A Playbook for Playful Publishing, Part IV

Monsieur Toussaint Louverture, or Publishing as Craft

Hi there! I’m Maxime, and you’re reading Recreations, a newsletter about the intersection of media, technology, and culture.

You’re receiving this either because you subscribed or because someone forwarded it to you. If you’re in the latter camp, you can subscribe here or via the button below.

Welcome back to another installment of A Playbook for Playful Publishing.

In Part I: The Promises and Trappings of BookTok, I unpacked BookTok’s workings, why the platform might have looked so appealing to publishers when it emerged, and why its ever-growing influence actually threatens the industry’s long-term prospects.

In Part II: On Judging Books (and Publishers) by Their Covers, we explored exactly why we care about a book’s cover so much, what messages it sends and to what purpose, and why its pull has never been stronger.

In Part III: The Playbook, I laid out five interconnected strategies that publishers can explore to generate engagement and revenue and to grow awareness beyond individual IPs and toward their own brands.

This here is Part IV: Monsieur Toussaint Louverture: Publishing as Craft, a deep dive into the work of Monsieur Toussaint Louverture, a small French publisher whose playfulness and attention to detail represent the best of what indie publishing can be.

Enter Monsieur Toussaint Louverture

Monsieur Toussaint Louverture is a French indie publisher of fiction based in Cenon, near Bordeaux.

It was launched in 2004 as a literary review focused on contemporary fiction by Dominique Bordes and Julien Campredon. At the time, Campredon was a seller for French daily newspaper Le Monde and had been dabbling with novella writing. Bordes was no stranger to books either, having worked successively as a layout artist, an editorial assistant, and a book seller. What he truly wanted, however, was to become a publisher; the journal was, in his own words, his "Trojan horse.”

Today, the company publishes seven to ten books a year. You’ll hardly find more indie than that. For comparison, as of 2022 Hachette Book Group (HBG) published "around 2,100 books a year in the adult segment as well as 500 children's and YA books and 750 audio book titles." Hachette Livre, HBG's parent company, publishes an average of 15,000 books per year.

Size would be enough to make many self-conscious. But Bordes, who has been steering the ship alone since Campredon’s departure in 2012, wears his difference with pride. In interviews, he likes to describe his boutique as “in the margins”, and himself as an outsider. Geographically, first — located in the South-West of France, and with a population of 25,000, Cenon is certainly far removed from the overwhelmingly Parisian milieu that is the French publishing industry. Symbolically, second — Bordes says he’ll always feel a natural kinship toward marginal literature.

Marginal or not, the company’ quest for singularity has materialized in two main ways: bold editorial choices, and beautifully crafted books.

Experimentation as a Rule

At first glance, trying to pinpoint Monsieur Toussaint Louverture can feel misguided. In an industry so dependent on marketable labels, the company seems to refuse simplification. In a marketing blurb from 2012, the company alluded to three main threads: "the forgotten, the unknown, and the unusual." Today, we're told it publishes books "regardless of their themes or genre, focusing only on their respective quality, power, and richness."

The vagueness of this scope may come as a surprise. Unlike the giants that dominate the industry with their all-encompassing catalogs, most indie presses opt to specialize in one genre or another from day one. By niching down, they avoid competing for the same rights as their deep-pocketed peers, and make their offerings easier to market to readers — as I wrote earlier, “The more specific the editorial stance, the easier it should be to come up with a unique aesthetic that reflects it.” Eclecticism, on the other hand, seems to afford optionality only at the cost of editorial and commercial clarity. That Monsieur Toussaint Louverture would take that path nonetheless is worth unpacking.

The decision can, in large part, be traced back to the company’s origins. In its first few years, the company-to-be already displayed what would remain one of its most defining traits: a love of experimentation. Monsieur Toussaint Louverture’s first book, a collection of novellas titled Brûlons tous ces punks pour l’amour des elfes, conveniently came from Campredon. First-time contemporary fiction, a continuation of the company’s beginnings as a journal, lived alongside a few oddities, including the Livre du Chevalier Zifar, an adventure tale written in 14th century Spain.

The first commercial win came in 2011 after years of labor with a new translation of Frederic Excley's A Fan's Notes, which sold 40,000 copies. Success prompted the company to double down, rejuvenating one overlooked American or European author after the other with ambitious new takes. Translations have made upf almost the entirety of its output since at least 2014, a statistic that makes it akin to the small but mighty foreign literature specialists that have been raking in many of the most prestigious awards for the past few years.

