk around Montmartre reminiscing about Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Amélie. Cultural references such as these enrich visitors' experience of a place, imbuing it with meaning; they turn tourism into a personal and collective pilgrimage. And while older cultural works continue to move crowds, new ones are constantly entering the canon. Earlier this year, France's national cinema body found that "four out of five foreign tourists to Paris got an urge to visit after seeing a movie or TV series filmed in the City of Light." Two of Netflix's shows, Emily in Paris and Lupin, were direct contributors.

Meanwhile, you rarely hear about people traveling because they've read about a place in a book. For all the success of the Harry Potter franchise, it wasn't until the movies came out that King's Cross Station installed its photo-op replica of Platform 9 3⁄4. Unlike visual media, reading doesn't provide ready-made references; there are no scenes to replicate, no tableaux to reenact. However detailed a description, every reader needs to come up with their own representation of a place. Less recognizable in the wild, and therefore less shareable, literary references seem to have less of a pull as destinations.

It's a challenge worth tackling. For publishers, contents tourism is an opportunity to transpose their stories into the real world and to turn the introspective act of reading into a more social and extensive experience. To do that, the first step is to go back to the source material. Does a novel mention famous monuments? Maybe the author took inspiration from their own city and made the protagonist a regular at a real-world spot? Every one of these names is a cue to build off.

Once they have been identified, it's time to bring them to life. Maybe that's partnering with the protagonist's favorite café on a themed cocktail. Or designing a treasure hunt around a city, with its own "I was there" certificate and exclusive merch for sale at the end. (Japan, for example, is famous for its “stamp rallies” that encourage tourists to visit cultural landmarks.) Or having a photographer and props on site to make sure fans leave with memorable pics. Whatever the approach, the goal should be to add another dimension to an IP and to enable fans to forge a stronger connection with it through active participation.

The good thing is, the operational and financial lift doesn't have to be heavy. I'm not suggesting every book publisher launch an in-house travel agency here. It's about creating new touch points and fostering a sense of belonging through shared rituals. Publishers don't have to do it alone, either. Anime tourism, for example, has seen IP owners partner with localities and the fans themselves to come up with mutually beneficial cultural partnerships. So long as the resulting crowds remain manageable, local businesses and governments are likely to be publishers' biggest supporters in these endeavors.

Mastering eventization

For publishers, luxury editions, merch, and live experiences are all accretive opportunities. They’re about exploring new — or, in the case of luxury editions, so old as to be overlooked — paths for engagement and revenue. But expansion isn’t the only way to go: there are quick(er) wins to reap in reassessing the way things are currently done across the industry. The book release is one such process worth challenging.

The problem with “one-and-done” book launches

At the individual level, releasing a book is largely a one-and-done deal. A publisher will promote a book ahead of its release, and potentially double down for a short while if early sales show promise. After that, it will simply move on to marketing the next upcoming title on its roster. With limited shelf space for ever more contenders, physical bookshops ultimately send back unsold inventory, depriving so-so performers of potential long-tail revenue.

Breaking through is therefore imperative. No amount of ebook sales will compensate for a lackluster physical debut, and adaptation offers rarely come knocking at the door of unsuccessful IP. Save for a raving fan randomly bringing it back from oblivion, a book that didn't make it on its first try has zero chances to resurface. In France, over the 2021-2022 period, a whopping 13% of all books produced ended up being returned by retailers to be destroyed

By contrast, other cultural goods enjoy much greater economic longevity. In Hollywood's traditional windowing system, for instance, a feature film goes (in an optimal scenario) through a theatrical window, enters VOD and physical retail, then premium TV networks, then free TV — today, a video streaming platform might also just swoop in the rights at any point along this journey. Together, these distribution channels and revenue streams — some successive, others overlapping — make up a fairly diversified lifecycle.

Granted, all movies do not benefit equally. For example, theatrical releases typically determine how revenue from subsequent windows is negotiated; movies that underperform on the big screen or skip it entirely remain handicapped throughout the rest of their lifecycle. But multiphase distribution and monetization mean that laggers at least have a chance to catch up.

Because they lack such optionality, book publishers should be doing everything in their power to make the most of what little time they get in the public eye. A book needs to enter the marketplace with a bang, lest it go forever unnoticed.

Timing as a differentiation strategy

Like the film industry with its summer blockbusters, horror-heavy October, and animated movies around Christmas, the publishing industry is highly seasonal. Summer vacations, the holiday season, and New Year's resolutions are some of the cultural landmarks that publishers have learned to build around in order to sync up with consumers' wants, needs, and means.