This interest is no coincidence. In the English-speaking literary world, large publishers often reject non-English literature for being hard to market or for requiring translation work in the first place in order to reach global audiences. As a result, those willing to put in the work and translate a book on their own dime can often acquire interesting work for cheap. Meanwhile in France, “foreign literature” also includes… English. This means that publishers have at their disposal an enormous backlist of authors whose work they might be able to dust off and present in a new light with a little marketing magic. Monsieur Toussaint Louverture followed this script to the letter in 2017 when it repackaged Jack Black’s 1926 novel You Can’t Win — which was already available in France at the time — under not just a new translation but even a new title.

Last but not least came the graphic novels, another category where the company has earned critical and popular acclaim thanks to singular picks. The first volume of Moi ce que j’aime chez les monstres, a translation of Emil Ferris’s My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, earned it its second commercial success (160,000 copies sold to date) as well as a number of industry awards. Other titles, notably a luxury set of Lynd Ward’s six “wordless novels,” have been sold out for months.

A Certain Idea of Literature

How this portfolio came to be is more art than science. Bordes, who says he doesn't like to read in English, rarely reads a book before acquiring the rights for it. Instead, he will look at comments, Amazon reviews — anything that might give him a sense of what a book is about, and who it speaks to. He acquired the rights to Excley's A Fan's Notes on a whim after coming across the author's name serendipitously in the preface to another book.

This comes in stark contrast with the industry’s state of affairs. On the one hand, many of the largest publishers are unashamedly demand-driven — as I wrote in Part I of this series, “Wherever you look, BookTok — what the community wants, and how to deliver it — is now the single biggest motivation behind the industry’s every move.” On the other hand, indie presses are usually perceived (and sometimes, paint themselves) as governed by sheer taste and intuition, the last bastion willing to take risks to support bold literature irrespective of its commercial prospects. From this view, Bordes’s bottom-up research process certainly stands out.

For all its variety, the catalog also displays some striking commonalities. The first one, length, is hard to miss. Ken Kesey's Sometimes a Great Notion is 896-page long; David James Duncan's The Brothers K, 832-page long; Mariam Petrosyan's Дом, в котором... (La Maison dans laquelle in French), 1088-page long. Even its graphic novel picks are on the longer side. Such expansiveness, too, can be explained by Bordes's influence — he has said that big books are "in [his] DNA." At a time when people's attention spans are supposedly getting shorter every year, supporting longer works is notable in and of itself. It's a sign that Monsieur Toussaint Louverture stands for a certain idea of literature, one where both authors and readers give stories the time and space they need to unfold.

But these books have more in common than just their size. Browse through enough of them, and you begin to notice similarities in theme, tone, or form. Misfits and outcasts (J. Robert Lennon's Mailman or Steve Tesich's Karoo). Coming-of-age tales (David James Duncan's The River Why or Russell Hoban's Riddley Walker). Singular prose (Riddley Walker), typography (Mark Z. Danielewski's House of Leaves), and creative workflows (My Favorite Thing Is Monsters). Whether narrative or formal, the same sense of rebellious freedom, something decidedly punk, seems to run from one book to the next. Bordes’s own marginality, in editorial form.