This cyclicity is both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, publishers can rely on clearly identified periods when they know consumers have leisure time, willingness to pay, or both. For example, self-help does well in Q1, novels in the summer, and children's books ahead of the holiday season. No need to guess, then: depending on what sort of book you're selling, your ideal release date is almost predetermined for you. On the other hand, defaulting to tried-and-true windows can deter publishers from thinking creatively about their editorial calendars. But what if savvy timing could be a differentiator in and of itself?

Publishing's Two Approaches To Timing

For publishers, timing usually serves one of two goals. The first one is about standing out. Indeed, why would you release a book at the same time as everyone else if you can avoid it? All things being equal, hitting the shelves at a less crowded time should allow you to capture more mindshare and be featured more prominently both on- and off-line. The same is true when it comes to avoiding the competition of a particular author, as repeat bestsellers have a way of sucking the air out of the room for everyone else.

The second, perhaps counter-intuitive, approach is about blending in. On this end of the spectrum, the goal is to tap into a general momentum by featuring alongside others at a specific time. It's a bet that a rising tide lifts all books, if you will.

In France, this is exemplified by the "rentrée littéraire," a period running roughly from the end of August to the beginning of November that sees large numbers of new books hit the shelves. For publishers, the benefits are twofold. At the industry level, the rentrée littéraire has become this highly anticipated cultural landmark for readers and professionals alike. It serves as a free collective marketing campaign, with abundant media coverage spanning reviews, interviews, and listicles. At the company level, publishers use the event as a way to garner attention ahead of the holiday season, and to have their books considered for some of France's most prestigious literary prizes, several of which are handed out around the end of the year. Critical and commercial success are inseparable here: the laureate of the Prix Goncourt, France's premier prize, will typically see its sales multiplied overnight by a factor of between 3 and... 33.

Inevitably, the rentrée littéraire also brings about brutal competition. In 2023, 466 books were released over that timeframe, more than market demand could possibly absorb even with all the marketing in the world. (This tally was actually down from a peak of over 700 in 2010.) For publishers, it's a catch-22: either enter the fray at the busiest time of the year to have a shot at winning a prize, or hope to stand out in some way during no-prize season. Call it overconfidence or basic risk/reward math, many in the industry continue to play the rentrée's game.

What book publishers can learn from Barbenheimer

Somewhere in between these two approaches is a potential third one: a middle way that would leverage synergistic excitement yet still allow for differentiation between participants. What could it look like?

Again, the movie industry offers some pointers. It’s no secret that with limited time, attention, and discretionary spending, consumers will only go to the theater to see so many movies. One way producers and distributors typically hedge their bets is by making sure that their movies are not debuting at the same time as similar or overpowered products. For example, any Marvel or Fast & Furious opus will usually come with enough marketing to drown out its rivals; as a general rule, going head to head with these franchises is a sure way to underperform at the box office. Last year, Oppenheimer producer Charles Roven tried to have Barbie's release date changed so that the two movies wouldn't open on the same day.

Yet the success of "Barbenheimer" was proof that things don't have to be quite so zero-sum. Encouraged by ubiquitous marketing activations, fans were quick to seize the event's memetic potential and turn it into a cultural phenomenon. This, in turn, incentivized theater owners to program double features that allowed movie-goers to join in on the fun, with costumes and hats galore — UK cinema chain Vue reported that 19% of people who booked tickets to see Oppenheimer also bought tickets for Barbie. At the end of the day, both movies, and the studios behind them, benefitted commercially from what first seemed like a winner-take-all situation.

Publishing is, arguably, a more conservative industry than Hollywood. But this doesn't mean that publishers can't learn from other corners of entertainment. The more time they spend on BookTok, the more authors and publishers are having to up their own video storytelling game. Meanwhile, as I mentioned earlier about romance, cultural practices — from book signings to cosplaying to contents tourism — have grown increasingly similar across media. Fans go to similar events, engage in similar activities, and create and consume content that brings together their various interests. (On Goodreads, "Romances set in nerdy spaces" are their own sub-genre.) Events like the Harry Potter-based, Warner Bros.-managed “Back to Hogwarts Day” are proof that book fans will embrace the exact same codes as their music and movie peers, when given the chance.