Publishing as Craft

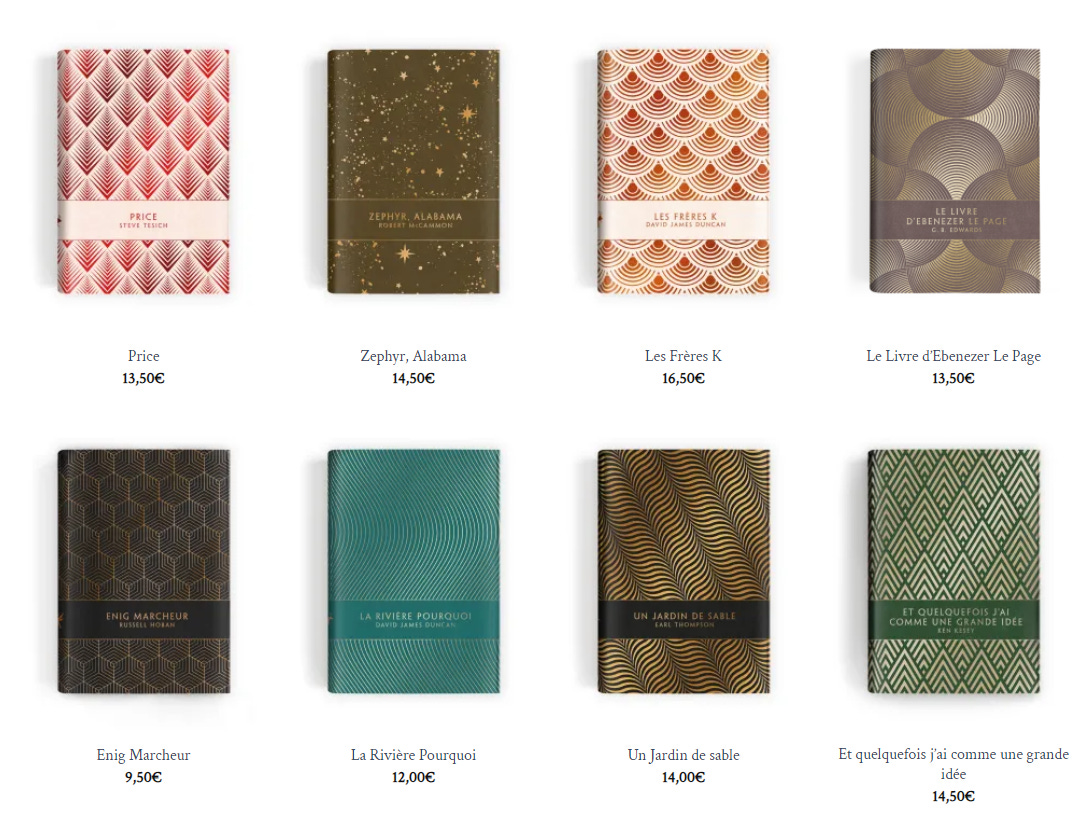

While there is much to say about the company’s curatorial track record, equally significant is its interest in books as objects. On its website, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture proudly presents itself as "a publishing house driven by a passion for literature and an attention to details" and advocates for "a return to the pleasure of beautiful books." Of its collection "Les grands animaux", the company cheekily says it wants the books "beautiful enough that you'll want to steal them, but accessible enough that you won't have to."

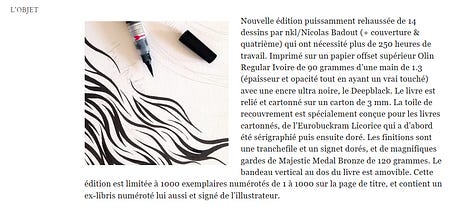

These aspirations manifest in a number of ways, from the commission of original illustrations — a line of spending most indie publishers tend to avoid — to the quality of the materials used and the variety of the techniques involved. Dabbling with graphic novels, in particular, meant Monsieur Toussaint Louverture had to hone the sort of skills that may evade less eclectic publishers. For Lynd Ward's "wordless novels," the process combined a specific type of ink (for "deeper, softer blacks"), tinted paper (to soften the contrast with the artworks), and a recto-only layout to honor the artist's original intent and allow for a better reading experience.

Maintaining such high standards is not just a source of pride, it's also a unique selling point. Accordingly, the company seizes every opportunity to showcase its craft and give readers a glimpse into the printing process. The profile page for the Wakonda edition of Kelsey’s Sometimes a Great Notion features a whole section packed with the books’ specs and technical printing terms. Meanwhile, on Facebook and Instagram, virtually every post contains glamourous close-ups of one or several books in various stages of development — some in staged photoshoots, others, literally, hot off the press. In the comments, readers old and new can be found raving about the artifacts, sharing pictures of their growing collections, and impatiently awaiting new releases. If testimonials are to be trusted, it’s not uncommon to see readers switch from ebook to paperback midway because they liked the physical version so much.