What tangible tactics might publishers draw from the Barbenheimer craze as they lean into eventization? Can they, formally or not, pair up with a competitor to generate anticipation for a theme or genre in which they have a vested interest? Can they (playfully) engineer beef to attract attention? Can they sell crossover merch, and co-meme their way to success?

Now, I'm not suggesting that every publisher do all of these things at once; considering the industry's current marketing practices, that would be overkill for most. Still, there's a lot of wriggle room between doing nothing and going all-in. Publishers should view these tactics as add-ons that they can integrate into their typical promotional campaigns to boost anticipation and engagement. Although these components are likely to perform best together, the goal for now should remain experimentation.

One potential pushback I'm expecting here is that these strategies need existing fandoms to work. I simply don't think that is true. Were all those who rushed to see Barbie and Oppenheimer actual fans of Barbie (the fashion doll) and Oppenheimer (the tormented scientist)? Did they expect to someday be cosplaying as the father of the atomic bomb? Probably not, but that didn't prevent them from joining in on the fun! This should come as reassuring news for those publishers who might feel like their own IP doesn't have what it takes to elicit excitement just yet. Eventization is a way to manufacture that excitement, to go from hype to fandom rather than the other way around.

Bringing Back the Serial

Remember the challenge I outlined earlier: "entering the marketplace with a bang" was only one part of it. Next, a book has to actively sustain attention — ideally both reader interest and media coverage, one often leading to the other. The problem is, the current one-and-done model appears antithetical to those goals.

Here, again, other areas of entertainment offer a sense of what could be. Since the advent of streaming, much ink has been spilled about the respective benefits of the "binge" and episodic release cadences for TV shows. On the one hand, a customer-friendly model that creates a sense of urgency and encourages memeability due to the immediate availability of the source material. On the other, a battle-tested model that leaves room for anticipation, conversation, and conjecture to form around so-called "appointment entertainment." To this day, various streaming platforms continue to experiment with both schedules, sometimes even combining them to make sure they can serve all viewing preferences with a fresh stream of content at any given time.

Serialization exists in books, too. In fact, many of today’s most commercially successful properties — from Harry Potter to Fifty Shades — were conceived as series from day one. As with TV and film, book series enjoy compounding benefits as brand awareness builds up with each new installment, streamlining promotion for subsequent releases. And as with TV and film, fan discourse will usually fill the void in between two volumes, a credible sign that a franchise has struck a chord with readers.

But we're still only comparing apples to oranges here. The discrepancy becomes clear if we phrase the problem as an analogy: if the book is to the book series as the season is to the TV series, then what is the book equivalent of the episode?

The obvious answer to that question would be, the chapter. The difference is, book publishers do not release chapters individually, the way TV networks and streaming platforms can with episodes. Put differently, the book lacks a smaller atomic unit that publishers could split it into for creative, promotional, and monetization purposes. In TV parlance, it's stuck with the binge model.

A Short History of Serialization

Things weren’t always that way. Centuries ago, when books were premium goods unavailable to most, publishers would often publish large works in lower-cost fascicles, some of them only a few pages long. This allowed them to expand the market for the written word and gauge the popularity of a particular work without incurring the expense of bound volumes.

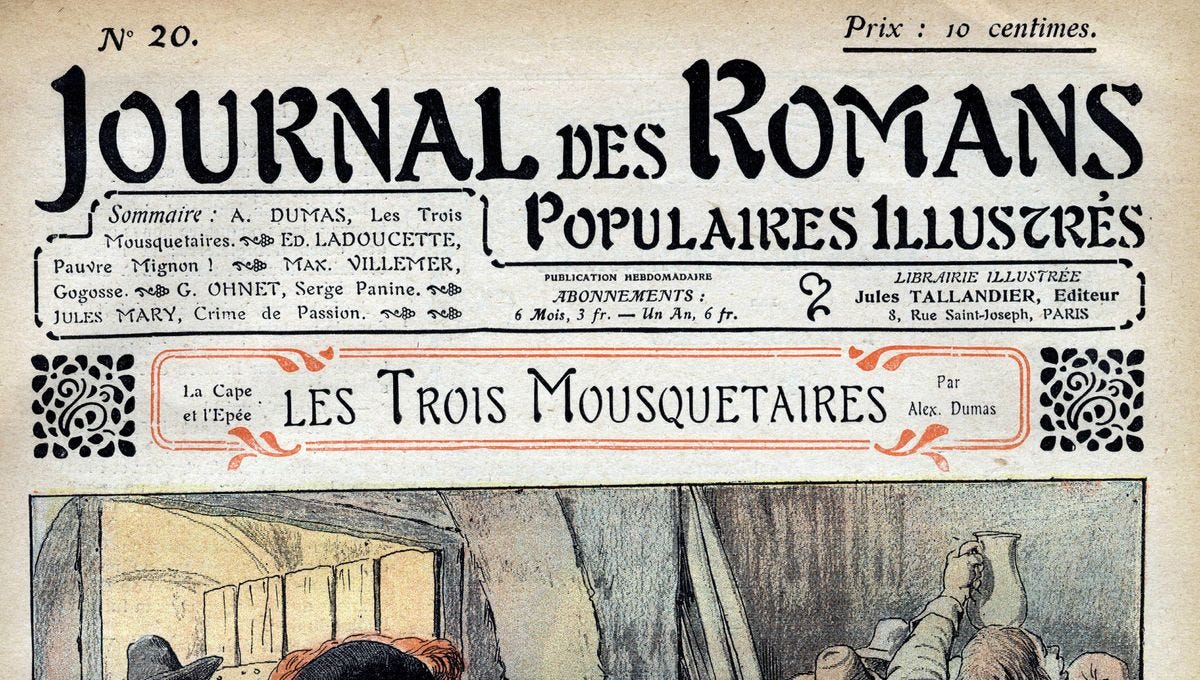

With the advent of modern newspapers in 19th century Europe, serialization changed. Around 1830 in France, more and more papers started using the “feuilleton” — the lower part of the front page, usually dedicated to cultural and educational commentary — to showcase short works of fiction. It was an instant success. In the following years, publishers started commissioning longer and longer works to keep readers coming back. Novels replaced novellas; the “roman-feuilleton” was born.

At first, newspapers only published finished works, with serialization being used to introduce a novel to the public for cheap and pave the way for future publication in volumes. With their large reader base and often vocal political stances, periodicals garnered far more attention than authors could hope to attract on their own. This meant a larger surface area for public scrutiny and moral censorship, which often boosted authors’ book sales further down the line.

It wasn’t long before serialization transformed again. In 1836 France, the introduction of ads alongside the news enabled two papers, La Presse and Le Siècle, to subsidize their publications and massively undercut their competitors, forcing them to follow suit. Incentives changed overnight. To keep readers engaged and advertisers happy, newspapers now needed a steady flow of new literature. Novels got even longer so they could be stretched over even more installments: Dumas’ Le Comte de Monte-Cristo ran for almost two years, and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina for four years. The content evolved too, incorporating more riveting adventures and new narrative devices like cliffhangers and recurring characters, and sometimes even responding to the public’s reaction from one issue to the next.

Business was good while it lasted. By 1840, serialization through newspapers was the preferred way of consuming novels, and was supporting hundreds of writers. Beside the aforementioned Dumas and Tolstoy, Balzac, Flaubert, and Zola, but also James, Doyle, and Dostoyevski all had their work published under this model. By 1875, the continued progress of literacy among the population and the generalization of advertising had led to an explosion in readership, with circulation reaching 5.5 million readers in Paris alone. But harder was the fall. Together, growing competition from other forms of entertainment, the impact of the two world wars on the newspapers trade, and the commoditization of books put an end to the serial’s century of dominance.

Lessons From the Past

Today, serialization has been largely abandoned. With their synergistic delivery method gone, the French roman-feuilleton and its international equivalents remain only as memories, the perfect solution to a problem that no longer exists. They have served their purpose.

Yet the principles they surfaced still stand true. Now as ever, serialization fosters loyalty and creates anticipation, which fuels, and then feeds off, cultural discourse — any TV show that dares to pace itself rather than cave to the binge model can attest to it. That it took off in a different time and a very different media ecosystem doesn’t change that fact. The salons may have been replaced by the infamous watercooler conversation, the “word on the street” by the internet, but serialization remains the surest way to achieve cultural synchronicity.

For publishers, it’s a path worth exploring again. Not out of nostalgia for the golden age of newspapers, but because the format applies just as well, if not better, to the distribution channel du jour. For books, more, shorter installments mean not just a more tangible presence on people's bookshelves, but more opportunities for awareness and connection, through release announcements, interviews, and book signings. With each new release, a chance to reignite the media engine. If publishers are serious about growing their brands, this strategy could hold promise.

Of course, it won’t be for everyone. For serialization to make sense, a few conditions need to be met.