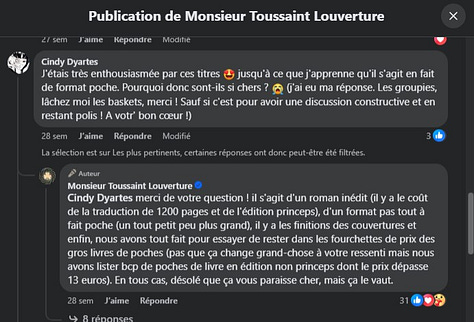

On paper, such craftsmanship has only upside: it catches people's eyes both off- and online, travels farther on social media, and offers valuable supporting material for marketing through behind-the-scenes content. But it also comes at a price, one that not every reader might want to pay. To someone who complained on Facebook about the price of a particular pocket-sized book, the team obligingly listed the many factors that had contributed to it. Still, it’s hard to explain away someone’s price sensitivity. Though anecdotal, this instance evidenced the paradox of premium: craftsmanship simultaneously expands a book's "Total Addressable Readership" by appealing to book collectors as well as to actual readers, and limits it by possibly deterring the more budget-minded buyers.

At the end of the day, craftsmanship is a stance and a matter of positioning — nothing to feel sorry about. As hard as Monsieur Toussaint Louverture may try to reconcile desirability with affordability, there is only so much expenses it can squeeze. Today, its website can feature as many as three different editions of the same book, each at a different price point, and it’s the most luxurious ones, admittedly the most limited series, that tend to run out. It might as well lean into it.

But however nice the books may look on the outside, the most striking insight into the company’s vision lies inside them. At the end of each volume is a page that includes specifics such as the name, type, and density of the paper, the name of the font or fonts used, and even the dimensions of the book. Though this sort of minutiae might feel gratuitous, they're presented in a way that makes them an integral part of the work itself, wrapped up in the story and its lore. For Mariam Petrosyan's La Maison dans laquelle, whose story takes place in a larger-than-life orphanage, the publisher points out that, regardless of the book's actual dimensions, "the world it contains is limitless." For Russel Hoban's post-apocalyptic novel Riddley Walker (Enig Marcheur in French), we're told the paper was "collected from here and there amidst the ruins of the ancient world." The list goes on. One lyrical endnote at a time, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture is proving that even a book’s technical specs have creative value. In the publisher’s eyes, craftsmanship is an extension of literature, and no detail is too small.

Unpacking Blackwater

Having just reached the noble age of 20, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture has plenty of interesting books to show for it. Here, however, I’d like to highlight one in particular: Blackwater.

Blackwater is a Southern Gothic family saga by Michael McDowell, an American novelist and screenwriter known primarily for his work on Beetlejuice and The Nightmare Before Christmas. It covers several generations of the influential Caskey clan as they make their fortune in the fictional town of Perdido, Alabama during the first half of the 20th century. The series weaves together historical events like the Great Depression and the Second World War, themes of symbolic and physical violence, and a supernatural undertone inspired by folk culture.

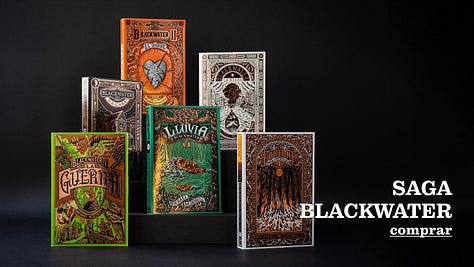

Blackwater was first released in the U.S. as a monthly serial by Avon Publications (now part of HarperCollins) between January and June 1983. Today, U.S. rights are managed by Valancourt Books, which last published it in a single volume in 2017. For its part, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture published it in six biweekly volumes between April and June 2022.

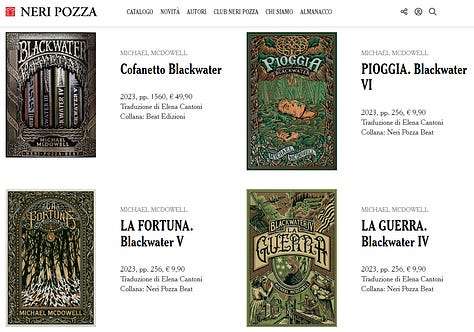

It was a breakout success, selling 35,000 copies by May 2022, 120,000 by June, 300,000 by August, 500,000 by November, 800,000 by May 2023, and a million copies by April 2024. These numbers understandably piqued interest from elsewhere in Europe, with indies Neri Pozza and Blackie Books respectively snagging the rights for Italy and Spain, and Doubleday (a Penguin subsidiary) recently acquiring the rights for the UK. By August 2024, over 1,150,000 copies had been sold in France alone, along with 300,000 in Italy and 300,000 in Spain.