First, a book needs to be long enough to even call for serialization, lest readers view it only as a publisher's attempt to milk their wallets across multiple tomes. Second, serialization also needs to make sense narratively. Without salient cliffhangers, even a thick book might be better off published as a single volume rather than forced into multiple installments. That being said, if a compelling business case can be made, I expect that authors would quickly cater their writing to the format’s constraints, the same way their 19th century predecessors did.

From an operational standpoint too, serialization poses challenges. Back when serials were released in periodicals, production was just-in-time and publication could be stopped as soon as interest started to wane, without publishers incurring sunk costs. Sure, readers would be left hanging, but with writers basically fighting to get into the system, there was enough to go around that papers could just switch to another serial.

With books as the de facto delivery mechanism, serialization is a very different matter. Today, the entire industry is set up around a final, standalone product. Book rights are purchased upfront based on sales forecasts, not gradually based on unpredictable word count. Because publishing and printing have been unbundled, publishers can’t haphazardly print installments themselves anymore. Printers demand predictable timelines and volumes and can’t accommodate the kind of variability that comes with serialization. As for distribution, the combination of overwhelming supply and limited real estate has made physical bookstores painstakingly picky about which titles they carry. For them, serialization means tedious inventory management and logistics. Simply put, bringing back serialization would require reengineering a large part of the value chain.

Fortunately, several catalysts are converging that make now possibly the best time to experiment.

Culturally, readers’ growing enthusiasm around craft — displayed on BookTok and fueled by it — is an opportunity for publishers to rethink what a book can be. While cover art and premium materials are obvious options, the window of opportunity may be closing soon as more in the industry level up their design acumen. Serialization offers another compelling, and, for now, a more differentiating route.

There is clear appetite for the format. In the digital realm, Wattpad — a company I’ve covered in depth in the past — has leveraged serialized fiction into an entertainment giant. As of July last year, the company claimed 97 million Monthly Active Users who collectively spend more than 26 billion minutes a month on its platform, with an average engagement time of 60 minutes (!) per user and per day. The brevity of the writing takes nothing away from its cultural impact: in 2021, research showed that Wattpad clocked more mentions on TikTok than Audible, Kindle, and Goodreads combined.

Serialization applies to non-fiction, too. Cultural critic Ted Gioia leveraged his large subscriber base on Substack to publish his book Music To Raise The Dead. Meanwhile, a dedicated platform can be found in Books in Progress, an online “public drafting tool” where authors can make their drafts available for comment from the public. The platform was developed by Works in Progress in partnership with Stripe Press and multi-author Steward Brand. It is currently being used to publish Brand's upcoming book, Maintenance, with Brand publishing and opening up individual sections as he writes them.

Logistically and economically too, the industry has reached a point where smaller, more deliberate batches are starting to make sense. Cent Mille Milliards, a French indie publisher, prints books only on demand. This means zero stock, zero returns, and evergreen availability, an all-out anomaly compared to industry standards. When combined with business models like preorders and subscriptions that afford greater financial predictability, this sort of infrastructure could help publishers and even self-published authors make serialization a viable strategy.

Bringing Fun Back to Publishing

The publishing industry's reliance on BookTok may be a ticking time bomb, but the strategies I've outlined here represent a playbook for publishers to regain control of their destinies. By embracing deluxe editions, merch, experiential storytelling, eventization, and serialization, they can build stronger, more resilient brands that engage readers beyond the confines of any single platform.

These approaches aren't just about monetization — they're about fostering genuine attachment and a sense of belonging. In an age where readers crave analog experiences, publishers have a unique opportunity to position themselves as tastemakers, impresarios, and worldbuilders rather than mere vendors of commoditized content. The path forward may not be easy, but the rewards could be transformative.

Ultimately, the future of publishing lies not in chasing the latest social media trends, but in bringing to life and enhancing the wonders of the written word. By making books into objects of desire, events to be anticipated, and worlds to be explored, publishers can bring the fun back to their industry — and ensure their own survival in the process.

That’s it for Part III! In Part IV, I’ll dive deep into Monsieur Toussaint Louverture, a French publisher whose opinionated curation and attention to detail represent the best of what indie publishing can be.

Thank you for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this essay, please consider giving it a like and take a minute to share it with others. It really helps.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts! You can find me on X, or just reply to this email.

Thanks to Jimmy for reviewing a draft of this piece.

Thanks for sharing this piece, full of interesting stuff as usual 👍