There are three reasons why Blackwater makes for a great case study.

First, Dominique Bordes himself has declared that the series epitomizes his approach to publishing; it's worth understanding why.

Second, Blackwater’s huge commercial success has generated more visibility — more reviews, more interviews, more social posts — than what Monsieur Toussaint Louverture had historically received, and thus, more research material for me to unpack. The fact that other publishers have now entered the fray has only reinforced that fact.

Thirdly, and crucially, Blackwater wasn't a one-off, but the beginning of what is now "La Bibliothèque Michael McDowell" (literally, The Michael McDowell Library), a collection that will see the release of five more of the author's books. Monsieur Toussaint Louverture released Les Aiguilles d'or (Gilded Needles) was published in October last year; Katie debuted in April, and Lune froide sur Babylon (Cold Moon Over Babylon) in October. Two more books are scheduled for release in 2025. Now, there’s every indication that Neri Pozza in Italy and Blackie Books in Spain have similar plans. Given such a packed calendar, I was especially interested in exploring how Blackwater is paving the way for the rest of the collection in terms of both brand guidelines and marketing practices.

Pushing Craft to the Max

It’s fair to say that Blackwater pushed Monsieur Toussaint Louverture's obsession with craft to the max.

As with every other book, the company set out to produce something differentiated and enticing — desirable — that would also honor the spirit of the original work. For Blackwater, Bordes envisioned the covers as playing cards, each book its own unique combination of colors and ornaments yet still part of a coherent set. With its Southern Gothic influences, rich historical backdrop, and multigenerational family intrigue, the series provided ample material for interpretation.

To make the most of it, Bordes turned to Pedro Oyarbide, a Spanish illustrator who had experience designing card decks. One year later, Oyarbide turned over the final identity for the series, a set of six illustrations with Art Deco-inspired adornments, insignia, and symbols referencing the story, places, and characters inside.

At that point, the work was only half finished. Along with the visuals, Bordes also wanted the books to have texture; they needed to not just look good but feel good, too. After the coloring, this required using a combination of relief printing techniques, namely foil stamping, whereby pre-dried inks are transferred to the surface of the paper at high temperatures, and embossing, which gives the paper stock dimensionality by pressing dies into it. Together, the two manifested a level of care rarely seen in books sold at that price range.

It’s hard to overstate how much conviction all these efforts must have taken. For starters, Bordes's decision to have entirely distinct illustrations for each volume, instead of, for example, mere variations in color, not only raised costs but also lengthened time to completion due to the inevitable back-and-forth with the creative. That Oyarbide was allotted an entire year to deliver his work is remarkable in itself.

Looking further along the production line, the book’s elaborate design meant the covers and pages had to be printed separately by two distinct companies, whose respective production timelines then had to be reconciled for the final product to be completed in time. With their foil-stamped details, the covers required a special kind of press and “at least 13 or 14 days” of patient iteration to make sure the output was as good as it should be.

For such logistics to make economical sense, a certain threshold thus needed to be met in terms of volume. Monsieur Toussaint Louverture aimed for a first run of 100,000 copies, with an estimated breaking point at 48,000 copies sold. Those were lofty goals to say the least. For context, roughly 66% of frontlist books from the top 10 publishers sold less than 1,000 copies over 52 weeks in the U.S., per Kristen McLean, lead industry analyst at NPD BookScan. Taking into account small presses and independently published titles, about 98% (!) of new books sold fewer than 5,000 copies in the “trade bookstore market” that NPD BookScan covers. The bar was especially high for a small publisher and a dead author most readers in France had never heard about.

As if that wasn’t enough, the team would also have to go through all the practicalities again — the special machinery, the manual revisions, the distinct production timelines — in the event that consumer demand would call for reprints. And, as mentioned, it wasn’t long before reprints were, indeed, very much needed. In short, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture was all-in.

Ultimately, all those efforts paid off. Mainstream media put the covers front and center at launch, calling them “gorgeous” and “hypnotizing.” As with previous releases, the sheer length and complexity of the design process became the publisher an opportunity to embark readers on a greater creative journey, with every new development teased on social media with tantalizing close-ups and descriptions. One month after the last volume of the series was released, a short behind-the-scene look at the process and those that had made it possible received praise, with many readers sharing that the cover was what had drawn them to the books in the first place. Yet another confirmation that craft was not a cost, but an investment.

Serious About Serialization

Looks were not the only aspect of publishing that Monsieur Toussaint Louverture ended up disrupting for Blackwater. Equally important was how the team single-handedly brought back the serialization model of old.

Initially, the plan was to publish the whole of Blackwater as a single volume — the “normal” way, and how it was last published by Valancourt in the U.S. That plan was scratched after Bordes learned about the book’s original monthly cadence. In the publisher’s own words, "Sticking to the author's intent felt like a no-brainer." (Interestingly, a more recent interview surfaced another story: in this version, it’s waiting for the translator to deliver one volume after the next that prompted Bordes to think of serialization as a creative device).

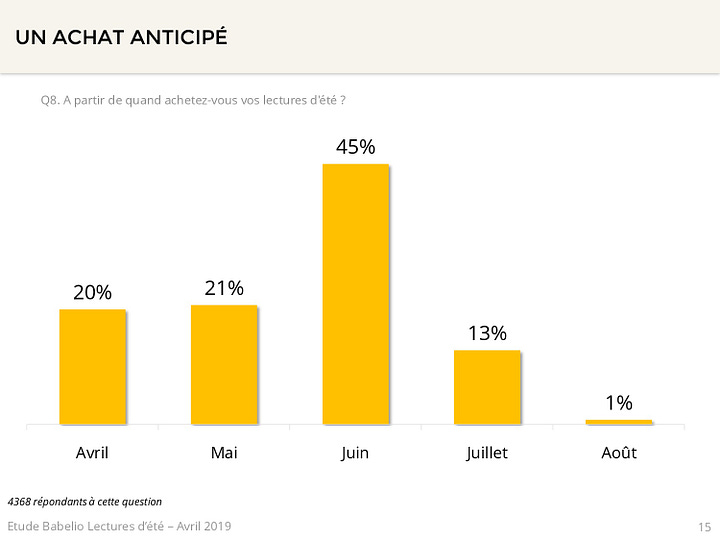

Once that choice was made, the matter of periodicity remained. Too little time between two installments, and readers would feel rushed. Too much, and Monsieur Toussaint Louverture would struggle to reengage them. In an era where book serialization was no longer part of people’s cultural habits, the team’s choice of a biweekly cadence instead of the saga’s original monthly one meant it would have an easier time keeping things fresh in readers’ minds. Perhaps secondarily, it also allowed it to make use of the industry’s notable seasonality, with the upcoming summer vacations giving new readers the opportunity and time to take on a saga they had heard of in the months prior.

Like the book’s design, serialization paused its own sets of challenges.

As I explained last week, serialization took off in the early 19th century as an engagement tool for the modern newspaper industry, at a time when circulation was booming thanks to rapid advancements in printing technology and literacy. With books now the default delivery mechanism for fiction, the model has lost most of its relevance and appeal: the industry — its value chain, its incentives — is simply no longer built to accommodate it.

For Monsieur Toussaint Louverture, going with six smaller tomes rather than with a single large one meant more steps in the printing process, possibly hindering economies of scale, as well as more complex logistics and warehousing, which likely meant higher distributor fees. Business-wise, there was also no guarantee that bookstores would stock the series as Monsieur Toussaint Louverture needed them to. Had the first tome underperformed, they would've had no incentive to promote the rest of the series in the following weeks.

In these circumstances, failure was not an option. Not only could the sunk costs of the French translation and the original illustrations only be amortized if the entire series did well, the printing process was likely already in motion in order to stick to the heavily marketed timeline of one tome every two weeks.

Riding the Wave of Success

After the runaway success of Blackwater, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture is no longer just a quirky indie press; it now has a proven bestseller under its belt, and a blueprint for how to capitalize on that momentum. It seems posed to leverage its growing brand recognition and fan engagement to drive continued success. Here, I’ll highlight three avenues that I think will be contributing factors.

“La Bibliothèque Michael McDowell”

Traditionally in the publishing world, each marketing campaign tends to be designed and run in isolation. Not only do publishers universally avoid referencing their competitors' rosters, they also abstain from mentioning similar books from their own back catalogs, even when pointing out such similarities could help get the sales of a new release off the ground. Each book is treated as a product of its own both creatively and commercially, with its own distinct identity, marketing, and business goals.

The one exception to that rule is, of course, when the same author publishes a new book. In that instance, a publisher can safely build off readers' brand awareness to generate anticipation and ultimately sales for "the latest [Insert famous author's name]." Success's compounding effect is undeniable here. The Harlan Cobens and Elena Ferrantes of this world receive premium visibility across out-of-home advertising, earned media, and bookstores, which vastly improves their odds in the marketplace. The longer the streak of success, the more appealing the prospects, the more incentives every stakeholder in the industry — publishers, distributors, booksellers — has to promote an author's next book.

That is the enviable position that Monsieur Toussaint Louverture finds itself in at this time. As mentioned, Blackwater wasn't just a sweeping commercial success, it was also the start of what is now a dedicated collection, “La Bibliothèque Michael McDowell.” It’s hard to say now how serendipitous the initiative truly was: did Monsieur Toussaint Louverture come up with the idea only after seeing the success of Blackwater, or was it all planned from day one? In any case, the saga has laid out a solid foundation on which the company can now base all future marketing efforts.

It’s been making the most of it. Out-of-home advertising for Gilded Needles (Les Aiguilles d'Or) emphasized both the author's name and the richly adorned cover reminiscent of Blackwater. (The illustration for the new book was made by the same artist.) For Blue Moon Over Babylon, the team had the opportunity to name not just Blackwater but also Beetlejuice, piggybacking on the synchronous release of Tim Burton’s movie. This, of course, is a perfect case of eventization, one of the five strategic pillars I recommended publishers embrace. Finally, the same benefits apply online. While doing research for this piece, I was also repeatedly targeted with ads for Gilded Needles on both X and Instagram. Though anecdotal, this alone is proof that the company has been savvy enough to market the book specifically to Blackwater readers, which I don't think is such a common practice despite its obvious potential.

These efforts are also being bolstered externally, as every new McDowell release is now covered across mainstream media. As Monsieur Toussaint Louverture continues to add to the magnum opus of the "Bibliothèque McDowell," brand awareness will only grow, making reengaging readers easier with every new release.

Operationally, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture is also at an advantage in that all the novels in the ongoing McDowell collection came out a long time ago. The texts may still need to be translated, the illustrations designed, the copies printed and the distribution optimized, but the source material is readily available for the team to exploit. In that way, it can take a long-term view and conceive its marketing holistically from the start to develop and maintain consistency across all releases. This kind of visibility is more than most publishers can ever hope for working with more contemporary authors, whose own writing cadence will often force a publisher's marketing to operate in a reactive, rather than proactive, mode.

As for Monsieur Toussaint Louverture’s European counterparts, they can simply replicate the publisher’s proven roll-out strategy in their own markets. Tellingly, Neri Pozza, Blackie Books, and Penguin are all using Oyarbide’s original design, simply translating it to their native languages.

Objects of Desire

In Part III, I pointed to merchandising as an opportunity for publishers to grow and monetize affinity around their IP. Unsurprisingly, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture is one of the few houses to have fully embraced that potential.

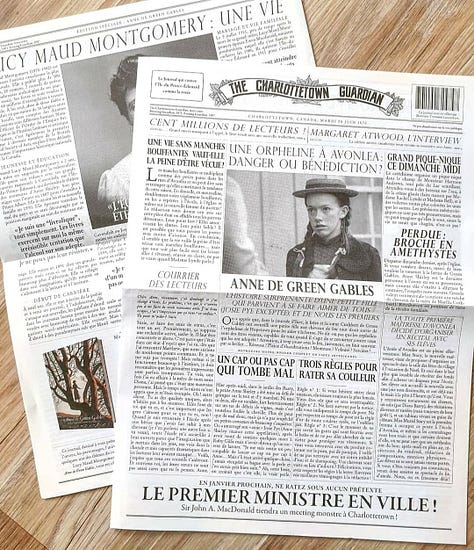

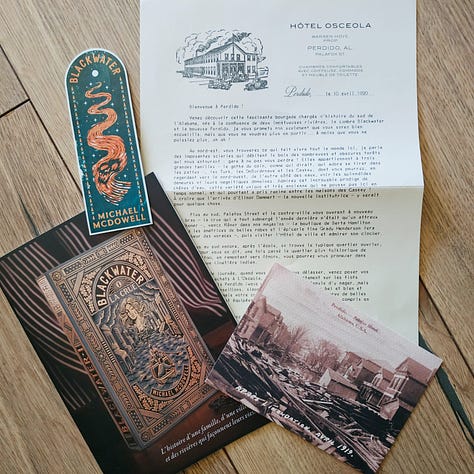

Like others, the publishers started selling merch based on several of its books. For Anne of Green Gables, prints of the covers' original illustrations, along with bookmarks, brooches, and a tote bag. For Blackwater, a "Blackwater Fishing Club" tin mug and a tee-shirt. Ornate cases, packed with exclusive goodies, are also available for readers of both series who would like to put the finishing touch to their sets.

Though limited in range, the collection has been well received. For this first experiment, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture notably bet on IP that, based on book sales and reviews, it knew had an existing fanbase eager to extend the reading experience through whatever token the publisher had to offer. The bookcases, in particular, were the perfect segue. Not only do they acknowledge the growing trend that is shelf staging, they enable the team to apply to merchandising the same craftsmanship it has displayed in the making of the books themselves. As the company continues to grow its catalog and to learn more about the kind of products that speak most to readers, merch may turn increasingly important a revenue stream.

Further down the line, however, the greater opportunity lies in fostering attachment to the umbrella brand, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture itself. As I’ve mentioned, it's a strategy that has been executed to great success outside the publishing world by A24, the disruptive film distributor turned cultural conglomerate. Now, indie presses like Zando are applying the same playbook to books and trying to turn themselves into full-fledged lifestyle brands. With its highly recognizable name, eclectic and singular editorial stance, and direct connection with fans, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture appears uniquely equipped to make the most of this opportunity.

Experiential Everything

Last week, I pointed out the power of experiential storytelling for bringing IP to life. In my view, book publishers should do everything in their power to prolong and heighten readers’ attachment to the stories, places, and characters in their favorite books. And if there’s one rule of immersion, it’s this: Don’t break it. From a book’s cover to its packaging — we’re in the ecommerce era after all — to how and where it’s marketed, every aspect of the experience should be part of a greater narrative and injected with the book’s lore.

Monsieur Toussaint Louverture understands and applies these principles perfectly. Says Bordes: “A book is not just something physical or literary: it’s an economy, a way of thinking, of speaking, an environment, a Wikipedia page, a website, tweets, repetition, reviews…” Accordingly, along with fully-fledged merch, the company has been using various items to promote its roster to early readers and professionals alike. Its translation of Anne of Green Gables came with a 19th century-like newspaper, the fictional Charlottetown Guardian; Blackwater, with postal cards and a letter from the books’ Osceola Hotel. For Katie, it was a business card selling the services of a “medium extraordinaire.”

Thoughtful items are a book’s dream companions, providing memorable and collectable new touchpoints for engagement. At their best, they’re conversational: an opportunity for readers to picture themselves as not as the targets of a clever marketing stunt, but as the participants in an ongoing multimedia experience.

Following the Vision

In a publishing landscape too often defined by the relentless pursuit of the next big trend, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture offers a refreshing alternative. This small indie publisher has carved out a space for itself not by chasing the whims of the market, but by stubbornly staying true to its founder’s taste and vision.

From its eclectic catalog to its beautifully designed books, the company has shown that passion, innovation, and a willingness to take risks can be the keys to success. Blackwater is a testament to this bold approach. By doubling down on craft and reviving the lost art of serialization, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture has not only found commercial success but has also built a devoted following of readers who are now eager to dive deeper into the worlds it creates.

As the "Bibliothèque Michael McDowell" continues to grow, Monsieur Toussaint Louverture can take on its next challenges from what is undeniably a position of strength. It’s living proof that there are still experiments to be run, and fun to be had, in the world of publishing.

That’s it for Part IV — and this series! I hope you enjoyed the journey.

Thank you for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this essay, please consider giving it a like and take a minute to share it with others. It really helps.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts! You can find me on X, or just reply to this email.

Thanks to Jimmy for reviewing a draft of this piece.